Sr. Karen Burke, left, and Sr. Annelle Fitzpatrick, center, are flanked by refugees the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood in Brentwood, New York, have welcomed onto their campus. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Editor's note: The yearlong GSR series "Hope Amid Turmoil: Sisters in Conflict Areas" has focused on sisters' ministries serving those who live in areas affected by war and civil conflict. Today's piece takes a different angle: examining a sisters' ministry on Long Island, New York, which is helping refugees who have arrived in the United States from conflict-affected countries like Afghanistan and Ukraine. Publishing the story this month is appropriate — Sept. 24 is the church's annual World Day of Migrants and Refugees.

The answer was an affirmative yes.

With Afghanistan's fall to the Taliban in August 2021, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, were asked by contacts on Long Island's interfaith community if "the nuns" had any extra space on their campus to house incoming refugees.

The sisters said they did. So, in December 2021, the doors of the congregation's large campus on central Long Island opened — and "opened wide" as several sisters say — and have remained so for nearly two years now.

What began as a small initiative to welcome a few refugees has now become a growing and sustained program that has housed 23 adults and 16 children from three countries — Afghanistan, Pakistan and Ukraine — on a large 211-acre campus with more than a dozen buildings.

Three buildings — including a small wing of an older dormitory-style building and several smaller residential houses — are accommodating the arrivals, who have been accepted through a number of agencies, including Catholic Charities, Women for Afghan Women and a Ukrainian initiative of Lutheran Social Services of New York.

"We have space and resources," said Sr. Tesa Fitzgerald, the congregation's president. "It's a sin not to do it."

"It's the humane thing to do," said Sr. Annelle Fitzpatrick, who directs the program. "Jesus would be the first to open the door and say, 'Welcome.' "

She added: "It's brought new life to these old walls," saying that what the congregation is doing is making concrete its charism "That all might be one," and that it is important to respond "to the needs of our times."

A Ukrainian flag flies outside a house on the campus of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, where two Ukrainian families resided. The house now flies an Afghanistan flag in front where Afghan families live, along with Srs. Karen Burke and Clara Santoro. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

The 293-member congregation was unanimous in its welcome. "Not a single sister has said anything negative about this. That's a miracle," Fitzpatrick said.

The needs are concrete — whether it be helping find jobs for the new arrivals or determining, because of immigration status, who can or cannot receive public benefits.

In evaluating the program's first year, Sr. Karen Burke said that the congregation was prepared for the many attendant challenges in welcoming the refugees — be they "overcoming language barriers, securing health insurance, applying for [public assistance] SNAP benefits, enrolling kids in school, or dealing with issues of depression and post-traumatic syndrome."

What the sisters were not prepared for, she said, was "how labor intensive the ministry to displaced families would become."

The layers are many and complex.

"The time involved in taking refugees to interviews, medical appointments, enrolling children in school, and attending immigration hearings is incredibly time-consuming," Burke said.

Igor Konovalova, Sr. Karen Burke and Igor's wife, Anna, outside the home where the couple lives with another Ukrainian family. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

That is why it has been necessary to hire a part-time case manager to help the program director in day-to-day work — work that Burke believes will only expand if more arrivals are welcomed to the campus.

In addition to housing refugees, providing vocational training and courses in English as a second language, the Brentwood sisters also host the Long Island Immigration Clinic on their campus, a center where sisters and community volunteers counsel immigrants on asylum claims, assist in finding legal assistance and prepare the arrivals for court appearance and immigration interviews.

In taking a strong "pro-immigrant" stance, Burke believes that the congregation is taking a principled position that can serve as a practical example to other sister communities wanting to do the same.

"Other congregations have asked, 'How do you start this?' How can we do what you're doing?' " she said. There is not one single answer to that, though Burke said two things help: One is having available space. The other is being located in a larger community which has a history of welcoming immigrants.

Once a predominately white enclave, the city of Brentwood — with a population of about 62,000 — is now 73.5% Hispanic or Latino, according to census data. "We're in an immigrant community," Burke said, "and that's made it easier for us to do our work. They are very supportive."

Arrivals feel safe after experience in war-torn areas

In several interviews over the last 10 months, the refugees have expressed relief that, coming from countries such as Afghanistan and Ukraine, they are in a safe place.

They say they are simply happy to be alive.

"I love everything about America," said Hussain Shams, an Afghan refugee who worked as a photographer in Kabul and arrived in the United States in August 2022 and then in Brentwood a month later.

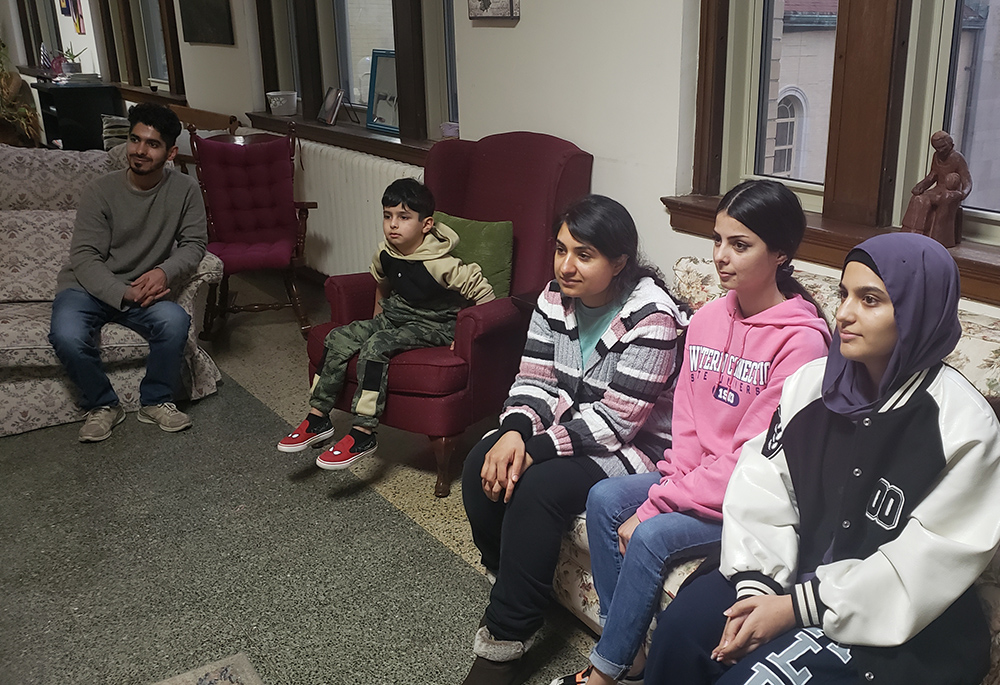

Recent refugees Hussain Shams, Omar Shams, Nadia Khan, Saliha Shams and Tamana Sayed watch TV at their residence on the campus of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood in Brentwood, Long Island, New York. The sisters are offering temporary housing to a number of refugees from at least three countries. Khan is from Pakistan; the others are from Afghanistan. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Shams is now employed as a painter and carpenter on the Brentwood campus and would like to become a skilled maintenance man. He continues his English education, as does his wife, Saliha, who was recently hired as an assistant teacher in the universal pre-K program on campus. The couple's sons are enrolled in local schools.

"We have a future here. There isn't hope in Afghanistan now," Saliha said about life under Taliban rule since 2021.

Meanwhile, Tamana Sayed, another Afghan refugee, has received her GED diploma and hopes to attend college. Though she works now on the sisters' large on-campus farm, Sayed would like to get a permanent job off-campus.

Hope for the future also animates the lives of the Ukrainians.

"It's definitely peaceful," said Oleksandr (Alex) Somin, one of the Ukrainian arrivals — and that makes it easier to focus on acquiring work, settling down and having new aspirations. But, he added, immigrants always face challenges. "It's a completely different culture," he said. "Different rules. You have to adjust to the culture."

Recent Ukrainian refugees in January this year at a residence on the campus of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York. On the left, Kseniia (Kate) Kasieieva and her husband, Oleksandr (Alex) Somin, On the right, Anna Konovalova and her two children, son Herman and daughter Diana. Later in the year, in June, Anna and the children were reunited with their father, Igor. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Still, as he eyes doing work in online sales, Somin sees more opportunities in the United States and hence, a more comfortable future.

Even before the war, he said, it was "difficult to get the right job, to get what you want" in Ukraine.

But the war itself has caused him and others to feel that a chapter has turned, perhaps permanently, with people having left Ukraine and friendships in the country now harder to sustain. "We miss Ukraine a lot. We miss our previous life," Somin said. "But I don't think we can rebuild that."

Somin's family lives with two other Ukrainian families in a two-story house on the campus. The newest arrival, in June, was Igor Konovalova, whose wife, Anna, had been living in the United States since June 2022 with the couple's two children, a son aged 5, and a daughter aged 9.

Igor and Anna Konovalova are flanked by their children upon Igor's arrival at John F. Kennedy International Airport in June. (Courtesy of Anna Konovalova)

That was a nerve-wracking year, Anna said, recalling the constant worry about her husband's safety. Igor worked as a commercial director at a bread factory in the central Ukrainian city of Dnipro and had volunteered to work close to the front lines of the war, helping distribute bread — an experience he described "as scary."

Both of the couple's children are attending local schools but the daughter is also doing online learning in Ukrainian. "If you lose your culture, you lose yourself," Anna said.

In an interview just weeks after Igor arrived in the United States, the couple expressed happiness of being reunited but also spoke of the uncertainties ahead of whether to remain in the United States when the war ends or to return to Ukraine, which will eventually need massive reconstruction assistance. Both have family remaining in Ukraine.

"It's our country," Anna said of the experiences of the last 18 months in Ukraine and the dismay and disruption caused by Russia's full-scale invasion. "We had a normal life," she added wistfully.

For now, both are employed — Anna in the high-tech sector and Igor working in the cable business. Of the two, Igor seems more intent on making a go of things in the United States.

"We have an opportunity to live in the U.S, to work, for the children to go to school," he said. "I'm happy with it."

Still, the war is never far from their minds. Though Anna's parents are about 200 miles from the war front, she worries about their safety. As for Igor, he no longer checks the news from Ukraine constantly — once a day is enough, he said.

Anna Konovalova shows a photo from Ukraine on her phone. She is in constant touch with family back in Ukraine. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Challenges in a new country are numerous

The couple's English is good and learning English, of course, is an important element in acquiring the skills needed for success in new lives. Yet English is often not an easy language to learn, especially for adults.

That is part of the immigrant experience that can prove challenging — Fitzpatrick acknowledges that for some of the refugees, especially those who came without much English facility, coming to Long Island is probably not unlike landing on Mars.

Other sisters concur.

"It's a wonderful relationship we [the sisters] have with the refugees, but we know it's a struggle for them in a new country," Burke said.

In a written evaluation of the program, the sisters noted the need for "benchmarks" in evaluating progress for the arrivals but realize that success can mean different things for different persons and families.

Advertisement

"Many refugees suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and a lack of hope," Burke said, who also noted the challenges the refugees faced in even getting to the United States. One family, for example, journeyed from Ukraine to Moldova, then Poland, Turkey and Mexico before arriving in the United States.

For such families, learning English is at the top of priorities, but so are completing vocational training programs and advancing children in school. Also important: establishing a modest savings account and eventually gaining mastery of job skills and, of course, securing a steady job with benefits. And all of these have to be done in complying with federal immigration rules.

Though there is no set timeline, a key goal for the arrivals is to eventually leave the campus and live independently. But for now, all are asked to stay on campus at least one year.

As for cultural and religious differences between the refugees and their hosts, Fitzpatrick said that, particularly in the case of the Afghans, who come from a predominantly Muslim country, the arrivals really "don't know much about nuns."

"But they do know what motivates us," she said, "and they know they are safe."

True enough. Hussain Shams said, "The sisters are really angels."

From left to right, refugees Tamana Sayed and Saliha Shams, both from Afghanistan, and Sr. Annelle Fitzpatrick, director of the refugee resettlement program on the campus of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

But the sisters, too, have had to work around limitations and challenges — none of the sisters speak Ukrainian or any of the languages common in Afghanistan, such as Urdu.

Using translation and online apps on smartphones have helped everyone, though Fitzpatrick said small gestures are always appreciated.

"The shortest distance between two people," she said, "is a smile."

Smiles not only help, they promote the crossing of boundaries, something known by some of the congregation's older members who are tutoring the new arrivals.

"An older nun in a wheelchair is capable of teaching conversational English," Fitzpatrick said. "That gives them a sense of hope and purpose — that they still have something to give."

Something to give. To Fitzpatrick and the other sisters, it's about that and applying the Gospel mandate to welcome the newcomer.

"For me," Fitzpatrick said, "it's front and center of what God asks of us."