My work to advance the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth's mission to care for the Earth often leads me to reflect on the ideal relationship between people and the land. (Julia Gerwe)

Editor's note: Notes from the Field includes reports from young people volunteering in ministries of Catholic sisters. A partnership with Catholic Volunteer Network, the project began in the summer of 2015. This latest round of the series features volunteers in Orange, California; Nazareth, Kentucky; and New York City. Read more about Julia here.

A few weeks ago, I tested positive for COVID-19. I must say, I was surprised. I had been having some mild to moderate cold symptoms and wanted to test to rule out COVID infection ahead of some meetings and weekend plans. I figured I had a seasonal cold. When the test came back positive, it instead ushered in a period of isolation, rest and unexpected reflection.

When I started to feel sick, I heard my body's internal alarm system notifying me that something wasn't right, so I tried to sleep a full eight hours at night and drink more water. I limited further schedule engagements and in-person contact, but kept up with my work and duties at my normal pace. Testing positive for COVID-19, however, elevated the small alarm bell inside of me to a blistering screech — and ow! Screeching can hurt your head after a while. I had to step back, listen to my body, and rest. I didn't really have a choice to leave my apartment, and I didn't really have a choice to rest, either.

I've certainly been fortunate: My symptoms were mild, and I live alone and don't have others relying on me to provide food, care or supplemental income while I've been sick. To even work flexible, paid hours from home is a privilege I know many don't have. As I slept (a lot), filled up on soup and tea with honey, and rejoiced in my community of care that brought me meals, juice and love, I realized that this coronavirus cold was calling me to rest. My body had been telling me for some time that I needed to move slower and prioritize care; I just hadn't been a very good listener.

This not-so-gentle reminder for me to actively listen to my body forced me to confront a larger question: How am I currently listening and taking care? What isn't working?

These questions led me down a rabbit hole of sorts, calling me to consider how my understanding of "caring for self" is informed by my worldview, my assumptions, and my own role of privilege in an increasingly unequal world.

I realized shortly after opening Pandora's box of reflections in solitude that my first mistake was buying into a deeply entrenched doctrine of how I viewed my body and the world around me: as something to look after and as something far removed from Divinity.

Advertisement

Taking notes from cultural cues and church teachings in this arena hasn't served me well. Culturally, many of us could not go a day without talking or hearing about diets or workout plans to change the way we look, or surgeries or accessories to modify our bodies.

From the church, I knew that my body would never be perfect because the sacred doesn't reside in the flesh. Years of classroom religious education about the separation between spirit and body, the flesh being weak, etc., left me confused about how everything God created was so perfect and lovely except my own body.

Today, I recognize that the subliminal cultural messaging and this confused theology serve their own purposes to reinforce social paradigms and hierarchies rooted in power and privilege. I take supplemental notes from Barbara Brown Taylor, who writes in An Altar in the World: A Geography of Faith:

"The daily practice of incarnation — of being in the body with full confidence that God speaks the language of flesh — is to discover a pedagogy that is as old as the gospels."

I agree with her assertation that "I find myself rebelling against any religious definition of goodness that leaves the body behind."

When I became sick, I realized that viewing my body as separate from my being and outside of the Divine was actually making me sicker. From the outside, I saw my body as something to control, to remedy, to fix. When my body is as much a part of me as my personality, my quirks, and my soul, however, I desire to learn from her and work with her to live the highest quality life possible.

This realization lends itself to a deeper reimagining of how I view and connect with other "homes," communities and systems I find in this world.

This healthy pond ecosystem near Nazareth, Kentucky, where I live and serve, illustrates well the interconnectedness of all species and how this mutual interconnectedness supports sustainable living. (Julia Gerwe)

Take, for example, our collective relationship to the land. I've touched on this theme before, but my quarantined questionings dug deeper: How do I interact with the world around me, and how does this inform my understanding of self?

In my work and life, I often reference the idea of stewardship to illustrate a better relationship with creation. Biblical stewardship is a nice, digestible idea: Let's work together to responsibly manage the land that God entrusted to our care. The role of a steward seems better than the role of a master in dominion over creation, so it must be good.

However, the evolution of perspectives from being masters over nature to stewards of God's creation are rooted in the same truths: Humans are outside of and above this creation, which is to be managed or stewarded. Eco-feminist thinkers elaborate on this perspective best, including Lynn White Jr., who drew connections between the ecologic crisis and a perspective of human domination over nature as early as 1967 in "The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis."

When we envision ourselves at the top of the pyramid, existing independently from the systems that sustain us, we are not practicing incarnation as Barbara Brown Taylor or I would define it. Embodying ourselves in this world of carnal flesh can and should be a primary spiritual practice of a life rooted in justice and peace.

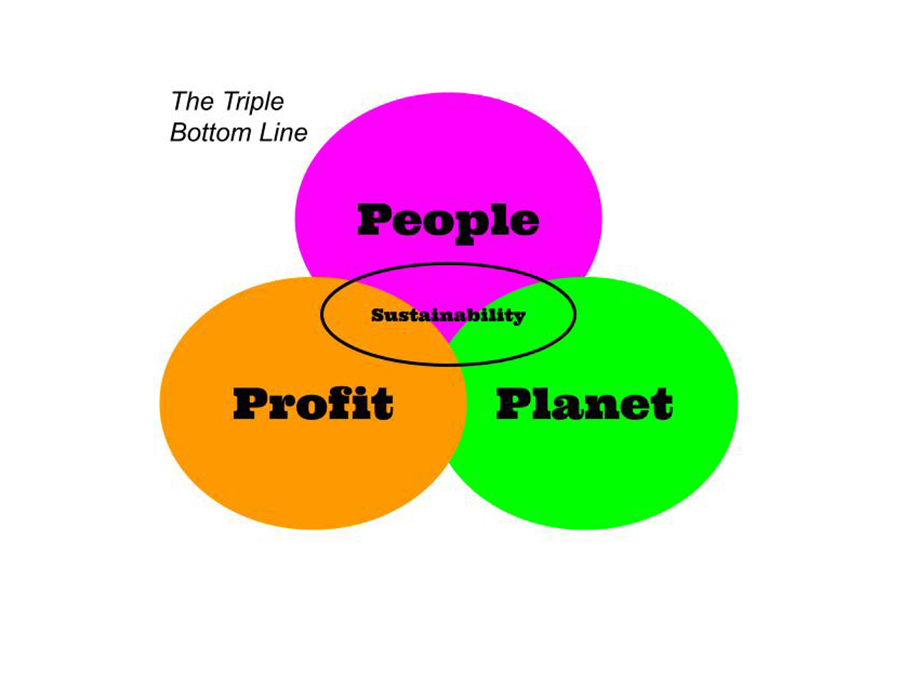

The triple bottom line business approach uses intersecting circles to represent the connections between people, planet, and profit, ultimately holding that sustainability exists at the intersection of all three. (Illustration by Julia Gerwe)

This lesson carries further implications about how we can live into our role in wider (eco)systems to promote justice and equity. The systems that sustain us are powerfully intertwined, but we so often live as if nothing is connected.

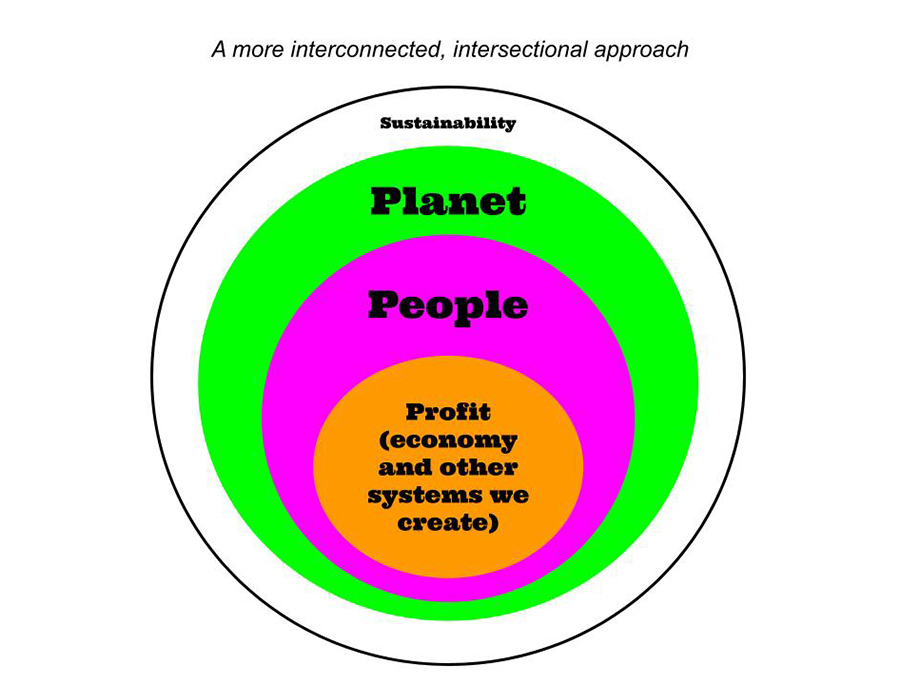

Instead of looking toward the "triple bottom line" — a business approach asserting that sustainability lies at the intersection of people, planet and profit — we should see ourselves (people) as concentric circles, a body embedded in the larger systems that sustain us (planet), using systems that we create (profit) to live sustainable lives.

When we reorganize these connections in our brains and our vernacular, it gives us power to reimagine unjust systems that we've created and to live sustainably within the physical limits of our Earth.

A more intersectional and interconnected approach between ourselves and systems around us uses concentric circles embedded in one another to illustrate that sustainability lies within recognizing our role as a part of and within creation. (Illustration by Julia Gerwe)

The truth is that for many issues surrounding social and environmental justice, we don't have time to argue semantics. People are dying, the poor are getting poorer, and the Earth is suffering dramatic atmospheric changes because of human-caused planetary warming. I believe, however, that these semantics will determine how we heal our relationship to each other and to our Earth.

When we start seeing ourselves are part of larger systems of creation, we are empowered to act within our means to effect change in ourselves, our businesses, our communities and our world.

For example, because we recognize that we cannot live sustainably within our planet's finite resources the way we have been living in many developed countries, we can encourage our communities to take dramatic action to invest in renewable energy and divest from fossil fuels instead of supporting carbon-offset projects that sequester carbon but maintain current levels of greenhouse gas emissions. (This is particularly appropriate timing to consider this question: The theme of Earth Day 2022 is "Invest in our Planet.")

Further, because we recognize that more equitable futures for all begin with us, we can examine our business practices to ensure that we pay living wages and offer benefits that reflect a more just world in which all have access to live well.

This shift in perspective inspires us to take action where we are. We just have to have the courage to reimagine, question and act.