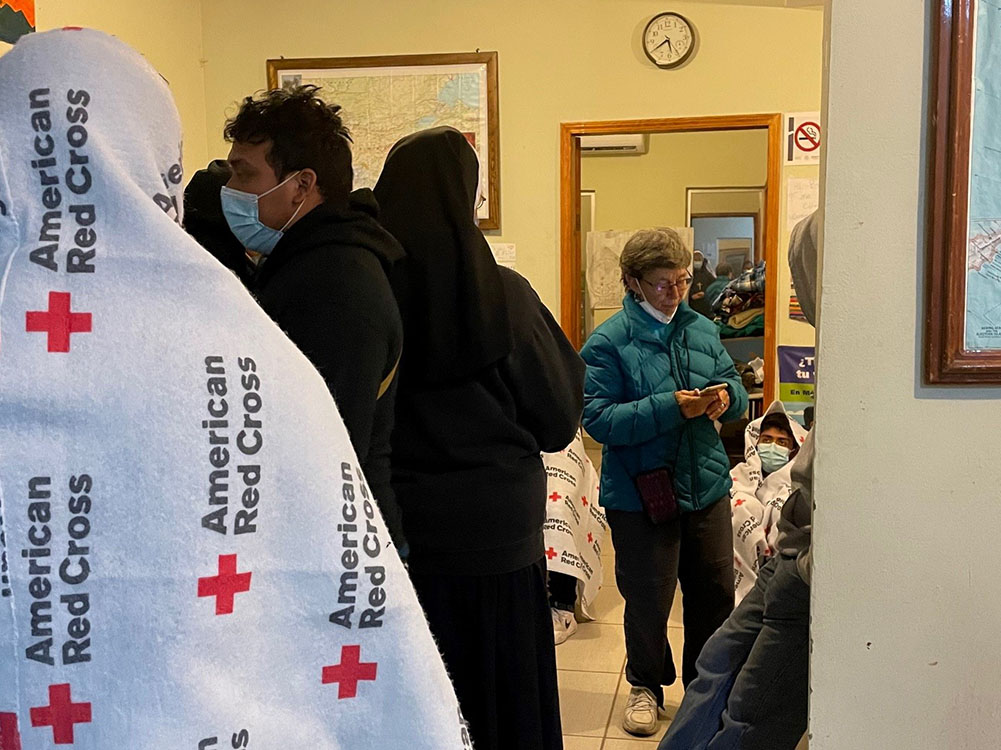

Sr. Judy Bourg (in green coat), a School Sister of Notre Dame, speaks with volunteers and returned migrants on an early morning in October 2021 at the migrant resource center in Agua Prieta, Mexico. (Peter Tran)

In 2010, Sr. Judy Bourg with other School Sisters of Notre Dame began a border ministry in Douglas, a southern Arizona town adjacent to Agua Prieta, a town in the northeastern corner of the Mexican state of Sonora. Today, the sisters' ministries include a migrant carpentry school, women's sewing and garden cooperative, planting crosses to remember those who lost their lives in the desert, a life experience border exposure program called Mission Awareness Process, and a humanitarian water drop-off to prevent migrants from dying on the desert trails.

Bourg also serves daily at Centro de Recursos Para Migrantes, the migrant resource center in Agua Prieta.

Born in New Orleans, Bourg celebrated her 50th anniversary as a School Sister of Notre Dame in August 2021. She has served in educational and pastoral ministries in Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi and in Guatemala before opening a School Sisters home in Douglas, Arizona.

The migrant center is run by Frontera de Cristo, a Presbyterian-based organization that provides border ministry on both sides of the line. Frontera also works in partnership with religious orders and church and secular organizations to address immediate needs and root causes of mass migration and create safe opportunities that help migrants. Members of the School Sisters of Notre Dame and the Missionary Sisters of the Eucharist are working as volunteers at the center.

The Centro de Recursos para Migrantes, or Migrant Resource Center, in Agua Prieta, Mexico, stands ready to welcome deported migrants at 2 a.m. one morning in October 2021. (Peter Tran)

Bourg talked to Global Sisters Report in late 2021 about her daily work at the center as well as recalled some stories of the migrants that motivated her to be a "link of hope."

GSR: Tell us about the daily life at the Migrant Resource Center and your early shift.

Bourg: Centro de Recursos para Migrantes has served deported and repatriated men and women migrants for 15 years. The School Sisters of Notre Dame have been volunteering there for 11 years. The volume of returned migrants, who were picked up in the desert by the U.S. Border Patrol, has fluctuated from year to year. In the past year, we have received an average of about 125 "returned" migrants a day. [The U.S. Customs and Border Protection would call them "expelled."]

We, first of all, offer a warm welcome to these returned men and women who have risked their lives in the desert of Arizona. We offer a safe place where they can rest and have a moment of quiet to decide what their next steps will be. On the second floor of the migrant center, we have cots and foam mattresses, where migrants can rest for a few hours before they rejoin their guide who will take them to the border to try to cross again.

At the moment, we offer a sandwich of ham and cheese, Café Justo, a definite favorite on the very cold mornings, a protein bar or other snacks, clothing in the winter, hoodies, sweatshirts, knitted hats, gloves, socks, underwear and pants. In the summer, we offer T-shirts. We also offer simple medical care for blisters, cuts from barbed wire, twisted ankles and knees and muscle pain, and medicines for cough and diarrhea.

For volunteers, our schedule starts at 2 a.m. and lasts until midnight some days. Border Patrol has been asked to return migrants to Agua Prieta only during daylight, but they have refused, citing the COVID virus as the excuse.

Advertisement

I cover the 2-5:30 a.m. time slot. I get up each morning at 1 a.m. [in Douglas] to go to our center [in Agua Pietra] near the border gate. For me, it is very moving to greet the migrants at the gate, welcome them and invite them into our aid center for food and a hot cup of coffee, along with warm clothing and a safe place to rest. It is dark and cold and they have no idea where they are. To be able to look them in the eyes and tell them that they are welcome into a safe place where they can rest fills my heart. Their gratitude is palpable, and men have cried.

Could you explain who these people are? Why were they deported?

These men and women are not seeking asylum. They are looking for a job in the U.S., where they can earn a just salary so that they can offer their family a better life, as all parents desire.

Because of Title 42 [which allows custom officers and border patrol agents to turn back migrants and asylum-seekers to Mexico or their home countries if there is a serious danger of introducing a communicable disease into the U.S.], they are not sent to detention, nor do they see a judge, but are summarily returned to Mexico, and many times not near the port of entry that they crossed.

All they want is work. As they have no "legal" way to secure a work permit into the U.S. and out of desperation, they feel forced to enter into the desert and risk their lives. The jobs in Mexico and in Central America do not pay sufficient money for them to provide food, education and health care to their children. These are "salt of the Earth" men and women who are hard workers. I would want these people as my neighbors.

Migrants help out at the resource center's garden in October 2021. Normally, their stays at the center in Agua Prieta, Mexico, are brief, long enough to rest, eat and decide on their next steps after being returned to Mexico. (Peter Tran)

You see them, face to face. Tell us some of their stories that inspire you.

There are many.

Alejandro from Chiapas arrived at our migrant center very weak and dehydrated. His main complaint was that his arm was really hurting. We realized that a catheter was left in his arm, where a Border Patrol agent had administered four units of electrolytes to him.

Alejandro explained that he had walked through the Baboquivari Mountains [in the Tohono O'odham Nation] with his traveling partner, a woman from Oaxaca. [Many times, cartels divide migrants in twos.] They walked in these treacherous and high mountains for six days, and for two days, they walked without water.

Rosa, his walking partner, could not walk anymore and was dying. There was no one around to help them. Alejandro stayed with Rosa until she died. He covered her up as best he could and continued to walk and crawl through the mountain passes. Finally, he arrived at a Border Patrol road, where he collapsed and the agent put the four units of fluid into his arm and saved his life.

Instead of being taken to the hospital, he was "deported" to Agua Prieta and ended up in the center. He was upset that he had to leave his new friend, Rosa, alone in the desert, and the BP agent was not interested in hearing where he had left her.

He cried while telling us about this. At the center, Alejandro was very weak, and at one point, we thought we would lose him. We called the Red Cross. They took him to the hospital, where he survived. We helped Alejandro return to his wife and twin girls.

In this past year, many migrants spoke about human remains that they have seen in the desert and the mountains. They all express regret and shame that they cannot stop and bury the person, but they know if they stop, they too will die. This trauma and guilt will haunt them for a lifetime.

This view of the Sonoran Desert looks south toward Mexico from about 50 miles north of the border. (Peter Tran)

One migrant told me that he was walking along and he saw a man and a woman sitting together with their arms around each other. As he walked closer to them, he realized that they had died recently. I could see in his face and through his tears that this was the memory he would not be able to erase.

In my volunteer work with the Samaritans, I place water for migrants in areas where migrants walk. At the migrant center we usually announce that if someone has seen human remains of a person in the desert or mountains, they are invited to share that information with me. If they can give me definite signposts that can be easily identified, I would call No More Deaths search and rescue group. They will go to recover the remains.

A few days ago, an older man named Samuel arrived at the center. He arrived with a group of 11 young men. It was around 3 a.m. I invited the group in. They immediately told me that they had with them an injured person. I thanked them and continued to serve them.

At one point, I looked up and saw two young, small Indigenous men from southern Mexico helping Samuel, who was injured, into the center gate. I was impressed to see how all the young men were so concerned about this older guy.

School Sister of Notre Dame Judy Bourg (seated at right) and other volunteers write upbeat messages to migrants on water jugs at a drop-off site in the Sonora Desert in October 2021. (Peter Tran)

We bought him in and sat him down. He was in a lot of pain. As I was alone and continued to welcome and give food to those who were arriving, these young men became my helpers. They helped me take off Samuel's boot, wash his foot, apply ice and salve, etc. They gave him water, electrolytes and pain medicine. They helped him with coffee and a sandwich. I would check in on them when I could.

At first, I thought that they were relatives or friends, but they were not. They were from Puebla, and Samuel was from Guerrero. After Samuel shattered his ankle in the desert, a diagnosis from the hospital where he went when we called the Red Cross, these young men stayed with him and helped him walk until they were all picked up by Border Patrol.

I knew these young men had given up their dream to reach their family in the U.S. in order to help Samuel, whom they did not know. He surely would have died. This type of generosity and concern occurs more often than we know. I was truly moved to see the care these young men had for a stranger.

One day, two migrant friends came into the center, each limping from terrible blisters. They ate their sandwich and drank their coffee and were waiting to have their blisters treated. They came into the building and they sat down side by side in front of Sister Maribel [Lara Hernandez] while I was looking on. She was deftly working on one of their feet when I overheard their conversation with each other.

During an October 2021 water drop, Ajo Samaritans and volunteers encounter migrants in the Sonoran Desert outside Ajo, Arizona. Sr. Judy Bourg, who has been participating in water drop-offs along the migrant trails for years, says this is the first time she saw migrants in the desert. (Peter Tran)

One of them was reprimanding the other about why he did not just "leave him" in the mountains. He was saying that all he wanted to do was die, as he was so tired. "Why didn't you just leave me there to die?"

His friend replied, "How could I leave you there? You are my best friend."

Maribel and I were trying to ignore the private conversation, but it was so emotional. They were talking to each other, not even noticing us.

The exhausted friend turned to his friend, saying, "You stopped and forced me to get up three times, yelling and screaming at me to get up. Why did you do that?"

The other responded, and by this time, both were crying: "I could not just let you die. You are my best friend."

By this time, Maribel and I also had tears in our eyes. A gift given.

How do you see the relevance of the School Sisters of Notre Dame ministry in southern Arizona?

When we first moved to Douglas in August 2010, we took time to reflect on what name we wanted to give our community. We settled on "Enlaces de Esperanza," or Links of Hope. We saw ourselves as SSNDs as bridge-builders and connectors for people and groups. We wanted to pull people together to share their gifts and desires, not tear people apart through focusing on differences and divisiveness.

We have become part of the lives of so many people during our 10 years of ministry on the border, and we are grateful to have tread this holy ground.