Good Shepherd sisters and mission partners in Melbourne, Australia, attended this smoking ceremony during 2022's National Reconciliation Week. The ceremony, a ritual welcoming people to their land, was led by local Indigenous elder Ash Dargan. (Courtesy of Caroline Price)

We asked this month's panel to reflect on the following question:

How are healing and forgiveness facilitated or happening in our communities?

Their answers reflected their congregational charisms and dealt with forgiveness on the individual level as well as important contemporary problems, including migration and Indigenous/First Nations reparations in several countries.

______

Caroline Price from New Zealand is a member of the Good Shepherd Sisters in Melbourne, Australia. Before entering the community, she served with the Royal New Zealand Air Force for 12 years in administration and flight operations. Since making final vows in 1990, she has ministered in New Zealand and in Rome at the Good Shepherd Generalate. She established the congregation's International Secretariat for Justice and Peace, which worked closely with their International NGO Office at the United Nations, and has served as area community leader for the sisters in Victoria, Australia. Currently, she is a member of the province leadership team.

This month in Australia, the 15th anniversary of an apology to the stolen generations of First Nations peoples was remembered and acknowledged in the federal Parliament. On Feb. 13, 2008, then-Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offered a sincere apology to First Nations people across the country for the impact of colonial policies and procedures that disrupted their communities and families for generations. In the apology, he says "sorry" many times for the ways that First Nations people had been marginalized and treated by successive governments. Apologizing is a first step to healing for those involved on both sides.

Indigenous elder Ash Dargan plays the didgeridoo, a sacred instrument, during a National Reconciliation Week ceremony in 2022. (Courtesy of Caroline Price)

But he knew this was not enough. In his speech, he relates meeting with an Aboriginal woman and mother and how he took the time to sit with her and listen. It's a searing, deeply moving story. As he left, the woman told one of his staff that he should not be too hard on the person she spoke of (a stockman on the land) who had hunted children down many years ago. Decades later, that person visited her and apologized. She forgave him for the hurt and anguish caused to her people and her family. She forgave him.

This story highlights the healing for the woman and the stockman. And the prime minister! An apology is a step on the journey to forgiveness and healing that calls for insight into myself and into the community to which I belong and humility in acting to address the hurt and pain suffered by another. The next step — to forgiveness — takes courage, humility, openness of heart and a deep compassion for the other.

There is, in my opinion, a third step: a resolve that impels us to examine and address the wrongs and move to a place of reconciliation and peace. Within the Good Shepherd community, we offer an "Acknowledgement to Country" before each meeting to acknowledge the hurt, and we resolve to work toward reconciliation and peace. Each year, we participate in the activities of the week for reconciliation, working and walking together in a spirit of reconciliation. We grow in understanding as we make this journey together. Good Shepherd also supports any initiatives that foster reconciliation with First Nations peoples. This message is important:

For the future we take heart; resolving that this new page in the history of our great continent can now be written. ... A future based on mutual respect, mutual resolve and mutual responsibility. (Apology to the stolen generations, 2008)

How we heal may be contained within the steps to healing. Generations of pain and suffering are debilitating and entrenching; learning to apologize, and learning to forgive can bring healing, hope, life.

The Lesotho Communication Committee gathers to pray for the peace for the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Lesotho Province. (Courtesy of Lydia Lerato Rankoti)

Lydia Lerato Rankoti is a member of the congregation of Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from Lesotho Province. She is a second-year novice who joined right after high school in 2020. She presently works at Maryland High School as the bursar.

Back in the early days of our congregation, sisters were able to live in deep peace, true joy and tranquility, even in the midst of some major problems. Our congregational foundress, Blessed Mother Marie-Rose, said that trials and difficulties are a part of every life, and it is so important to maintain interior peace, pray for wisdom and place our trust in God.

Today in the 21st century, we try to imitate them and live by the spirit of Marie-Rose while staying open to the signs of times. In my congregation, we have a saying: "We are Marie-Rose yesterday, we are Marie-Rose today," which is why we try to forgive one another in community. One day, I am angry and can't hold on, but my community helps me. The next day, somebody else is despairing, and we say, "You hold on." We need to be together this way; community is formed because of such weakness. We need each other each moment.

Community itself has some scars, growing out of things that accumulate due to our different personalities. We need to deal with them every day; for this, we need deep self-introspection and should change things that don't foster community or that break it apart. We come to community to serve the sick, but we soon discover that we are the sickest and need healing and forgiveness daily.

Sr. Lydia Lerato Rankoti (center) is pictured with her formator, Sr. Ernestina Selialia (left) and Sr. Cecilia Matheso. (Courtesy of Lydia Lerato Rankoti)

In my community, we meet individually with the superior to discuss challenges and health of the community. We make retreat on at least one weekend a month. This brings us together and opens our hearts to know that it is Jesus who calls us. I love the proverb: "There is no rose without a thorn." It reminds me that we have to come together despite our difficult personalities and be one as the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are one.

Thus, we are able to forgive and heal. If I weren't in community, who would tell me that it's all right, that there is a God who loves me the way I am? Or who would tell me that I don't have to flounder around, not knowing what to do, but that I can reach out to others?

In the end, we are here — looking at each other and listening to each other's stories — to make our living beautiful and attractive, as Pope Francis invites us to make the church attractive.

Notre Dame Srs. Claire Gervais (left) Silvia Leticia Corea Sagastume chat in this 2013 photo. (Courtesy of Congregation of Notre Dame)

Maco Cassetta is a member of the Congregation of Notre Dame. She is a part-time licensed psychotherapist working with religious life, formation, resiliency, grief, transition, communication skills, sexuality, inner child work, addictions, PTSD, complicated grief, and reconnection to one's soul self, all within an eco-holistic framework. She also does spiritual direction. In her parish, she is the coordinator of the care of creation team and a member of the liturgical team, planning and facilitating prayer evenings. Presently, she is novice director for her community and lives in White Plains, New York.

Healing and forgiveness are at the core of who I am as a woman religious and a member of the Congregation of Notre Dame. Following the Gospel way is imitating the nonviolent Christ who promotes God's deepest love for humanity.

In today's polarized climate, facilitating healing and forgiveness — creating space for dialogue and understanding — are so necessary. More than ever, we are invited to engage in finding ways to converse, collaborate in solidarity and work toward the healing of our sacred humanity.

I find solace in knowing that our charism of liberating education fosters healing and forgiveness. It encourages us to participate in the work of transformation by creating space that promotes liberation so that every being can live as God intends all to live. Our mission is to participate in the empowerment of the spirit through healing and education. As we engage in the process, we also participate in the transformation of unjust structures that oppress those marginalized in our society. How essential it is today for us to intentionally facilitate such work!

Notre Dame Srs. Bertha Lilian Barrera Ramírez (second to the left) and Cruz Idalia Nieto (second to the in Santa Barbara, Honduras (Courtesy of Congregation of Notre Dame)

The foundress of our congregation, St. Marguerite Bourgeoys, encouraged us to live as the first Christian community did of "one mind and heart." That urges us to adopt attitudes of healing and forgiveness that draw us in an active and inclusive love that is liberating and hope filled. I understand that these attitudes include humility and compassion, unconditional positive regard, and right relationship. It has been our role to promote a climate of acceptance of the gift each one is to the universe, allowing those we encounter to be agents of their own personal transformation and healing.

This relationship of liberation reflects the Gospel story of the Visitation, when at Mary's greeting, the baby leapt in Elizabeth's womb. The encounter of these two women provided the opportunity for the empowerment and liberation of the spirit that is about hope and restoration. Like Mary and Elizabeth, we too are invited to go out in haste and connect with all those that we encounter. We are invited to be open, attentive and receptive of God in others and in ourselves. That is liberating! We are invited to do so in an intentional manner as mutual pilgrims on this visitation journey of transformation and healing so we can birth and build together a just world.

Some of us have been walking closely with migrants who have been on a journey. Participating in their liberation has been gift. How humbling it is to be a witness and participate in their personal transformation. Walking by them has been life changing, healing and hope filled.

Lynn Caton has been a Sister of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, for 16 years. While raising a son, she spent many years in the corporate world, primarily in service and finance, leaving a career as a manager of the accounting department of a Fortune 500 company to enter religious life. Later, she served in prison ministry and as director of a parish outreach program. Her current ministry is as a certified addiction counselor in a hospital, serving women seeking treatment for substance abuse disorder in an inpatient setting.

What was I thinking? My first essay for Global Sisters Report and I'm going to name the shadows of my congregation? Dear sisters, you can exhale; I have no intention of doing so. I will, however, challenge each of us to name, and claim, that which draws us from God personally and as a congregation.

In spiritual language, "this is an examination of conscience." In my ministry in Alcoholics Anonymous, it's called the fourth step: "made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves." Either phrase demands a mature self-reflection for healing and forgiveness.

Personally, I think AA's fourth step is more transformative than the spiritual language. Perhaps those with substance use disorders believe they need more forgiveness. Even Scripture tells us those who have been forgiven more are closer to God (Luke 7:40-47), so the short answer is forgiveness is necessary to be closer to God.

Several religious congregations in North America have recently begun seeking healing and reconciliation for the sins of slavery and cultural genocide. My particular congregation was founded in New York in 1856, long after the land was taken from the Lenape, Pequot, Narragansett and Shinnecock Indigenous nations.

We live on land that was stolen and has become one of the most segregated regions in our country. For decades, we taught in inner cities; we had sisters march in Selma, Alabama; we're allied with Shinnecock women to help heal the earth. Currently, a sister brings food and clothing to migrants being bused to the Port Authority in New York City.

Sr. Mary Antona Ebo, a Franciscan Sister of Mary, is pictured in the front row at the center with her superior, Sr. Eugene Marie Smith, as they march in Selma, Ala., March 10, 1965, to support voting rights for Blacks. (CNS file photo from the St. Louis Review)

We have an expression: "Where one sister is, there is the congregation." We are all there — at Selma, at the Port Authority. The shadow is also true. When any one of us fails to see, hear or speak out, we are there and need to seek forgiveness. We must have a clear understanding of the hurt we have caused. At our most recent chapter, we made a commitment for this type of reflection. We identified our desire to work toward healing the evils of our society.

We're first challenged to commit to address our own role and/or biases against our dear neighbor. Our 2021 chapter direction statements included the phrase: "We acknowledge the culpability of our own biases and our participation in oppressive social, political and religious policies and practices. In response to the sin of racism and other evils, we pledge to ourselves to undergo personal and communal transformation." We are beginning the difficult task of a "searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves" as a means of healing and forgiveness for us individually, for our congregation and for our dear neighbor.

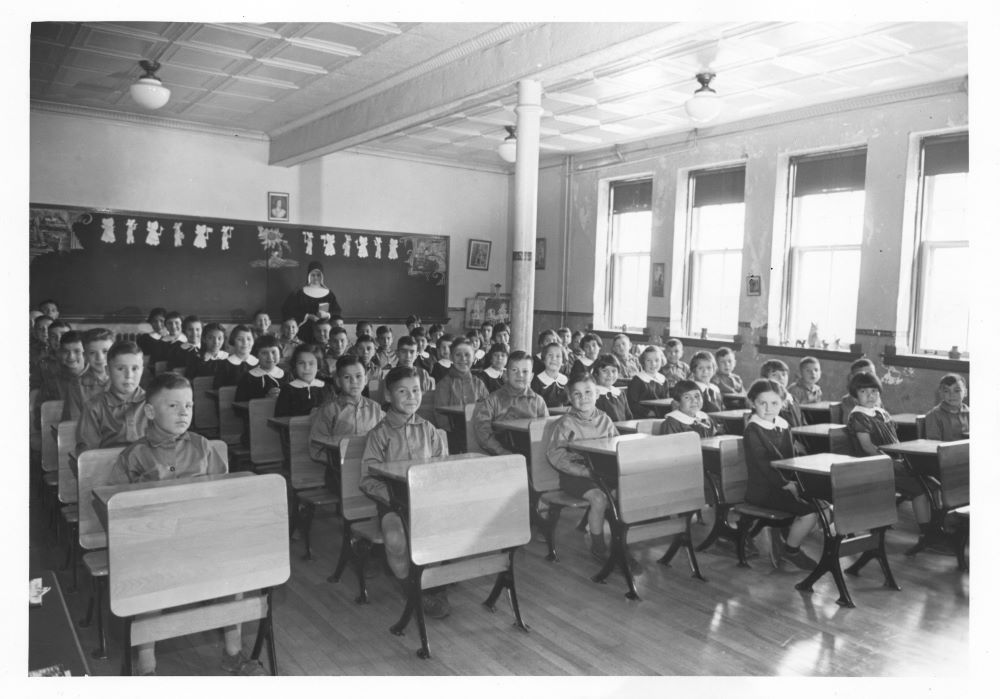

A nun stands at the back of a classroom at the Shubenacadie Residential School in this 1930s photo. The school operated 1929 to 1967. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Charity of Halifax)

Nuala Patricia Kenny is a native New Yorker and a Sister of Charity of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. She is a physician, pediatrician, and bioethicist, practicing, teaching, and working at several hospitals in Canada and receiving many honors for her work in child health, medical education and health policy. Past president of both the Canadian Paediatric Society and the Canadian Bioethics Society, she was chair of the Values Committee of the 1997 Prime Minister of Canada's National Forum on Health. She has authored numerous papers and several books. ([email protected] – has art)

As a pediatrician, I have learned that healing from serious illness and trauma requires recognition of need, a correct diagnosis, an effective treatment, a cooperative patient and a supportive environment.

The May 2021 heartbreaking discovery of 215 unmarked graves of Indigenous children at a former residential school in British Columbia, Canada, presents an urgent need for healing. My religious community, the Sisters of Charity of Halifax, taught in residential schools in Nova Scotia and British Columbia and has been struggling to understand our complicity.

All abuse of vulnerable persons — physical, psychological, spiritual, cultural and sexual — is abuse of power, position and trust. Diagnosing underlying religious, political and cultural factors fostering abuse is essential.

These schools were a component of Canadian Prime Minister John MacDonald's assimilation policy to solve "the Indian problem" and open lands to white settlers. From the 1870s to 1996, 150,000 children were forcibly removed from their homes and families to "take the Indian out of the child." They experienced forced conversion to Christianity and suppression of Indigenous language, culture and spirituality. Over time, Canada operated 139 schools as a "joint venture" with Anglicans, Presbyterians, United Church and Catholics. Similar programs operated in the United States and Australia.

Healing for residents will be a long process because the harms occurred during the crucial time of child development. We need conversion of minds and hearts to the belief that we are all children of the Creator God in one human family. We must also provide support to survivors with financial settlements, grants, scholarships and joint projects.

Advertisement

The cooperation of survivors, Indigenous and church leaders, and politicians is needed to overcome denial of racism and continue the progress we have made creating an environment supportive of healing and reparation including:

On his "penitential pilgrimage" to Canada in August 2022, Pope Francis asked forgiveness "for the church and Religious communities cooperation ... in projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation promoted by the governments of that time."

Between 2007 and 2015, the Canadian government provided $72 million in restitution in the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission's final report in 2015 contained 94 calls to action. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation continues education and advocacy.

The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops committed $30 million for an Indigenous Reconciliation Fund and has promised to address ongoing systemic injustices.

My congregation has listened to survivors, acknowledged their suffering and apologized. We have understood education as liberating and opening doors, especially for the poor. We now know to our sorrow that residential schools were racist and oppressive. Tragically, we now understand the evil and contradiction of forced conversion to a loving God. We are committed to walk humbly with our Indigenous sisters and brothers as we work for healing and reconciliation.