Sr. Judy Dohner, pictured here in Cite Soleil, Haiti, worked as a nurse and hospital administrator in the Caribbean country from 2002 to 2018. She returned to the U.S. and now volunteers helping immigrants in Immokalee, and keeps tabs on the situation in Haiti, which she says is very bleak. (Courtesy of Judy Dohner)

Sr. Judy Dohner has a special vantage point about the chaos that is enveloping Haiti. She volunteers as a caseworker at Catholic Charities in Immokalee, Florida, where she helps migrants, many of them from Haiti, who need assistance after arriving in the small southwestern central Florida town, considered the center of much of the state's migrant workforce.

This is Dohner's second stint in Immokalee. A member of the Sisters of the Humility of Mary, a community of about 100 sisters in Pennsylvania, Dohner first began working in Immokalee in 1990 as director of Guadalupe Center, a nonprofit then affiliated with the Diocese of Venice, Florida, which provided a soup kitchen, and an after-school program for migrant farmworkers and their families. Many of those services are now offered through Guadalupe Social Services and Catholic Charities, where she now volunteers.

At that time, there were many abuses being suffered by the migrants, most of whom were Mexicans, although Haitians and Guatemalans were also among new arrivals. During her 11 years in Immokalee, she was an advocate for the farmworkers and rural poor. She helped negotiate getting a sports complex with a swimming pool to be built in the community. She also invited a federally funded rural transportation agency from Washington, D.C., to help establish a small bus system in the town.

In 2002, Dohner was invited to visit Haiti. A registered nurse, she knew her skills and experience would be helpful and said she felt God's call to minister in the country. Her congregation is not international, but it had a special connection with Haiti. In 1991, it had developed a "corporate witness" statement to "work in solidarity" with the Haitian people. Dohner's leadership helped two Indigenous religious congregations, the Sisters of St. Antoine and the Little Sisters of St. Therese, with formation and construction projects in Haiti.

"When I saw Haiti, I knew this was my next step after Immokalee. I told my community that my ministry is a 'mission within a mission, a call within a call,' to live and work among people who are most poor and vulnerable without the benefit of safety nets," she said. In 2002, she moved to Port au Prince, Haiti, and began working with Fr. Rick Frechette, an American Passionist priest and a physician. Together with his team of young Haitian men and women, they worked daily in street clinics throughout the poorest slums in the city.

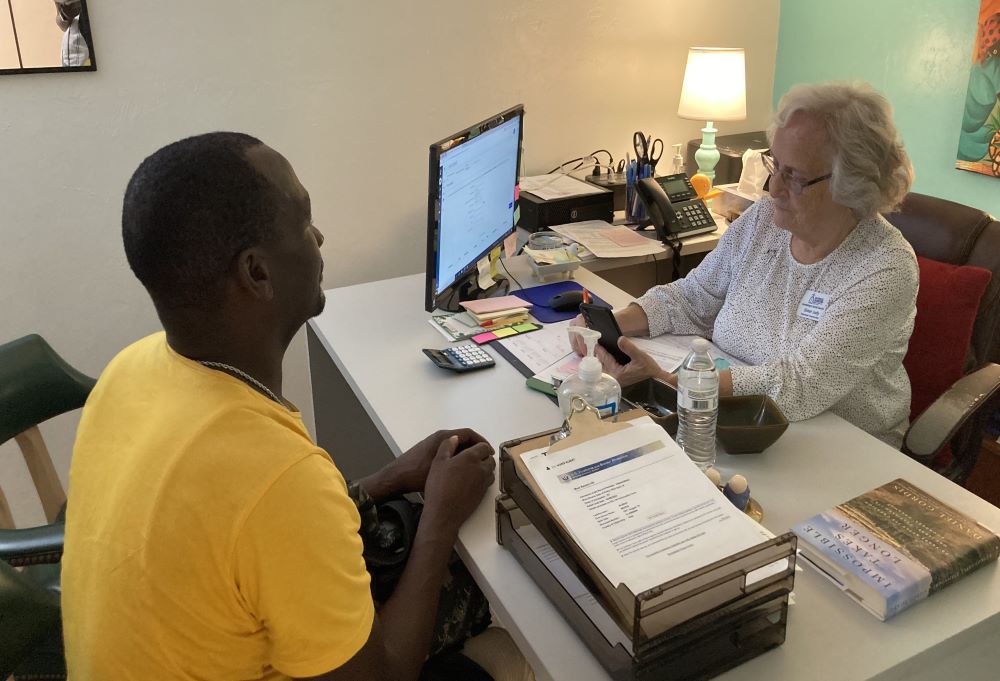

Sr. Judy Dohner helps migrant workers and immigrants through the Guadalupe Social Services center and Catholic Charities. Many face difficult hurdles with Floridat's strict immigration laws, which prevent them from working. (Courtesy of Judy Dohner)

Going to and from the clinics, they often had to dodge demonstrations or were stopped by bandits. In 2004, Dohner became the administrator of a children's hospital in Pétion-Ville and helped coordinate the construction of a new children's hospital in Tabarre. In 2008, she went to live and work in the mountains in southern Haiti with the Sisters of St. Antoine. She ran a rural clinic there and worked with the formation of the young sisters. In Fondwa, about 50 miles from the capital of Port-au-Prince, she learned fluent Creole since she was the only non-Haitian in the village.

She was injured while living in Fondwa during the devastating earthquake of 2010. The village was destroyed and, in spite of her injuries, she returned to Port-au-Prince and became the director of the emergency room at the children's hospital in Tabarre that had become a trauma center for those injured in the earthquake.

"It was really, really hard and I was really, really traumatized, as were all the people," Dohner said. "There would be violent aftershocks that would have everyone running out of the hospital for fear it would fall. I would have to go out and find the staff and convince them that God was protecting us."

After ministering in Haiti 2002-2018, Sr. Judy Dohner, a nurse, continues to work in Immokalee, Florida, with immigrants from the Caribbean Country. (Courtesy of Judy Dohner)

She was asked to take over as hospital director on an interim basis until a Haitian could be found. The country experienced a severe cholera epidemic, so a cholera center was also developed. She then became director of a small hospital and clinic in Cité Soleil, the biggest and poorest slum in Haiti, also a project of Frechette's. "I just learned to live with chaos and drama all the time," she said.

In 2018, at age 73, she decided her work in Haiti was done. She returned to Immokalee, where she continues to keep tabs on what is happening in Haiti as well as working with Haitians in the local community.

GSR: How would you gauge the situation in Haiti now?

Dohner: I would say there is no end in sight to the chaos all over the country. There is no functional government; kidnapping has become a business, the people live in fear every day. There are now over 300 armed gangs all over the country. In 2004, there were less than 40.

What do you see as a solution?

Democracy is not working. A country needs a strong middle class and stable finances for democracy to work and Haiti has neither. Perhaps a benevolent dictator is the answer. Only the Haitians can really answer this question. They want a good life and one that is safe. They do not want to leave their island, but they want pi bon viv (a better life) and they do see any hope for it in Haiti at this time.

Advertisement

What other issues does Haiti face in addition to the gang violence and political instability?

There seems to be no one to help the Haitians out of their morass. In July, the U.N. Security Council approved a yearlong multinational security force to be led by Kenya. (In August, Kenya's Supreme Court placed a temporary order lasting until Nov. 9 barring the Kenyan troops from proceeding with this intervention. The Kenyan government said Nov. 9 that its troops would not be deployed until conditions for training and funding are met. It's not clear when that will happen.)

There has been a "brain drain" out of Haiti since the assassination of their president several years ago. Haitians who are educated and have businesses or professions have left Haiti by the thousands.

Being a nurse and having worked in health care in Haiti, I have a theory that infant and childhood malnutrition have had a deleterious effect on much of the population's ability to have the necessary thinking skills to have a stable country. Because of this, the school system is broken, and the financial system doesn't function well. If physicians and nurses leave Haiti, their credentials are not accepted in other countries. Most of the judges have moved out of Haiti and the prison system has become life-threatening to the prisoners.

Sr. Judy Dohner, a Sister of the Humility of Mary, served as a nurse and hospital administrator in Haiti for 16 years. In 2018, she returned to the U.S. and volunteers at Guadalupe Social Services and Catholic Charities in Immokalee, Florida, considered the center of Florida’s migrant workers. (Gail DeGeorge)

What about the Haitians who are arriving in Florida, in Immokalee — what are their greatest needs? How have Florida's new strict immigration rules affected them?

There are no easy answers to the complex immigration issues facing the United States. I am seeing young Haitians and their families arriving after years in Chile and Brazil. They went there seeking a better life and did not find it. They could not get permanent residency or citizenship; often they could not get work. So, they traveled mostly on foot over 7,000 miles, then waited at the Mexico border to be allowed to seek asylum in America.

Having entered the U.S. via Florida, they now have new and difficult hurdles to face. They are not allowed to work and are limited in any government assistance they might receive. They are taken advantage of in housing. For example, they are asked to pay $600 a month for one room in a house where the whole family stays. Other rooms contain other families, so there may be 18-plus people in a house with one bathroom and one kitchen. The landlord is making $2,400 or more a month.

With Florida's new rules, there are many migrant farmworkers, who have lived and worked in Immokalee for years, who were afraid to go north this past spring. Those who went north are afraid to return to Florida because they are undocumented. Many of them can no longer work because of the new rules.

One solution to the immigration problem, while bigger solutions are decided, is to permit people coming in through the border to work. Who will pick the crops? Who will work in the packing houses? Or in landscaping, or in the chicken and pig farms in the north? These people want to work, they want a better life. They need to send money back to their families who are suffering. If they could work, they would not need government benefits and could better take care of themselves. I see that finding work and having decent housing are the greatest needs for the newly arrived Haitians seeking a better life and for all the immigrants trying to come to America at our southern borders.