Zofia Luszczkiewicz, left, and Anna Abrikosova (Courtesy of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Krakow*/Catholic Newmartyrs of Russia)

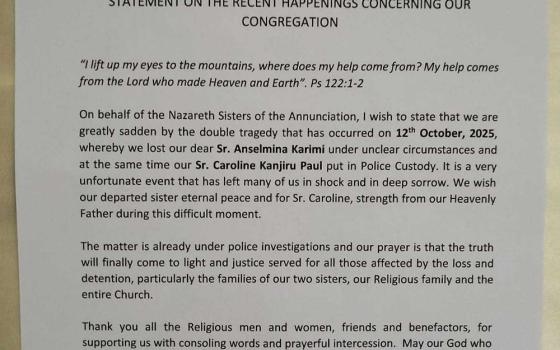

When the Polish church filed a document with the Vatican this August, proposing the beatification of 16 members of the Sisters of the Congregation of St. Catherine the Virgin and Martyr, it was a vivid reminder of the hardships inflicted on religious sisters under communist rule in Eastern Europe.

The nuns, aged 27 to 65, all died martyrs' deaths at the hands of Soviet soldiers in the northeastern Warmia region during the 1945 reinvasion of Poland, and were among over 100 killed from the St. Catherine order alone.

It was just one of numerous brutal episodes involving Catholic nuns that, three decades after communism's collapse and the Nov. 9 felling of the Berlin Wall, many now hope will become better known. A full account is needed, some Catholics say, in the interests of historical accuracy, as well as to illustrate the virtues involved in acts of testimony and martyrdom, and to ensure that the courage and endurance of religious sisters are accorded proper recognition.

Even today, however, the tight control exercised over media appearances means few religious order leaders are prepared to talk to journalists. Requests by GSR for comments on communist-era suffering from Poland's Conference of Higher Superiors of Female Religious Orders received no reply.

"Certainly, the situation of nuns was different here than in neighboring countries — the worst sufferings were confined to the 1940s and 1950s, after which planned repressions were abandoned in the face of resistance," Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, a Catholic presenter and expert with Polish Radio, said in a late October interview with GSR.

"But the whole story has hardly been told, even now, and the sisters involved have remained in the shadows while attention focused on the persecution of priests. It should be an inspiration for younger members of religious orders, as well as for the church and wider society," she said.

People stand atop the Berlin Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate in this Nov. 10, 1989, file photo. Catholic bishops from the European Union marked 30 years since the breaching of the Berlin Wall with tributes to those who worked for peaceful change, as well as warnings against resurgent "ideologies behind the building of walls." (CNS/David Brauchli, Reuters)

The assault on sisters

When Eastern Europe was overrun by Stalin's Red Army at the end of World War II, the newly installed communist regimes moved quickly to neutralize the Catholic Church.

Historians concur that religious orders were seen as secretive organizations threatening the officially atheist Communist Party's absolute power, so they became key targets for repression.

Hundreds of books have been published about the communist-era persecutions. A few used as sources for this story include a new Polish-language book by Agata Puścikowska, War Sisters; a two-volume book in Slovak, co-edited by František Mikloško, Gabriela Smolíková and Peter Smolík, Crimes of Communism in Slovakia 1948-1989; and a Romanian book by C. Vasile, Between the Vatican and the Kremlin.

In Romania, Catholic orders were banned outright in 1949, their houses closed and ransacked; and while most nuns were sent to labor camps, a smaller number, mostly elderly and infirm, were moved to "concentration cloisters."

In Bulgaria, where orders with foreign headquarters had already been outlawed, the Eucharistic sisters saw their Sofia chapel turned into a sports hall, while over a dozen surviving Carmelite nuns were given heavy prison terms.

Up to 700 Catholic convents in what was then Czechoslovakia were seized in a coordinated action in 1950, leaving an estimated 10,000 nuns incarcerated in prison and detention centers.

Many had qualified as teachers, doctors and translators but were set to work as farm laborers, weavers and fruit pickers when they refused to renounce their vows. Others were sent to "centralized convents" such as Bilá Voda in Moravia, which became home to about 450 incarcerated sisters from 13 orders.

In places like this, the orders continued recruiting and training members in secret, putting them through novitiates under cover of regular jobs.

In other countries, habited orders were later grudgingly permitted, but only after their schools, clinics and care homes had been seized and many nuns killed or imprisoned.

In Hungary, the regime opted for quick overnight swoops like Czechoslovakia's, trucking nuns to internment centers and withdrawing legal status from at least 60 orders.

A petition to the government deplored how nursing sisters had been peremptorily sacked and others offered bribes to abandon their communities. But Hungary's Culture Ministry was adamant: The orders were "nests of anti-state agitation."

Zofia Luszczkiewicz, a musician and nurse from the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, pictured (center) with two fellow sisters in an undated photo (Courtesy of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Krakow)

In Yugoslavia, where female orders had run over 300 kindergartens and schools, Catholic nuns were pilloried in the communist press and accused of mistreating children.

The Zagreb-based Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul* order, accounting for a third of Croatia's 397 convents, saw its hospitals and orphanages seized as organized religious life became impossible. By the early 1950s, two dozen sisters had been killed and some 40 were languishing in prison.

In western Poland alone, 323 convents and religious houses were closed in August 1954 in a special operation, "X-2." Over 1,300 nuns from 10 orders were rounded up by armed militia and bused to labor camps, where tuberculosis was rife and there was often no electricity or sanitation.

Eyewitnesses testified that Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary had been beaten, kicked and threatened with guns when the Urząd Bezpieczeństwa security police broke into their convent in the early hours at Bochnia, allegedly seeking dangerous Nazi collaborators.

"Our sisters were employed in service of the Church and worked among the sick — how could they have threatened public security," the superior general, Demetria Cebula, later demanded in a letter to Poland's communist boss, Wladyslaw Gomulka. "The only crime they committed in the eyes of the authorities was wearing the monastic habit."

German troops march through Warsaw, Poland, in September 1939. The invasion marked the start of World War II. (CNS/National Archives)

Retracing the story

Orders that remained legal in Poland later braved dangers trying to help underground sisters in other countries, despite the closing of borders and intense secret police surveillance.

Buoyed by the Polish pope, St. John Paul II, female orders quickly revived across Eastern Europe after 1989. Though vocations have since dropped sharply, Poland itself is now home, according to a January 2019 report by the Polish church's Catholic Information Agency, to around 18,000 nuns from 105 orders and congregations.

Beside the male clergy who dominate the headlines, however, nuns keep a low profile, leading some Catholics to fear their heroic communist-era role could be forgotten.

Although hundreds of books have detailed the testimony of priests such as the martyred Blessed Jerzy Popieluszko (1947-1984), it took until 2009 for the first full-length study of operation "X-2" to be published by Sr. Agata Mirek, a history professor at the Catholic University of Lublin.

"The attack was carefully prepared over a long period — the communist rulers knew the sisters had great authority and were afraid people might come to their defense," Mirek told Poland's Catholic Information Agency. "They hoped to persuade as many as possible to give up their religious orders, while also inducing some to collaborate as informers in a surveillance of monastic circles."

Attempts to make nuns collaborate achieved little success.

Zofia Luszczkiewicz, second from the left, pictured in a hospital room in an undated photo (Courtesy of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, Krakow)

Although one in 10 male clergy are estimated by Poland's National Remembrance Institute to have acted as secret police informers, with highest recruitment rates during the 1980s struggle with the Solidarity movement, no more than 30 of Poland's 27,000 religious sisters succumbed to police pressure during the decade.

Attempts to force them to place bugs in presbyteries or bring complaints of sexual harassment against male clergy almost always failed, researchers point out, while few ever left themselves vulnerable to blackmail and intimidation.

Glabisz-Pniewska, the radio presenter, is among those believing this impressive record should be better known and acknowledged.

"Most people associate nuns with work laypeople wouldn't do in care homes, hospitals and orphanages, or helping in parishes — they're hidden away and say very little about themselves," she told GSR.

"Given their relative physical weakness in the face of violent persecution, they had to be even tougher than male clergy. But little of this is being acknowledged," she said.

Witness and martyrdom

Stories of heroic witness have come to light elsewhere too.

In Slovakia, where dozens of nuns were jailed on anti-state charges under communist rule, a member of the Daughters of Christian Love, Florina Boenighová, was arrested by StB secret police agents in 1951 at the hospital where she worked in Nitra, and accused of running a secret novitiate and seminary.

On trial, the nun insisted she had merely honored her vocation to help the needy. But she was handed a 15-year sentence, despite suffering diabetes and pleurisy, and buried in an unmarked grave when she died five years later, aged 61, in Prague's Pankrac prison.

Conditions were even harsher in the Soviet Union.

In Russia, most Catholic priests and nuns had been shot or imprisoned within two decades of the 1917 revolution. Yet religious life limped on.

The Eucharistic sisters ran secret houses in Georgia and Kazakhstan, while nuns from Latvia and Ukraine held makeshift services for Catholics in Siberian camps and factories.

Anna Abrikosova (Courtesy of Catholic Newmartyrs of Russia)

A community of Dominican tertiaries, led by Anna Abrikosova in Moscow, had been broken up in 1922, and by a new wave of arrests and forced labor sentences in 1931.

Abrikosova's nuns showed great courage, refusing to testify against her and insisting the Soviet police had no right to scrutinize their spiritual life.

"They were heroines deserving our admiration," Russia's last Catholic bishop until 2002, Pius Neveu, told the Vatican in a dispatch; and they had "added a glorious page to the history of our Holy Mother Church."

Jailed in 1934, Abrikosova died in Moscow's Butyrka prison, aged 54, two years later. Her ashes were buried in a mass grave at the nearby Donskoi Monastery.

But at least two of her Dominican community, Nora Rubashova and Vera Gorodets, were still at large, teaching and doing charity work, in the 1970s.

In Soviet-occupied Lithuania, where religious orders were liquidated by 1948, Catholic resistance drew heavily on the work of secret nuns, with many doing daytime jobs while discreetly melting into the background.

Jolita Sarkaite, who joined the Sister Servants of Mary Immaculate after studying physics and astronomy, is gratified that Soviet-era veterans still outnumber younger order members, offering an example of courage and endurance to Christians still facing persecution across the world.

"Lithuania itself is free now, and we can organize our communities in relative peace," Sarkaite told GSR.

"But we all know this is very largely thanks to the struggle waged by that older generation, who are still a great source of richness for the Church and contemporary society."

Sarkaite's order, founded for non-habited nuns in 1878, claimed several famous names during the Soviet period.

One, Sr. Nijole Sadunaite, was declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International after being sent to Siberia in 1975 for helping circulate the Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania.

After her release, Sadunaite resumed her activities undaunted, using wigs and disguises to shake off KGB trails, and helping make the Catholic chronicle the Soviet Union's most comprehensive samizdat, or underground journal.

In 2018, the nun became the first woman to receive Lithuania's Freedom Medal. Now 81, she remains modest about her achievements.

"Each age brings its particular problems," Sadunaite told GSR.

"At that time, we were defending our rights and standing up for the persecuted, whereas now we face other challenges. But my own aim is still what it's always been — to help the poor and downtrodden."

Camilla Kruszelnicka (Courtesy of Catholic Newmartyrs of Russia)

The search for recognition

While stories like Sadunaite's are well known, in part thanks to her 1988 book, A Radiance in the Gulag, those of thousands of other former underground nuns who took their vows secretly at great risk are still being pieced together, while the church is also beginning to recognize their witness.

In 2001, when St. John Paul II beatified 27 Ukrainian Catholics, the list included Tarsykia Matskiv, a Sister Servant of the Congregation of the Handmaids of Mary Immaculate, shot by a marauding Russian soldier at her convent door in 1944, and Laurentia Herasymiv and Olympia Bida, both of the Congregation of Sisters of St. Joseph, who died at Tomsk in Siberia.

In 2003, Sr. Zdenka Schelingová, a Holy Cross nun from Slovakia, was similarly beatified, 48 years on her death following a 12-year sentence for helping detained priests, during which she was denied sacraments and mutilated by torture.

A martyrology commission, launched by the bishops' conference of Russia, is gathering material for the beatification of at least 13 martyrs, including Anna Abrikosova and a follower, Camilla Kruszelnicka, who was executed near Sandormoch.

Meanwhile, the research continues.

Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, a Catholic presenter and expert with Polish Radio (Provided photo)

In Poland, the 16 St. Catherine sisters from Warmia whose beatification is being sought, include Maria Abraham, an orthopedic nurse from Tolkmicek, who died from a beating shortly after recovering from TB, and Rozalia Angrick, who was shot in the neck while resisting soldiers who entered her convent at Lidzbark.

Srs. Agata Bonigk and Barbara Rautenberg both died being dragged behind a speeding truck, while others perished after being deported to Soviet labor camps.

Sr. Lucja Jaworska, the process postulator, regrets sufficient documentation has been collected only for the present 16, who chose to stay in their posts as nurses, teachers and catechists despite knowing the dangers facing them.

"Treated with callousness and cruelty by Soviet soldiers, they died because they were nuns – for the faith, in defense of honor and out of love of neighbor," Jaworska told Poland's Catholic Information Agency. "Everyone who knew them has testified to receiving grace from them."

Such stories may not be for the faint-hearted, and are only illustrative of the many Catholic nuns who died as martyrs in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

Advertisement

Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska thinks they firmly contradict, on the 30th anniversary of the 1989 revolutions, any lingering stereotypes of religious sisters as submissive and pliant servants of the church.

"Despite this heroic record, nuns still remain confined to the margins here," the Catholic radio presenter told GSR.

"Despite all the changes worldwide, we're only beginning to hear about their communist-era struggles. We must hope they gain more of a public voice — at least so this epic story can at last be properly known."

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]

*This story has been updated to correctly identify Luszczkiewicz's order as the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, and to correctly cite the order throughout the story.