Diné elder and adviser to the delegation, Pat McCabe, center, and Providence Sr. Barbara Battista grab hands in celebration and solidarity at the gathering, held July 18-20, in defense of Oak Flat in southeastern Arizona's Tonto National Forest. (Courtesy of Steve Pavey)

With its ancient Emory oaks, canyons and volcanic rock formations, Oak Flat is a place where, in late afternoon, the quiet approach of dusk brings a sense of stillness and serenity, peace and wonder.

This high plateau basin in southeastern Arizona's Tonto National Forest is not only a place of beauty. It is also the site of the Apache creation story: where humans emerged, God touched the Earth, and where the angelic Ga'an still reside, offering their wisdom.

Yet this most sacred of sites — public land that is used as campground and hiking trails — is now under threat. A possible land transfer backed by the Trump administration would allow a joint mining venture to begin work on a proposed copper mine that would essentially collapse the site into a crater up to 1,100 feet deep and nearly 2 miles wide.

The looming date of that transfer, Aug. 19, is compelling Catholic sisters and other activists to support members of the Western Apache who are defending this sacred tribal site.

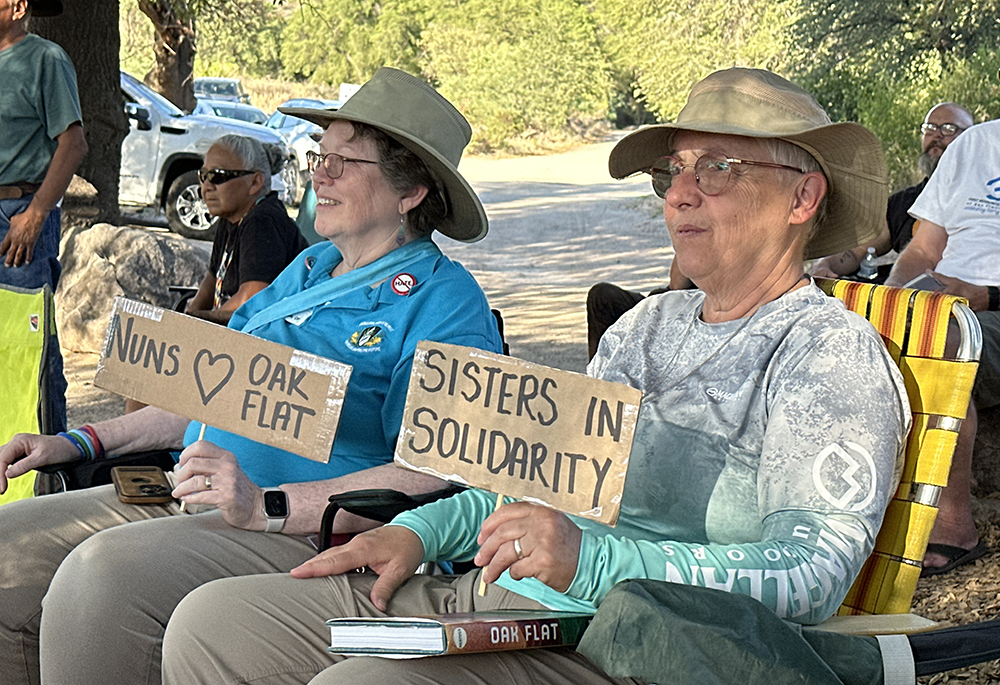

Under a tree canopy at Oak Flat, members of the Land Justice Futures delegation hold signs in support of Apache religious freedoms and rights. (Courtesy of Land Justice Futures)

Nine sisters representing seven congregations joined Apache elders and others during three days of peaceful demonstrations, July 18-20, in defense of Oak Flat, or Chi'chil Bildagoteel, as the Apache call it. The congregations included Sisters of Mercy, Dominicans of Peace, Sisters of St. Joseph, Sisters of Providence, Sisters of Loretto, Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and Sisters of Charity.

The delegation of 16 people, organized by Land Justice Futures, also included a religious lay associate and three Indigenous elders and partners. They were part of a larger group of demonstrators that totalled about 200 at its peak, joining in Apache prayer, song, dance and ceremony.

But that was not the only presence of sisters. Some 100 people, including representatives of religious communities who could not travel to Arizona in person, participated in a virtual online prayer service, on the second day of the delegation visit.

People gather in a circle for prayer after dance, song and teachings at Oak Flat. (Courtesy of Steve Pavey)

That prayer service was specifically written for Oak Flat by members of the Loretto Community in Kentucky, said Sarah Bradley, who headed the delegation, organized by Land Justice Futures.

Land Justice Futures, formerly known as the Nuns and Nones Land Justice Project, works with communities of women religious "to center racial and ecological justice in property planning decisions, forging relationships with Indigenous and Black movement partners and creating new futures on the lands and properties sisters have stewarded and owned," Bradley said.

The sisters who did attend in person — many of them older adults — sat in lawn chairs under the revered oak trees of the forested land, holding homemade signs that declared "Nuns support Apache religious freedoms," "Nuns [LOVE] Oak Flat" and "Complicit No More."

But when they could, and despite the challenges of high heat and dust, they stood and joined in dancing and acclamation.

Sisters sit under the oak trees at Oak Flat with signs in support of the community organization Apache Stronghold. In front, left to right: Sr. Kristin Peters of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and Sr. Joni Luna of the Sisters of Providence. In the back are Dominican Sr. Susan Leslie and Sr. Barbara Battista, Sisters of Providence. (Courtesy of Steve Pavey)

"I felt a call to be there — to be in solidarity with the Apache," said Dominican of Peace Sr. Susan Leslie. "I felt it was the right thing to do, and the right place to be."

"We need to stand up against the rape of the earth," she said.

Bradley said the physical solidarity between Catholic sisters and Indigenous elders "was a powerful witness and presence because the Catholic Church has done so much harm to Indigenous communities in the name of colonization and 'progress.' To stand together was deeply moving."

'For the Apache, it's not moveable — it's a place; it is this place. If this site is destroyed or desecrated, their religious practice will no longer have a home.'

—Dominican Sr. Susan Leslie

In interviews with Global Sisters Report, Bradley, Leslie, Sr. Barbara Battista of the Sisters of Providence and others spoke of the importance of championing Gospel values in the face of environmental threat.

Battista said that her public vows compel her to speak out when acts of power and injustice infringe on those values — in this case, on Oak Flat's historical, religious and cultural significance for Apache people, and the religious and cultural freedoms being threatened.

"This is all about standing up for life together," Battista said, "of honoring life, full stop."

The effects of the Doctrine of Discovery

Several themes within the cause are important here, sisters said. One is the recognition of the violence embedded in church and Western history, particularly through the Doctrine of Discovery.

That doctrine was based on papal decrees, known as bulls, that originated in the 15th century. The doctrine justified European-led colonization in the Americas and elsewhere leading to the violent seizure of indigenous lands.

Under the late Pope Francis, the Vatican repudiated the doctrine in 2023.

Leslie said she, along with other sisters and growing numbers of Catholics, are coming to recognize that the church "to which we belong has been part of the problem historically."

Dominican Sr. Susan Leslie, left, and Sr. Barbara Battista, of the Sisters of Providence, hold supportive handmade signs and listen to speakers at the Oak Flat event. (Courtesy of Land Justice Futures)

As such, it is important for her as a vowed member of the Catholic Church to say "no" to the continuing effects of the Doctrine of Discovery, "and to affirm values that promote healing and oneness."

"As a woman religious, it is something I can speak to," she said.

Another theme is the issue of religious freedom. Though the Catholic tradition affirms sacred sites — such as Lourdes, Assisi and Medjugorje — the tradition is not dependent on them, or even on church buildings themselves. The practice of Catholicism is embodied, and as such is "moveable," not dependent on a specific place.

That's not the case with the Apache, Leslie said.

"For the Apache, it's not moveable — it's a place; it is this place" she said. "If this site is destroyed or desecrated, their religious practice will no longer have a home."

Leslie said despite the differences between the Catholic and tribal faith traditions, she thinks there are essential commonalities: a reliance on God and a reverence for "listening to the spirit."

Jane German, a co-member of the Loretto Community, holds a sign at Oak Flat demanding the Supreme Court to do justice by the Apache. (Courtesy of Steve Pavey)

A critical mineral resource

To its proponents, the copper project is about concrete, not spiritual, matters.

In its approval of this and other land transfers, the White House said March 20 that "overbearing" federal regulations have "eroded" the "nation's mineral production."

In a statement provided to GSR, Resolution Copper, the mining project owned by two international companies, Rio Tinto and BHP, said that copper "is a crucial resource for America's energy future, modern infrastructure needs, and national defense."

"Ensuring a domestic supply of this critical mineral supports not only Arizona's economy but also the nation's broader economic and security goals."

Advertisement

Of the recent protests, Resolution Copper said: "We recognize there are different views regarding the Resolution Copper project, all of which we respect. We will continue our efforts to actively engage with groups to understand any concerns and how we can look to address them."

Leslie said she recognizes the current economic and technological pressures at play — noting that she and fellow sisters, like most Americans, use electronic devices whose manufacture are dependent on minerals like copper.

"But we've come to believe we need these things," she said. "We're confusing creature comforts with quality of life, and it's not the same thing."

A crowd, including sisters, listening to an Apache Stronghold ally and artist rap during recent Oak Flat demonstrations. Among those who spoke at the gathering was Wendsler Nosie, an Apache elder and leader of Apache Stronghold. Nosie told the visitors of the need "to stand together" and find common ground among different groups. (Courtesy of Land Justice Features)

Susan Classen, a lay co-member of the Loretto Community, acknowledges the complexity.

Though she was not at Oak Flat in July, she has visited the site twice this year and has closely studied the developments.

In June, she stayed at the Oak Flat camp as part of "prayerful accompaniment" offered to the grassroots community organization Apache Stronghold by the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery.

The Oak Flat case, Classen said, "is so much more than an environmental fight. … It touches on the historic treatment of Native Americans and how we define religious freedom."

"Religious freedom for Christians looks one way right now, and religious freedom for Native Americans another."

Solidarity among 'unlikely allies'

Like the sisters, Classen said the "solidarity" aspects are also important.

Those are also important to Pat McCabe, a Diné Navajo elder and teacher from New Mexico who was also a member of the Land Justice Futures delegation.

She said the time spent with the sisters "was reconciling in a way that is hard to describe."

"I am not a nun, but I was proud to be with the sisters," she said, adding she was "grateful for that level of embodied acknowledgment," noting the power of Apache people welcoming "unlikely allies."

The phrase "unlikely allies" is no accident. McCabe was the first generation of her family not to attend a Christian boarding school — in her family's case, Dutch Reformed Protestant. The experience of her parents and others from such schooling proved scarring and embittering, she said, and left bad impressions about Christianity.

McCabe sees Land Justice Futures-led work as a way for sisters to consider what the role of the institutional church has been in the lives of Indigenous peoples.

"To be in that conversation is becoming very powerful," McCabe said. But the issues surrounding that are not settled: Indigenous people want to see action, and not just vague promises, on such challenges as the eventual return of land to Indigenous groups by sister congregations.

'Religious freedom for Christians looks one way right now, and religious freedom for Native Americans another.'

—Susan Classen, a lay co-member of the Loretto Community

Considering the historical complicity of the church in genocide against Native peoples, McCabe credits the sisters who participated in the Oak Flat event who are willing to say, "We are complicit no more."

That evolution will take time, she believes, but what happened over three days at Oak Flat "is an interruption in the narrative, a narrative of church and empire" which inspired the Doctrine of Discovery.

Whatever the religious background, McCabe said, all present affirmed "a deeper authority being called forth from different spiritual paths. Oak Flat is calling that forth from us again."