Kamloops residents and First Nations people gather to listen to drummers and singers at a May 31 memorial in front of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia. (CNS/Reuters/Dennis Owen)

The Sisters of St. Ann, the religious congregation that taught at the Kamloops Indian Residential School where the remains of 215 children were discovered in an unmarked grave last month, has signed an agreement to share its archival records with the Royal British Columbia Museum and the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre at the University of British Columbia.

The memorandum of understanding was announced June 23 and was hailed by Daniel Muzyka, acting CEO of the Royal British Columbia Museum, as "a positive step" in the process of "truth-finding and reconciliation."

Sr. Marie Zarowny, president and board chair of the Sisters of St. Ann, said the congregation was committed to finding the truth and would assist the process in whatever way it could.

"From the time we first heard of abuse in the schools it was of utmost importance to us to learn the truth and to do whatever we could to contribute to making the truth known, to bring about a just resolution and to participate in activities that could lead to healing and reconciliation," Zarowny said in a statement to stakeholders. She also said there had been misinformation in recent weeks about her congregation's archives and its cooperation with government inquiries.

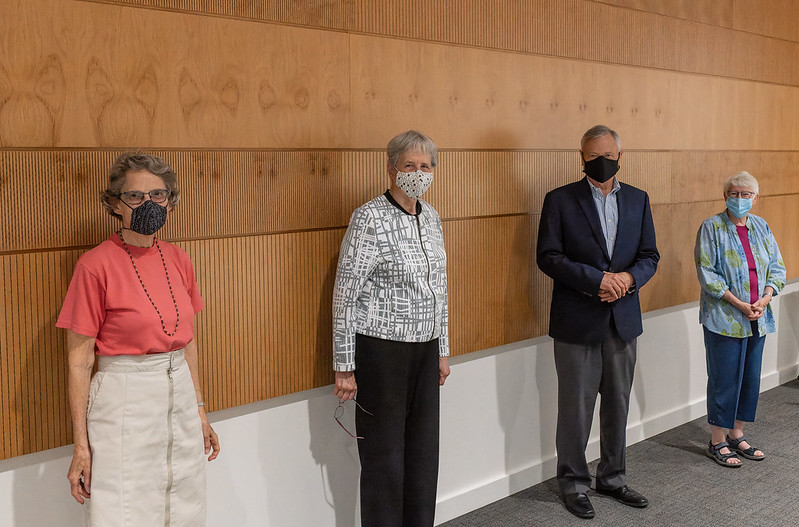

Sr. Marie Zarowny, left, president of the Sisters of St. Ann, signs a joint agreement to share archived materials from the First Nation residential school in Kamloop, British Columbia, with the Royal British Columbia Museum. Signing for the museum is Dan Muzyka, museum board chair and acting CEO. Canadian indigenous groups, investigators and the public have called for transparency since 215 remains of children were discovered in May in unmarked graves on the school site. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Ann)

The school at Kamloops was part of a network of more than 100 residential schools across Canada to which 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were sent between 1883 and 1996. Often, the children were removed from their homes against their families' wishes.

The Catholic Church ran about two-thirds of residential schools in Canada. The Kamloops Indian Residential School, which closed permanently in 1977, was mostly operated from 1890 to 1969 by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, who also ran a significant number of other residential schools across Canada. The Sisters of St. Ann taught at the school.

The children were not allowed to speak their own languages, and in testimonies to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, survivors recounted sexual, physical and psychological abuse. In 2015, the commission concluded that these schools were part of a program of "cultural genocide."

There have been calls for a national investigation into the deaths of the children buried at Kamloops and calls for it to be extended to other residential schools.

One of those who would like to see an independent examination of all burials at former residential schools is former Canadian senator and First Nations lawyer Murray Sinclair, who served as chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 2009 to 2015. He said June 4 there are too many unanswered questions, such as how many burial sites exist in Canada, where they are located and how many children are buried in them. Since the Kamloops discovery, he has warned Canadians that they should be prepared for the discovery of more children's remains at other residential school sites.

In the wake of the Kamloops announcement, Sinclair said hundreds of residential school survivors contacted him. He said the government denied a request from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to conduct a fuller inquiry to explore the stories survivors related about children who suddenly went missing and may have ended up in burial sites.

From left, Commissioner Chief Wilton Littlechild, Justice Murray Sinclair and Commissioner Marie Wilson unveil the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's final report Dec. 15, 2015, in Ottawa, Ontario. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pledged to work toward full reconciliation with Canadian aboriginals as he accepted a final report on the abuses of the government's now-defunct system of residential schools for indigenous children. (CNS/Reuters/Chris Wattie)

On June 24, the Cowessess First Nation discovered 751 unmarked graves of mostly children buried at the Catholic Church-run Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan, the New York Times reported. The school was operated first by four Sisters of Notre Dame des Missions de Lyon and from 1901 to 1979 by the Sisters of St. Joseph of St. Hyacinthe, according to the University of Regina in Saskatchewan.

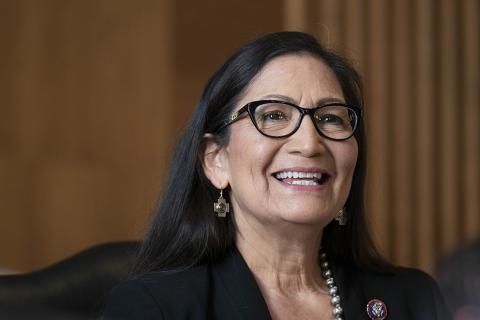

Rep. Debra Haaland (D-New Mexico) prepares to testify as secretary of the interior nominee during a Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee confirmation hearing in Washington Feb. 24. (Newscom/SplashNews/Pool via CNP/Sarah Silbiger)

Following the widespread shock over the Kamloops discovery, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Truth Initiative this week, which will investigate past boarding school facilities, possible burial sites near them, and the identities and tribal affiliations of children who were taken there.

In a June 22 memorandum, she said the Department of the Interior must address the intergenerational impact of Indian boarding schools in the United States to shed light on the traumas of the past.

Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, said thousands of Indigenous children were removed from their homes and placed in federal boarding schools across the country.

"Many who survived the ordeal returned home changed in unimaginable ways, and their experiences still resonate across the generations," she said.

Kamloops toll expected to rise

A report into the remains found at Kamloops is due to be published late this month, and Indigenous leaders have indicated that the figure of 215 may rise.

"Regrettably, we know that many more children are unaccounted for," Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc Chief Rosanne Casimir said in a May 31 statement.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimates that at least 4,100 students died or went missing from the residential schools, and it requested that the government account for those children by financing the search for burial sites at the schools. In 2009, the government denied the commission's request for $1.5 million to do this, as Sinclair said June 4.

The burial of the children in the unmarked grave at Kamloops was revealed by a geophysical survey method that uses ground-penetrating radar. High-frequency radio waves are sent into the ground and bounce back to the receiver if they hit anything different to soil, building an image of what may lie below. The method is used increasingly in forensic archaeology.

Writing for National Catholic Reporter this week, Kathleen Holscher, chair of Roman Catholic studies at the University of New Mexico, highlighted the discrepancy between the 215 children documented by the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc search team as buried in the unmarked Kamloops grave and the 51 student deaths at the school documented by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

"In other words, most children buried at Kamloops died deaths for which records — if they existed at all — have been destroyed or withheld from First Nations communities and the public," Holscher wrote. "The Tk'emlups te Secwepemc search was not solely to repatriate known dead (as important as those processes are), but also to learn fates of the disappeared, or children who went to school and vanished."

Scott Hamilton, chair of the Department of Anthropology at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, said that over about 140 years that Indian residential schools operated, the truth commission's research indicates that at least 3,213 children died.

Hamilton suggests in his paper "Where are the Children buried?" that this is a conservative estimate "in light of the sporadic record keeping and poor document survival, and the early state of research into a vast (and still growing) archive."

Lights illuminate shoes and stuffed toys outside of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School on June 6. The remains of 215 children, some as young as 3 years old, were found at the site in May in Kamloops, British Columbia. Pope Francis expressed his sorrow at the discovery of the remains at the school, which was run from 1890 to 1969 by the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. (CNS/Reuters/Jennifer Gauthier)

Papal apology awaited

The grave in Kamloops sparked outrage across Canada and prompted Pope Francis to express his pain and call for respect of the rights and cultures of native peoples. However, the pope did not give the direct apology for the harm and legacy of the schools demanded by former students and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Some Catholic religious orders and diocesan bishops have apologized in the past, as have leaders of the Anglican, United Church of Canada and Presbyterian churches, which also operated some of the residential schools. However, despite a personal appeal to the pope for an apology in 2017 by Trudeau and a vote in the House of Commons of Canada in 2018 asking the pope to formally apologize, that apology has yet to materialize.

The issue has created tension within the church in Canada, as is apparent from a June 18 letter to NCR from Paula Monahan in Etobicoke, Ontario.

A former major superior of the Discalced Carmelites — "the closest that a woman can get to being a bishop in today's Catholic Church" — she appealed publicly to Canadian Catholics to "demand that the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops fulfil its manifest ethical obligation: (1) to publish a formal apology; and (2) to pay its ethical share of compensation for the obscene treatment of Indigenous children in Roman Catholic residential schools across Canada."

Speaking to pilgrims in St. Peter's Square on June 6, Pope Francis urged Canadian political and Catholic religious leaders to "cooperate with determination" to shed light on the finding and to seek reconciliation and healing.

There have been many calls for the Catholic orders to share their records, particularly any that may provide a better understanding of how the children died in Kamloops and other residential schools.

"There is still work to be done," Jean-Michel Bigou, spokesman for the Canadian Religious Conference, told Global Sisters Report in regard to making all archival materials accessible.

"Both dioceses and religious congregations were involved in the residential school system. These entities are independent of each other," he said. "We can't say what is going on with the dioceses. However, in regard to the sharing of records by religious congregations, some have indeed shared and sent documents to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

"We understand, however, that there is still work to be done to digitize and make accessible all archival materials dealing with the administration of the residential schools in order to fully shed light on this management by the religious congregations involved," Bigou added.

Advertisement

Records still missing

The concerns around outstanding records were highlighted in a 2017 leaked memo from the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, which holds 7,000 survivor statements and other records related to residential schools.

The memo indicates that thousands of records and photos still have not been transferred to the center by some religious congregations involved in running the schools. The Sisters of St. Ann and the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, also known as the Grey Nuns, have been criticized for failing to sign waivers to allow for transfer of their files to the center, which is based at the University of Manitoba.

When GSR contacted the Sisters of Charity of Montreal and asked about claims that the community provided only 338 out of 3,493 photos considered relevant to the center's work, congregational leader Sr. Aurore Larkin declined to comment.

Ry Moran, director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, told CBC in June 2018 that "the onus is on the orders to supply the records."

However, in her letter to stakeholders regarding the agreement to share its archival records with the Royal British Columbia Museum, Zarowny of the Sisters of St. Ann said there had been "misinformation" in recent weeks regarding the archives, as well as "how we have provided records with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR)."

She said the congregation provided all its records related to Indian residential schools to the commission in November 2012 and that, prior to sending the records, commission staff visited the congregation's archives on several occasions and worked with them to determine the proper format for submission.

"We have numerous documents that show our continuing communication and collaboration with both the TRC and the NCTR," she said.

Zarowny also said that at the request of the commission, the congregation had done a thorough search of all its documents to identify the names of any children who became ill, died or were missing.

"We provided that list to the document gatherers of the TRC, as requested," she said.

The sisters were teachers in residential schools, so no official school records, including class registers, were the property of the Sisters of St. Ann and would not be in the congregation's archives, she said.

"These were all turned over to the administrators of the schools and are the property of the Department of Indian Affairs, the federal government department that ran Indian Residential schools," Zarowny said.

A June 23 statement from the congregation and the museum stresses that the Indigenous community's needs are at the center of the record review process.

"A priority is making Indian Residential School records and associated records that contain information about SSA involvement at residential schools accessible to Indigenous communities," it states. This will include sharing the records digitally.

From left: Sr. Judi Morin, canonical co-leader of the Sisters of St. Ann; Sr. Marie Zarowny, president of the Sisters of St. Ann; Dan Muzyka, board chair and acting CEO of the Royal British Columbia Museum; and Sr. Joyce Harris, canonical co-leader of the Sisters of St. Ann on the day the Sisters of St. Ann signed a joint agreement to share archived materials from the First Nation residential school in Kamloop, British Columbia, with the Royal British Columbia Museum. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Ann)

It said that staff at the British Columbia Archives will work with the Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre "as a neutral third party" to begin the process of auditing the sisters' holdings soon after July 1, when the agreement will take effect. It will remain in effect until all the work of reviewing and processing the records is complete and the sisters' archives are transferred to the British Columbia Archives at the Royal British Columbia Museum. The work will be finished by 2025, two years earlier than originally scheduled, the statement says.

The Sisters of St. Ann was founded in Quebec in 1850, and in 1890, nuns from the congregation began teaching at the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The congregation participated in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings on Indian residential schools.

Some apologies have been made

In the wake of the latest revelations concerning the Kamloops residential school, a number of religious congregations issued apologies.

Expressing their profound sorrow, shame and regret at the abuse perpetrated on the Indigenous people of Canada by both the Catholic Church and the federal and provincial governments of Canada, the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul on June 9 said: "We pray that the discovery at the Residential School in Kamloops will be a tipping point for all Canadians to implement the 94 Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission."

Constable Crystal Evelyn, a media relations officer with the Kamloops Royal Canadian Mounted Police, told GSR that on June 3, in response to questions about the residential school discovery, she spoke with Staff Sgt. Bill Wallace, the detachment commander with the Tk'emlúps Rural Royal Canadian Mounted Police. He said the Tk'emlúps Rural Royal Canadian Mounted Police is working closely with the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc community leaders in determining the next steps and the best way to be involved in any investigative avenues going forward.

"A file has been opened and any further actions will be taken in consultation with the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nations," Wallace told Evelyn.

But as Canada marked National Indigenous Peoples Day on June 21, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police confirmed they were investigating fires that day that destroyed two mostly wooden Catholic churches on Indigenous community land less than 100 kilometers from Kamloops. Sacred Heart Church on the Penticton Indian Band territory and St. Gregory's Church on the territory of the Osoyoos Indian Band, both more than 100 years old, burned hours apart.

Sgt. Jason Bayda of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police said in a statement that police were treating the fires as suspicious.

"Should our investigations deem these fires as arson, the RCMP will be looking at all possible motives and allow the facts and evidence to direct our investigative action," he said. "We are sensitive to the recent events, but won't speculate on a motive."

However, some believe the fires are linked to anger over the mass grave and the Catholic Church's treatment of the Indigenous people of Canada.

The unmarked burial in Kamloops has reopened the wounds of Canada's colonial history. A delegation including representatives of First Nations, Métis and Inuit national organizations will meet with Pope Francis at the Vatican before the end of the year, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops said in a June 10 statement.

Noting that some of the children found in the Kamloops grave were barely 3 years old, the Canadian Religious Conference said in a June 4 statement: "We make our own the words of Vancouver Archbishop J. Michael Miller, CSB, who declared, 'The Church was unquestionably wrong in implementing a government colonialist policy which resulted in devastation for children, families and communities.' "