Migrants from Central America seeking asylum in the United States line up May 15 to be escorted to the main road by the Texas Army National Guard in Roma, Texas, after crossing the Rio Grande. (CNS/Reuters/Adrees Latif)

Global Sisters Report requested reports from sisters who have been volunteering at the U.S.-Mexico border in response to the humanitarian crisis there. This is the second and final group of those reports chosen for publication. Submissions are edited for length and clarity.

Sr. Darlene Pienschke of the Sisters of the Divine Savior in Milwaukee has spent two years ministering to migrants at Casa Alitas in Tucson, Arizona, where she is often inspired by the perseverance of those seeking a better life. But one of her most profound encounters came not at a center serving migrants, but at the apartment of an elderly American woman:

At Christmastime, I received a phone call from my beautician, Letty, a lovely woman who gathered and donated baby clothing after hearing of immigrant mothers giving birth at Casa Alitas. Letty told me she had shared about my ministry at Casa Alitas with another of her clients, Joan, and now Joan wanted me to contact her.

When I called the next morning, I could hear appreciation in her voice. Joan invited me to her home, saying she needed to talk to me in person. She explained she was elderly, unable to drive, and living with her daughter "way out in the desert." I arranged to visit the next day.

It was a joy for us to meet — and humbling. Joan is 100 years old, mentally sharp, and lives in a second-floor apartment. Her loving daughter lives downstairs. Joan crochets baby caps and blankets and has piles of each, which she generously gives away.

When Letty spoke with Joan about the immigrants' poverty, the dangers they were fleeing and Casa Alitas, the possibility to actually meet a nun who worked there stirred this woman, poor in spirit and heart. In meeting me, Joan would determine if I might be the path to realize her lifelong dream to help the poor in a tangible way.

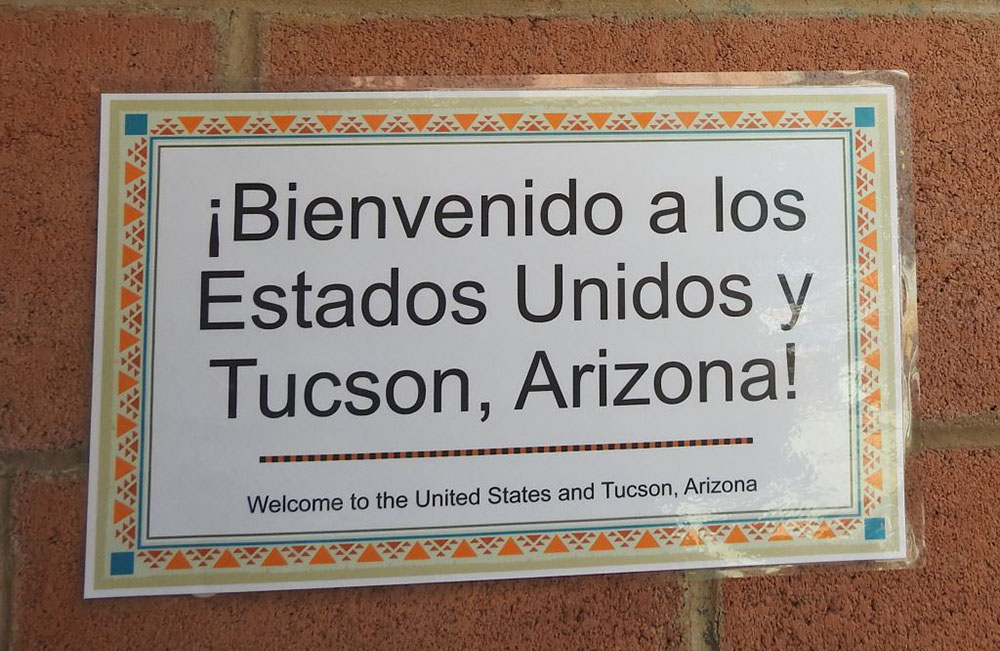

A welcome sign at Casa Alitas in Tucson, Arizona, where Sr. Darlene Pienschke has ministered to migrants for two years (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Divine Savior)

Spiritually, her heart and mind were one, set on a deeply personal and spiritual conviction that Jesus calls us to care for the poor. Her single-minded focus was to complete the important business to make her own mission come true.

Joan was at ease, with a gentleness in sharing her thoughts. She spoke about what Letty had shared and her lifelong interest and prayer for the poor. Then Joan surprised me, acknowledging that I was a Catholic sister and she wanted me to know she was Mormon. I told her I didn't think God cares if we are Mormon or Catholic. He made and loves us all and wants us to know him and the importance of how we live and care for one another.

Then Joan got up and retrieved an envelope. She told me she wanted to give to Casa Alitas for the care of the immigrant poor. Her check was for $2,100 — the sum of her retirement check. I was taken aback and voiced my concern that she would give away the entire amount. Her daughter gently interrupted to express support of her mother's decision. She explained her mother's reason for inviting me to her home was to meet me and learn about the ministry at Casa Alitas to help in making her decision.

Never had I experienced such complete self-emptying than in Joan's gift. It was as if the gift was a prayer. For Joan, I believe it was first a deeply spiritual offering to God, and then a gift for the poor. I was deeply moved by this holy expression of love for God and neighbor by a woman who personifies "poor of heart" and "solidarity with the poor." I will forever remember that holy moment.

I was deeply moved by this holy expression of love for God and neighbor by a woman who personifies 'poor of heart' and 'solidarity with the poor.'

We said our goodbyes, each of us deeply moved and grateful for our time together. As I drove away, I did not know if I would encounter this lovely 100-year-old saint again.

Several months later, Joan and her daughter phoned to ask if they could drop off crocheted baby caps and blankets. When they arrived, I invited them in, but they were on their way to another stop and only visited briefly through the car window.

Then, the week after Easter, Joan and her daughter stopped for a second visit — their purpose was to have me look over another check, to be sure Casa Alitas was spelled correctly. It was Joan's final stimulus check — $1,000. Again, I was beyond words to express their selflessness. I was sad to see them go so soon, but it gave my heart joy that, in spite of wearing masks for protection, we could meet again in a friendship we will forever cherish.

Normally, sisters responding to calls to help minister to migrants at the border work with adults and families. Unaccompanied minors, by law and court settlements, go through a separate system: They must be released from U.S. Customs and Border Protection to the custody of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Office of Refugee Resettlement within 72 hours. That agency must place the children into supervised care, such as family, foster care or licensed group homes. However, there has been such a flood of unaccompanied minors that the Office of Refugee Resettlement has set up facilities to temporarily house thousands of children.

Unaccompanied minors from Central America seeking asylum in the United States hold hands March 12 as they await transport in Penitas, Texas, after crossing the Rio Grande. (CNS/Reuters/Adrees Latif)

The Leadership Conference of Women Religious and Catholic Charities USA put out a call for help in those facilities. Adrian Dominican Sr. Mary Jane Lubinski responded and served through the archdiocesan Catholic Charities at the Freeman Coliseum in San Antonio, before HHS moved the boys out of the coliseum May 24:

Imagine looking out over a sea of cots in a vast convention center, coliseum or stadium. There are no dividers, simply cot after cot, side by side, row after row grouped into 36 pods with 30 cots in each pod — five rows of six. That comes to nearly 1,000 cots.

A second "dorm" of that size brings the number to 2,000 at Freeman Coliseum, where unaccompanied minors, all boys between the ages of 13 and 17, were sheltered safely and cared for on their long, arduous journey toward unification with family or sponsors in the United States.

They are brave, courageous, resilient boys from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador who have faced unimaginable trauma. Sent at the urging and sacrifice of family, they left everything they ever knew for a better future. One told of his mother's words echoing in his heart: "If you stay here, you will be dead." Hope outweighed the risk, and the journey began.

In spite of all that, the boys exude a sense of harnessed energy marked by playfulness, potential, promise and esperanza, hope.

Advertisement

I have learned that boys are a contact sport. They are playful with each other — the tweak of a toe as one passes the cot of another, a cap removed, a jab in the side, a fist bump or a leap on someone's back as they line up for meals or showers, and watch out for that soccer game! It is spontaneous, all in fun, done as soon as begun but joyful. It touches on the need for contact in a world that has grown foreign and cold.

Contact leads to relationships. Bonds of friendship develop between the boys at Freeman, which was obvious when one recently left the group to be unified with his family. The other boys lifted him high, and cheers arose with hugs all around as he bravely strapped on his duffle bag and headed off.

The 24-hour, seven-days-a-week compassionate care of sisters and volunteers from more than 20 religious congregations and numerous parishes restored hope that the promise of love is alive in America. It was particularly touching when a sister was asked to pray with a boy who just heard that his grandfather had died. Together, they moved to the altar to Our Lady of Guadalupe, decorated with countless origami flowers, trying to bring solace to the heartbroken child.

Promise and potential exude from the youth, and the sisters recognized it immediately as they taught English, presented American currency, reviewed mathematics, explained traffic signs and played card games with fierce competition and understanding.

These brave, courageous, resilient boys from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador exude a sense of harnessed energy marked by playfulness, potential, promise and esperanza, hope.

Two areas that were particularly notable were the arts. A local artist came day after day, volunteering his time and sharing his resources to work with the boys, encouraging them to give expression to their feelings. The outcome was breathtaking and displayed in the cafeteria for all to see. The quetzal, a beautiful national symbol of Guatemala, was often pictured along with the mountains and the setting sun.

Music, too, brought them to life. On Mother's Day, mariachis, a group of five women, raised the roof of the coliseum as the boys all converged near the stage, those in the back standing on chairs or cots to see. They reluctantly let the group leave after an encore because it was time for lunch — pizza and ice cream on a day that otherwise would be heavy with longing.

Esperanza and a future is what brought them here. These boys represent our hope, our future here in the United States, as well. For two months, the coliseum held our future artists, composers, doctors, craftsmen, architects, vineyard owners, truckers and so much more.

Sr. Sharon White of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Philadelphia served at the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, for 15 days:

Observing the dedication and leadership skills of the center's director, Missionaries of Jesus Sr. Norma Pimentel, inspired me with a deeper call to serve the immigrants who come to our country seeking asylum. These vulnerable people were our sole priority as we provided hospitality to everyone as far as we were able.

St. Joseph Sr. Sharon White shops for clothing and supplies for migrants staying at the Humanitarian Respite Center in McAllen, Texas. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

The center was a safety net for men, women and children who walked thousands of miles to cross the Rio Grande into Texas.

Their tired and worn faces, battered clothes and bare feet tore at my privileged heart. There were many moments when I experienced a burst of compassion. Once, a young dad with a family of four showed me that he was on his phone, and he and his family beckoned me to come closer with smiles and laughter. They were FaceTiming with their family in Honduras to show them that they made it to safety.

I celebrated, laughed and joined this family who welcomed me into their hearts. I assured the extended family on the phone that I was happy to be with their loved ones. We exchanged smiles and threw kisses. I said, "Tu familia es buena. Me encantan. Están a salvo. Dios está con ellos." ("Your family is good. I love them. They are safe. God is with them.")

But now, I must re-enter my world in Philadelphia. I feel a sense of guilt that I have too many clothes, plenty of food and a comfortable home. As I pray with a God who knows my heart, I ask: How am I now called to use the experience?

I do know that I have the responsibility to be an advocate, to change oppressive systems and to speak the truth. I can testify that people seeking legal asylum are not criminals coming to the United States to steal jobs or get a free ticket to housing, food or medical care.

Together, we need to find a solution so that people will not have to flee their homelands to seek a better life after they or their family have been threatened, tortured, raped, murdered, robbed and/or trafficked. In the meantime, I will do everything in my power to make room at the table for another hungry soul. It is an inalienable right.