Sr. Eva Fidela Maamo, a member of Sisters of St. Paul de Chartres, in the conference room at the Foundation of Our Lady of Peace Mission in Paranaque City, Philippines (Oliver Samson)

Days after the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in June 1991, St. Paul de Chartres Sr. Eva Fidela Maamo and the board of her Foundation of Our Lady of Peace Mission met with displaced Indigenous Aetas in Subic, a mountainous town about 80 kilometers (50 miles) northwest of Manila, the country's capital.

The eruption, which triggered massive lahar flows, claimed the lives of more than 1,000 people and displaced 1.5 million others, according to the government. Volcanologists considered it the second-largest volcanic eruption in the 20th century after Mount Novarupta in 1912.

The displaced Indigenous people were relocated in what is known today as Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center in Subic in the province of Zambales.

Maamo, a surgeon, observed that public health was one of the major concerns among the relocated Aetas. So she trained some tribe members to become "barefoot doctors" who could treat common diseases and raise health awareness in the community.

Advertisement

The nun, 82, trained her first batch of 17 barefoot doctors during her ministry in Lake Sebu, a mountainous town in southern Philippines, in the 1970s. At the time, the nearest hospital was in General Santos City, six hours away by foot. Getting a patient to that hospital would require crossing several rivers, as Lake Sebu, a 345-hectare lake with 11 islands and islets within its borders, is traversed by 40 major rivers.

In 1982, a few years after her superior recalled her to Manila, she established the Foundation of Our Lady of Peace Mission, which offers health services, livelihood training and assistance, educational aids, and formation. It also has feeding programs for children in economically poor communities in Manila.

In 2005, Maamo started training more barefoot doctors in Manila. She has now trained 274 barefoot doctors from the 110 Indigenous communities in the country.

St. Paul de Chartres Sr. Eva Fidela Maamo, right, poses with Madeline Garcia, Maamo's assistant secretary, at the Foundation of Our Lady of Peace Mission in Paranaque City, Philippines. (Oliver Samson)

"Barefoot doctors are not medical doctors," Maamo said. "But they have been trained to treat common diseases. We also encourage them to use proven medicinal plants in treating common ailments as part of preserving their cultural heritage."

Maamo founded Our Lady of Peace Hospital through local and foreign donations in 1992 and received the AY Foundation's Mother Teresa Award the next year. In 1997, she received the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award.

GSR: How did your ministry in the Aeta community come about?

Maamo: Our foundation received a request to relocate Aetas who lost their homes to the Mount Pinatubo eruption in 1991. During the eruption, they evacuated to an area near a river. They chose that particular area so that they could see the volcano every day. They worshipped the volcano. But the Aetas told us they might die if the volcano erupted again. They asked me to relocate them to a safer place.

After helping them rebuild their homes, what assistance did your foundation offer them?

We provided them with land so that they can grow crops and raise animals. We gave them pigs, chickens, and tilapia fingerlings. They grew the fingerlings in a fish pen. After they harvested the tilapia, they sold them at the market downtown. The local government of the Subic municipality offered the Aetas a space at the market for selling their produce.

Houses in Phase 4 at the Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center in Subic, Zambales. The village is subdivided into five phases. (Oliver Samson)

The foundation acquired 30 hectares of land for them. The government later gave them additional lands.

What do your Aeta barefoot doctors do to safeguard their community?

We trained eight barefoot doctors in the Aeta community. We built a clinic in 1993. It is supplied with medicine. The patients pay for the medicine.

The barefoot doctors take turns working in the clinic. We give stipends to those on duty.

A year after the barefoot doctors received the training, they were able to reduce the incidence of diseases in the community. Common health complaints were influenza, pneumonia and other respiratory ailments.

We initiated programs on health, education, livelihood, spiritual and values formation, and culture preservation.

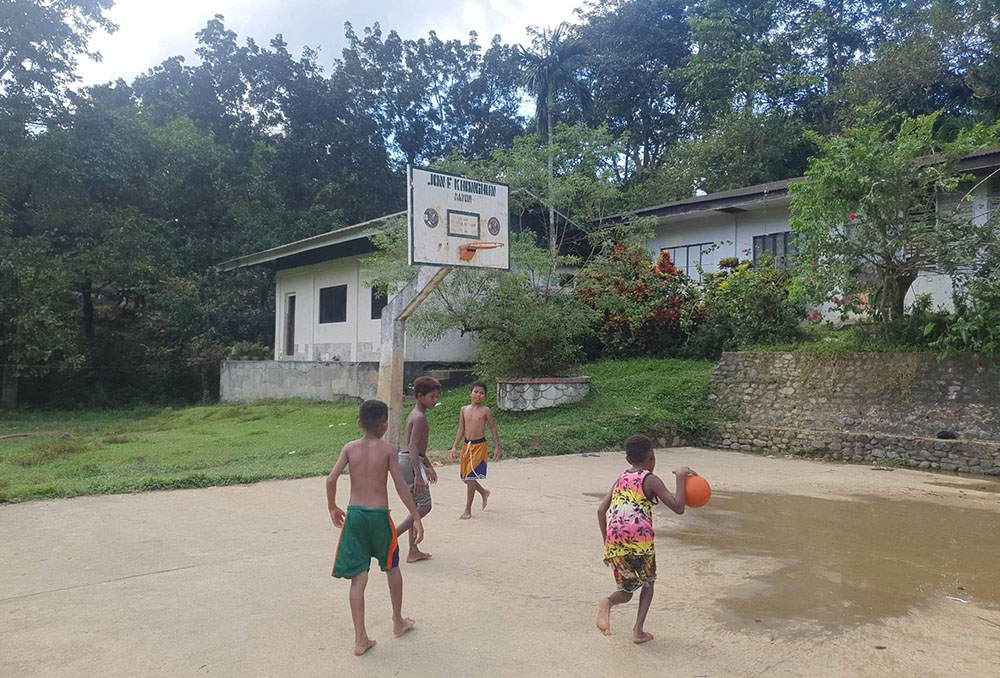

Children play basketball at the Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center in Subic, Zambales, Philippines. Most of the facilities are located in Phase 4 of the village. (Oliver Samson)

Your foundation also built schools in the community. How many Aetas have graduated?

The foundation set up a day care center right after the eruption. We built an elementary school and, later, a high school.

The Aningway-Sacatihan Elementary School Annex and the Aningway-Sacatihan High School are both located in the community and are now under the Department of Education. So far, a total of 84 students have graduated Grade 10.

For about three years, the foundation paid for the teachers' salaries. Today, it's the government that pays for their salary. After the government took over the schools, they started admitting non-Aeta students. But most of the students are still Aetas.

I'm grateful to the town mayor for being supportive to our programs.

Jolina Tablan (in pink), Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center coordinator, and students pose for a photo at Aningway-Sacatihan High School and Aningway-Sacatihan Elementary School Annex in Subic, Zambales, Philippines. (Oliver Samson)

Does the foundation offer guidance to your college scholars in choosing courses to take?

Yes. We schedule meetings with our scholars to guide them as to what course can greatly help in their development as individuals and in their development as a community. This year, we have three scholars who graduated in education, two in finance, and one in agriculture. We also have a scholar who is now a third-year nursing student.

How does the foundation help educate the Aetas on their rights as Indigenous people and on preservation of the environment?

We coordinate with the local government in organizing conferences and training on Indigenous people's rights and their right to ancestral lands. We also partner with various organizations who offer to raise their awareness.

Some Indigenous communities had been land-grabbed in the past. We have to educate and empower them.

How do you encourage them to address community concerns on their own?

We helped them form a tribal council that is independent from our foundation. Every two years, they hold an election for the council. The council is under the supervision of the National Commission on Indigenous People.

The Aeta Cultural Heritage Center at the Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center in Subic, Zambales, Philippines (Oliver Samson)

How do you encourage them to join religious formations?

I don't do any conversion work. But on one occasion, they told me about baptisms and weddings in low-lying and non-Aeta communities. They asked me if they could also get baptized and get married in the Catholic Church.

Some of the Aetas had more than one wife. So I told them to study the religion first. Then, I requested from the local parish priest to give us someone who could provide them with catechism. The Aetas studied the Catholic faith.

After about a year, they requested to be baptized. They were already practicing monogamy. Then we conducted a mass baptism and a mass wedding for them.

You built a chapel in their community.

We cannot accommodate all the Aetas in the chapel anymore. Almost everyone in the community hears Mass. They use the multipurpose building for the Mass since it can accommodate everyone in the community.

The old chapel at the Aeta Resettlement and Rehabilitation Center in Subic, Zambales, Philippines (Oliver Samson)

What other help do you see the Aetas need?

I think they need more sustainable livelihood and educational opportunities and programs for their development as individuals and as a community. Livelihood and educational opportunities can help them become more independent and empowered.

How many Aetas are involved in your ministry in Subic?

As of today, there are 146 families in the community, or 500 individuals.

What do you think encouraged them to convert to the Catholic faith?

They used to worship the volcano. But after experiencing the love and concern that we gave them, they became curious about the Catholic faith. They were actually the ones who requested for a mass baptism and a mass wedding.

The foundation was a bridge in their conversion to the Catholic faith and in their development as individuals and as a community.