Paramedic students Destiny Hatfield, left, and Lyn Garison, right, work through a simulated emergency medical scenario as teacher Sr. Kathy Limber looks on at Southwest Virginia Community College in Cedar Bluff. (Provided photo)

The mountains will let you know, he said.

In the back of an ambulance trust was born. While riding down a rough mountain trail on the way to a rescue, I had become their neighbor. I was one of them. The parish priest was right. The mountains had spoken. I was home.

In search of genuine spirituality, humility and compassion, I took a risk and changed my life. After two years of schooling and a year of field training, I arrived in Pocahontas, Virginia, to work as a paramedic in the "hollers" of Appalachia. After 26 years, I have come to love the mountains. Not just because of their physical beauty but because of the beauty in the life of the people. There is a peace that comes with the knowledge "I am where I should be."

Gifted moments in community, ministry and prayer have come with a shared life with the Appalachian community. Being a paramedic helped me to form a trusting relationship with the community. As trust developed, the community took me in not only as neighbor but eventually as family. As a family member, I was introduced to the way of life and culture that make the Appalachian people who they are.

Coal mining had been part of their culture for centuries. Father, son and grandson worked the mine. These mountain men spent years underground digging "black gold," the "black gold" that filled and scarred their lungs but fed their families.

Despite hardship, many of the women took pride in raising eight or nine children in two rooms — children who have now finished high school and have even gone on to college or to serve in the military.

Big George (Provided photo)

One of the emergency medical technicians I worked with, "Big George," stood 6-foot-3 and weighed 300 pounds. His hands were massive; once he had to do CPR on a 10-day-old infant. He told me later that he was so afraid that he would hurt the baby that he used just one finger to do chest compressions.

One of the miners told me that everyone working in the mines is "coal black," no matter what color they are at home. There is no difference down below, because everyone depends on the person next to them to get out safely at the end of the day. Relationships formed in the mines held strong even when the grime was washed away.

The vehicle crashed and the driver was thrown over the mountain side. One hundred yards down, his flight was broken by pine trees. He was alive. The volunteer firemen of the community got there quickly along with local men and women. How to get to him was quickly decided. The people formed a human chain. Hands grabbing hands, they stepped carefully down the side. They got to him. He was given initial emergency care and then with a simple rope and human strength he was brought to the top. In mountain country, it is what they do. Show up. Reach out. Hold hands. Save lives.

A man ran into the church yelling, "The flood water is coming." In a short time, a wall of water traveled down between the mountains into town. The creek grew to an uncontrollable raging river. Trailers disappeared as they broke apart from the force of hitting the bridge. Homes along the creek were gone. Those who lived on high ground opened their homes to those who lost everything. The strength of the people could be seen in the next days as the cleanup began. They would not be leaving; the spirit was there to rebuild. The mountains are their home.

J.D. had become frail for a 50-year-old man. He died, younger than normal. His family had no money to bury J.D., but in a very short time those at the Ambulance Authority who had little means themselves gathered enough money to bury their friend and co-worker.

Advertisement

This emergency medical system family then carried his casket up the steep mountainside to his family cemetery. All took turns digging his grave with one pick and one shovel, lowering him and then covering him with mountain dirt. They loved him. They gave him the noble and dignified burial that he deserved. They took care of one of their own. This is life in the hollers.

For me, life has taken many turns while traveling these winding mountain roads. Many lessons have been learned. During my 26 years of work here, as I stood side by side with the people in the hollers of Virginia and West Virginia, they shared their lives with me. They taught me. They embraced me. They called me to be my genuine self.

This has been a journey of joy, sadness, laughter and tears. I learned from them that in times of great difficulty, compassion helps the sun come over the mountain the next day. These people of the coal fields touched my heart with their care of each other.

They have showed me the face of God. They still do.

And I am grateful.

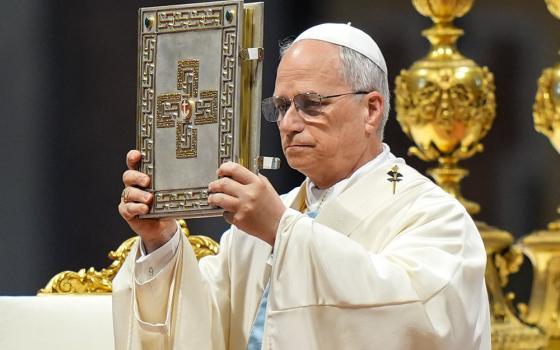

[Kathy Limber is a Sister of the Humility of Mary. Since 1993, she has served in emergency medical services as a paramedic and registered nurse in Southwest Virginia and Southern West Virginia. A co-founder of Catholic Community Service in McDowell County, West Virginia, she is currently the accreditation coordinator for the paramedic program at Southwest Virginia Community College.]