Sr. Maritze Torres explains the "triptica," a mural taking viewers through Trujillo's bloody past (on the right), to its present marked with struggles for justice (center), to its hopeful future, filled with abundance, education, good health and good fortune. (Tracy L. Barnett)

In a homey third-story apartment in Soacha, Colombia, on the outskirts of Bogotá, Sr. Maritze Trigos Torres pulls a plastic bag from a cabinet. Inside are photographs no one should have to see: the decomposing body of Fr. Tiberio Fernández Mafla, found without head or hands in the Cauca River; a mother cradling the skull of her disappeared child; a charcoal death threat scrawled on a wall with Trigos' name on it.

"Se van o los picamos, defensores de mierda," the message reads. "Leave or we'll cut you up, defenders of (expletive)."

At 82, this diminutive Dominican nun — barely five feet tall with a crown of snow-white hair — has spent more than half a century defending human rights, weathering death threats like this one. What she has lived defies characterization, but she has made a life of putting words to the horrors she has witnessed — as a poet, an activist, a public speaker and an organizer.

She had recently suffered a stroke, she said, which explained the quaver in the firm and eloquent voice that had denounced the crime and corruption and horror that have plagued these lands for half a century.

Yet nothing has dimmed her radiant smile, which alternates with fierce denunciations of the powerful forces that have terrorized Colombia's poor. She has witnessed their cruelty far too often in her work with victims of the country's decades-long armed conflict.

"When I arrived, people couldn't speak," Trigos said. "The trauma was so deep. Mothers who had seen their children tortured became mute."

She speaks truth to power as readily as she flashes her mischievous grin. "Soy la monja rebelde," she likes to say — "I'm the rebel nun." Indeed, she has challenged authority since she joined the congregation at 18 in 1961 with the Dominican Sisters of the Presentation, the order that educated her as a child in Ocaña, north of Santander. She took her religious vows in France, in 1964.

"Resistir, persistir y nunca desistir (Resist, persist, and never give up)," she said, reciting the motto of AFAVIT, the Association of Family Members of Victims of Trujillo — a picturesque town in the Valle del Cauca that has become a symbol of the country's collective memory and reckoning with past atrocities.

For decades, Trigos has lived and worked in the toughest barrios that ring the capital of Bogotá; the past 23 years of it with her longtime companion, Sr. Teresita Cano. Here they run the "El Pueblo" Hogar Comunitario (Community House), a three-story building in the southern municipality of Soacha that has served as a school and a refuge for at-risk neighbor children, and a dormitory and workshop space for victims and human rights activists alike.

Besides the daily activities that the sisters organize in the Seeds of Life school and the Community House, once a month, they load up their grey Chevy Aveo with their driver, Guillermo Sanchez, and make their way nine hours south over the rugged backbone of Colombia to Trujillo. There, they have been carrying on the work of accompanying and supporting the victims of the violence for 30 years in a multitude of ways.

The Trujillo Massacres: When terror came to town

Between 1988 and 1994, an estimated 342 people in the region around Trujillo had been tortured, dismembered or forcibly disappeared in a wave of violence perpetrated by an alliance of paramilitaries, military and drug traffickers. Much of this terror was unleashed in response to the social work of Fr. Tiberio Fernández Mafla, a diocesan priest who was appointed parish pastor in Trujillo in September 1985.

Fernández became a heroic figure, promoting economic development through the formation of cooperatives in the abandoned region, helping establish 24 community enterprises like bakeries, carpentry businesses and coffee-growers' associations. These cooperatives were designed to empower marginalized peasants — especially women — and counteract the influence of paramilitaries, guerrilla forces and narcotraffickers and lift his flock from poverty.

Cabinetmakers (ebanistas), drivers and coffee harvesters were among the groups targeted in the massacre of members of the cooperatives organized by Fr. Tiberio Fernández Mafla, memorialized in this handmade detail in the Monument Park. (Tracy L. Barnett)

But his efforts to organize the poor and demand their rights to health and education quickly drew the ire of powerful interests. The cooperatives were branded as guerrilla collaborators, even as the groups pursued peaceful economic self-determination. Fernández began receiving death threats, and was repeatedly warned to abandon his work or leave town. Undeterred, he continued to speak out against injustice from the pulpit and in the streets.

"If my blood contributes so that peace may dawn and flourish in Trujillo, I will gladly shed it," Fernández prophetically proclaimed in his final Good Friday sermon.

Three days later, on April 17, 1990, he disappeared, along with his niece Alba Isabel Giraldo and two others. Four days later, they found only the body of Fernández, beheaded, castrated, without hands and brutally tortured.

The priest's murder was meant to silence Trujillo forever. Instead, it became the catalyst for one of Latin America's most extraordinary grassroots memory projects. While Jesuit Fr. Javier Giraldo played a pivotal role in launching the effort — documenting testimonies and mobilizing families through the Inter-Church Justice and Peace Commission — it was Trigos, together with Cano, who became its enduring presence and moral anchor. The duo supported the legal process led by the José Alvear Restrepo Lawyers' Collective in achieving convictions of those responsible: drug traffickers Henry Loayza and Diego Montoya, and military officers Major Alirio Urueña and Lieutenant Fernando Berrío.

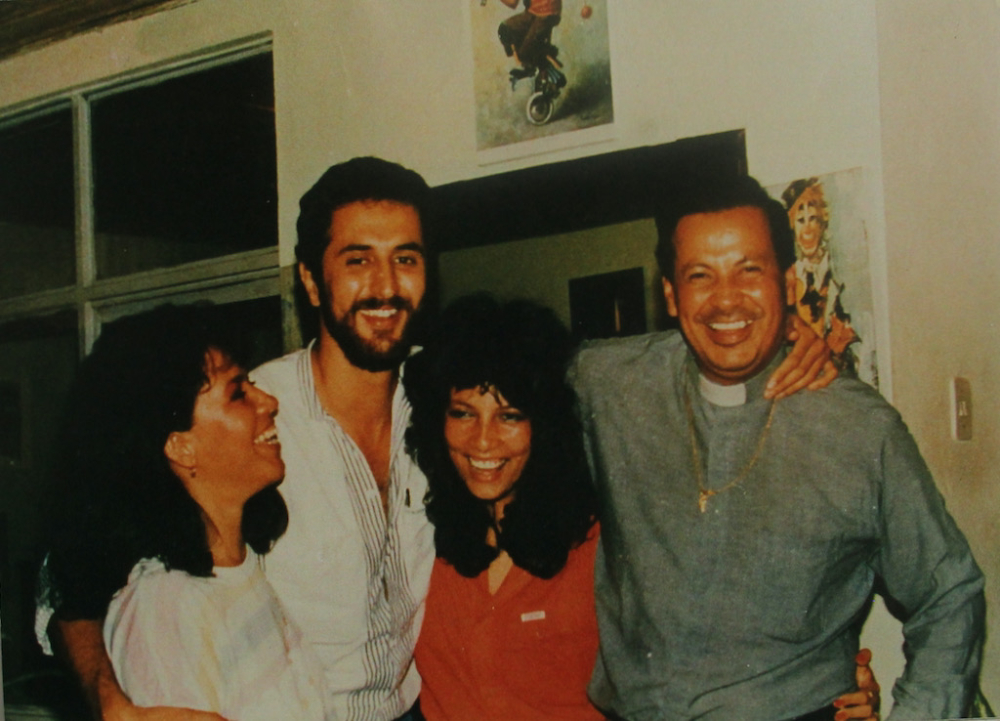

From the right to left, Fr. Tiberio Fernández Mafla, his niece Alba Isabel Giraldo, and architect Oscar Pulido, all of them killed in the Trujillo massacre. On the far left is Idalia Giraldo, sister of Alba Isabel, who was able to escape to Spain as a refugee. (Courtesy Maritze Trigos Torres)

From the University of Paris to the slums: A liberation journey

Trigos' journey toward liberation theology began not in Colombia but in France, where she was studying during the Second Vatican Council. When she finally returned to Colombia, she chose to live among the people, immersing herself in their struggles, rather than simply ministering from a distance. Trigos' decision met fierce resistance from her superiors, but she persisted.

"I didn't join a religious order to live in a convent," she told Global Sisters Report, first settling in the working-class neighborhood of El Diamante in Bucaramanga, where her activism and solidarity with students and laborers soon drew the suspicion of church and state alike. After several years and mounting pressure, she moved to Bogotá in 1974, working with street children in the city center and later in the marginalized neighborhood of La Paz, on the slopes of Monserrate.

There, living side by side with families surviving on the edge, Trigos and her companions deepened their commitment to a faith rooted in justice and community. This hands-on ministry would soon carry her to Soacha, a rapidly growing municipality on the city's outskirts, where waves of displaced families — many fleeing armed conflict in regions like Chocó, Cauca, and the Magdalena Medio — were settling in precarious conditions. There she and Sr. Isabel Sarmiento opened the first hogar comunitario for displaced children. Soon they were joined by Cano, who has remained a rock for Trigos and the community they serve.

Trigos' decisions prompted tension with her Dominican superiors, and several times she was expelled from the order. When she later rejoined, it was with a firm insistence that her vows include this grassroots accompaniment. The experience became the spiritual and political foundation for the work that would define the rest of her life.

Advertisement

The transformation from working with street children to accompanying massacre survivors was a natural evolution of Trigos' commitment to Colombia's most vulnerable. In 1995, news reached her of an extraordinary victory: the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had just reached a landmark "friendly settlement" with the Colombian government over the Trujillo massacres, marking one of the first times Colombia was held internationally accountable for state violence.

Giraldo had spent years quietly gathering testimonies from terrified families, eventually compiling over 100 cases to present to the commission. His efforts, supported by the Inter-Church Justice and Peace Commission, resulted in promises of reparations and the construction of the Monument Park for Memory.

Turning grief into memory

Trigos arrived in Trujillo more than three decades ago, when the town was still reeling from years of horrifying violence. From the beginning, she helped design the memorial park, accompanied exhumations of the victims' remains and led healing rituals with survivors. While Giraldo brought institutional support from Bogotá, Trigos moved to the region and remained embedded in the community, turning individual grief into collective resistance through three decades of unbroken accompaniment.

"When I arrived, people couldn't speak," she said. "The trauma was so deep. Mothers who had seen their children tortured became mute."

Trigos began with the simplest act: listening. With Cano, she traveled rutted mountain roads to remote villages, sitting with families as they slowly found words for their losses.

"The first grief work we did as families, because we didn't talk, was making sculptures of our children," said Ludibia Vanegas, AFAVIT's current president, who lost her 18-year-old son.

Sr. Maritze creates an altar from photos of Trujillo's many victims, with a banner proclaiming "Justice" and "Life" emblazoned on a map and flag of Colombia. (Tracy L. Barnett)

This became Trigos' method: transforming pain into tangible memory. Working with artist Adriana Lalinde from Medellín, families molded representations of their loved ones engaged in life's work — a taxi driver gripping his wheel, a midwife with outstretched hands, a coffee picker with his basket. Today, 235 bas-relief sculptures line seven levels of ossuaries climbing the hillside above Trujillo.

"I didn't even know what memory was," said Ludibia, now 72. A campesina who began delivering babies at age 17, she embodies the transformation Trigos facilitated — from isolated grief to collective action.

The project expanded organically. Families began writing about their loved ones, bringing photographs, sharing stories. When organizers asked for memories of Fernández in 2003, the handwritten testimonies were turned into a book later recognized by UNESCO: Tiberio Lives Today: Testimonies of the Life of a Martyr.

"I felt such joy in my heart," Ludibia said of seeing her simple words honored internationally.

When remembering becomes resistance

But memory work in Colombia is dangerous. The death threats against Trigos intensified after 2010, when AFAVIT began pushing for prosecutions. One morning in 2013, paramilitaries came to her door in Trujillo demanding Cano hand over Trigos.

Trigos recalled a man approaching her with a gun in Monument Park. She took his face in her hands, looked him in the eye, and said softly, "What are you looking for? What do you want?" He turned and walked away.

"Dios mío, My God," Cano recalled thinking, her eyes widening at the memory. She didn't know if they would take her instead.

Thankfully, they went away. But another time, Trigos recalled a man approaching with a gun in Monument Park. She took his face in her hands, looked him in the eye, and said softly, "What are you looking for? What do you want?" He turned and walked away.

Trujillo Mayor José Luis Duque was less subtle in his opposition. "Shut up, sister," he ordered her in front of the Ministry of Justice. "That happened many years ago."

Trigos' response was equally direct: "Forgive me, but you are very ignorant," she said. "Go to Europe and see the memorial sites. Recovering memory is a right of the victims, and very meaningful."

Murals throughout the complex depict Father Tiberio Fernández Mafla, the AFAVIT youth musical ensemble, and hopeful images depicting the healing process. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Today, Trujillo's impressive Monument Park has become precisely what she envisioned — Colombia's most significant grassroots memorial to state violence. The six-hectare site includes not just the ossuaries but a mausoleum for Fernández, a gallery of Martyrs of Faith, a Gallery of Memory that also serves as a gathering space, and the National Memory Path — 14 stations documenting massacres across Colombia and five other Latin American countries. The park is now the destination for pilgrims who come from across the country and around the world, and the guides are family members of the victims, working to heal the wounds and keep the war from fading into oblivion.

Cano moves through Monument Park with the quiet authority of someone who has tended to it with her own hands and heart, guiding visitors past Fernández's watchful image and along the sunny paths where memory takes root. Together with Trigos, she has helped shape this sanctuary, narrating the stories behind each handmade sculpture, and honoring the fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers immortalized in clay and cement by grieving families.

As she pauses to touch a favorite heliconia or to recall the life of a victim whose name is fading from a plaque, Cano's presence is both gentle and resolute. "Here, the wounds of violence are transformed — through remembrance, through care — into seeds of hope," she said.

Sr. Teresita Cano points out the bas relief sculpture of Alejandro Betancur, one of 235 that line the walls of the ossuary looking out over Trujillo from the Monument Park for Memory. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Nelson Fernández, a Trujillo native and AFAVIT vice president who lost his brother to the violence, credits Trigos with maintaining the community's resolve: "Maritze has maintained this place; without a doubt, it's here because of her."

Trigos has also become one of Colombia's most recognized poets of memory. Her latest collection, "Huellas de Vida y Esperanza" ("Footprints of Life and Hope"), contains over 100 poems drawn from decades of accompanying victims. She writes not as an observer but as a witness who has absorbed others' pain into her own body.

The next generation of AFAVIT

As the founders and matriarchs of AFAVIT look toward the future, a new generation has stepped forward to carry the torch of memory and resistance in Trujillo. Among them is Robinson Andrés Montes Arciniegas, a young teacher whose family's roots in the community run deep. This year, he's begun the work of reactivating the youth group affiliated with the organization, he said, discussing the challenges of engaging young people in the work of historical memory, social reconstruction and healing.

"The current youth of Trujillo are sometimes apathetic about the topic of historical memory," he said. "That's why we are rebuilding the youth group: so they know what happened, so it's not repeated."

Luz Marina Betancur and Robinson Andrés Montes represent the future of Trujillo. The mural behind them reads, "Remember: from the Latin recorderis, which means to pass through the heart again. — Eduardo Galeano" (Tracy L. Barnett)

For Robinson, the legacy of Fr. Tiberio Fernández Mafla and the pain of the past are not distant history, but a call to action.

"We have to maintain this historical memory, remembering our people who are gone ... to maintain the dignity of the victims and of the municipality itself," he said. "We have to work on social reconstruction, but everything starts with memory."

Alongside him is Luz Marina Betancur, who grew up in the shadow of the massacre and was shaped by the early years of AFAVIT's work. From childhood, she and her peers were drawn into the association's activities, forming the first youth groups under the guidance of Trigos, and later returning as professionals to strengthen the organization. Now serving as secretary and treasurer of the Monument Park, Betancur is at the heart of AFAVIT's operations — coordinating projects, guiding visitors and mentoring the next wave of leaders.

"We need this generational handoff from the adults, and now that we're graduating from university, that work continues — combining the experience of more than 30 years," she said.

From shattered pieces, new life

As the visit to Trujillo drew to a close, Trigos organized a small ceremony in the Gallery of Memory. At the center of the room, an altar had been arranged with faces of the fallen and a brightly colored map stitched with the words JUSTICE and LIFE. A circle of survivors, descendants and young musicians from the AFAVIT Youth Group sat quietly as the lights dimmed and the image of a broken clay vessel appeared on the screen, echoing the prophet Jeremiah's promise that what is shattered can be remade.

Sr. Maritze speaks to the AFAVIT Youth Ensemble and members of AFAVIT in a moving ceremony for memory and life. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Trigos gestured to the clay shards and explained that Trujillo itself was the vessel — cracked by war, yet stubbornly being pieced together by its people.

Trigos lifted a single candle from the altar, its flame trembling in the dim light. "We are the broken vessel," she said, "but we are not lost. In each fragment lives memory, and in each memory, the seed of new life."

One by one, members of the circle stood to voice proclamations of resistance and hope, their words braided together by music and memory. The candle passed from hand to hand, illuminating faces and stories, until it returned to Trigos — its light a quiet promise that Trujillo's circle of memory and hope would endure: "Resist, persist and never desist."