Chicago Benedictine Sr. Karen Bland with a client of Grand Valley Catholic Outreach in Grand Junction, Colorado, where Bland is executive director (Courtesy of the Benedictine Sisters of Chicago)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

Editor's note: More than 1.6 billion people worldwide live in substandard housing. Of those, at least 150 million have no home at all. In this special series, A Place to Call Home, Global Sisters Report is focusing on women religious helping people who are homeless or lack adequate shelter. Over the next few months, we will examine how homelessness and a lack of affordable housing affect teens and young adults, families, migrants, the elderly and those displaced by natural disasters and climate change in stories from Kenya, India, Vietnam, Ireland, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, the United States and elsewhere.

Roan Head is bent over the table, carefully making ladder stitches in tiny fabric pillows about the size of a pack of cigarettes and talking about his history of mental health issues.

When the pillow is nearly done, he fills it with rice, then stitches it closed: It's a hand warmer that with 30 seconds in the microwave will give 30 minutes of heat — a small comfort to someone on the street with nowhere to go.

Head, 22, is on staff at the YMCA Safe Place Services day shelter for 18- to 24-year-olds in central Louisville, not far from where millionaires gamble on the "sport of kings" at Churchill Downs. But he started as a client.

When he was released from a mental hospital in the fall of 2017, Head knew he couldn't go back to where he had been living, which was with an uncle who was only making things worse.

"He would say, 'If you want to kill yourself, go ahead, and I'll help you,' " Head says. "Eventually, I tried."

So when he was released, he had nowhere to go.

"Living on the streets was easier than where I was coming from," he says.

YMCA Safe Place Services staff member Roan Head sews hand warmers for the day shelter's clients in Louisville, Kentucky. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

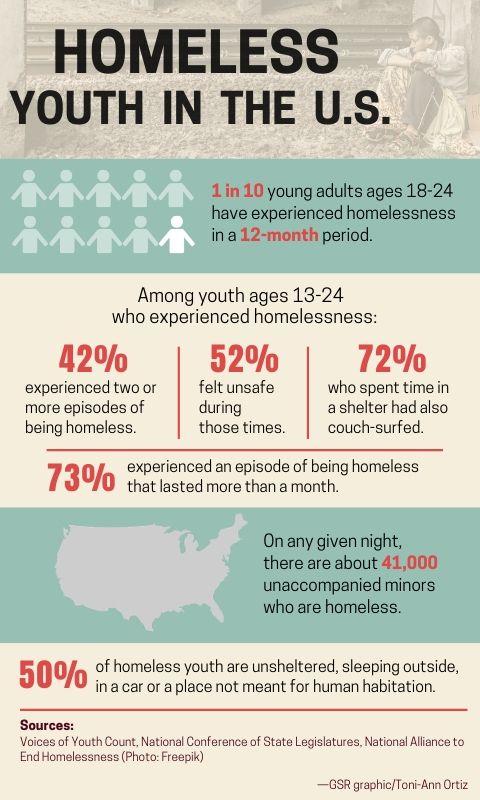

On any given night in the United States, 41,000 unaccompanied youth ages 13-25 are without a home. And on all of those nights, Catholic women religious are working to shelter them, feed them, and protect them.

Within days of his release from the hospital, Head found Safe Place Services and its youth development coordinator, Sr. Corbin Hannah, a Sister of Providence of St. Mary-of-the-Woods.

He began working at a grocery store and was able to afford housing. A case manager at Safe Place helped him get certified as a peer supporter, which gave him the opportunity to share the things he had learned with other clients. This led to an internship at the shelter and, eventually, a permanent position.

"My ability to cope on a day-to-day basis is much better," Head says. "Overall, my outlook is positive. I believe there can be and will be a good future."

Most of the clients at Safe Place work, Hannah says, yet they're homeless.

And now, with the COVID-19 pandemic closing businesses, jobs have disappeared. The temporary jobs many depend on — working at events, stadiums or catering — are nonexistent. But the day shelter is considered an essential service and continues to operate, Hannah says.

The shelter is big enough to maintain social distancing unless there are more than 10 clients at a time.

"The homeless don't have the luxury of staying home or having social isolation," she says. "They're much more vulnerable."

Not only do Safe Place's clients struggle to find jobs that pay a living wage, but there is an acute shortage of affordable housing.

According to a 2019 study by the Louisville Affordable Housing Trust Fund, the city has only enough affordable housing units for 54% of the city's families that live below the federal poverty line, currently about $26,000 a year for a family of four. To provide affordable housing for all families below the poverty line, the city would need an additional 31,000 affordable homes.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition says that to afford a one-bedroom apartment in Louisville, a worker must make at least $13.23 an hour. The minimum wage in Kentucky is $7.25.

The problem is not only in Louisville.

Sr. LaVern Olberding, a Sister of St. Francis of Clinton, Iowa, ministers in La Mesa, California, where she volunteers at an interfaith homeless shelter. One of the families she sees often is a father and two sons who live in their car.

"He keeps them in soccer, keeps them in school, he has a job," Olberding says. "The sacrifices these parents go through to give their kids as normal a life as possible is amazing."

They might appear to blend in seamlessly with those around them, she says, but they cannot find housing they can afford.

"I don't think there's a single child that's been in one of these situations that I would have picked out as homeless or as living outdoors or as disadvantaged," Olberding says. "It tears me apart."

And it is not only large, urban areas. Voices of Youth Count, an initiative of Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, found homelessness rates of both youth and young adults nearly identical in rural and urban counties: 4% for youth ages 13-17 and 9% for young adults ages 18-25.

Sr. Barb Freemyer, a Sister of Mercy, works at Stephen Center in Omaha, Nebraska, which offers emergency shelter, permanent supportive housing and transitional living to those with nowhere to go. Nebraska public schools reported more than 3,400 students — about 1% of the state's 319,000 students — experienced homelessness over the course of the 2016-17 school year.

"It's everywhere," Freemyer says. "It's all over."

'You are totally broken'

Benedictine Sr. Karen Bland is executive director of Grand Valley Catholic Outreach in Grand Junction, Colorado, where the National Low Income Housing Coalition reports a worker making the state minimum wage of $12 per hour would have to work 73 hours a week to afford a one-bedroom apartment.

Each child that comes to Grand Valley Catholic Outreach gets a new book while their parents seek services. Bland says they give out about 1,500 books a year, not only for the child's growth and development, but to help calm a child traumatized by what their family is experiencing.

And when it comes to homelessness among young people, trauma is a constant.

Bland says mental illness can often lead to homelessness, which leads to the trauma of living on the streets. But the trauma of living on the streets can also lead to mental illness, even among those who did not have those issues when they lost their home.

"What we've noticed over the years is that people who find themselves on the streets and it seems a dead end to them, that's when mental illness really escalates," Bland says. "So yes, there may be some people on the streets because of mental illness, but there are others who become mentally ill because of the trauma they experience just living on the streets — especially women."

Freemyer says children and young adults are resilient, but sustained trauma can have profound effects on development.

"I think it doesn't matter your age. What matters is that you are totally broken," Freemyer says. "There's also probably addiction and alcohol issues, and if you stay on the street too long, all of that is heightened. ... Either one precipitates homelessness, or they grow as they stay out on the street."

Every situation is complex

In Louisville, Troy (who asked to use a pseudonym because of the stigma attached to homelessness) has stopped into Safe Place to shower and do some laundry. He's been working as a dishwasher at a chain restaurant and has finally secured an apartment. But he can't move in.

"They told me there's a cockroach problem, so I have to wait," Troy says.

Rent is only the first step: He has no furniture, no dishes, no can opener. So while he waits to move in, he's trying to save money for the things he'll need to make it happen.

Even youth who were part of a state safety net are at risk of living on the streets.

"We see a variety of situations," Hannah says. "Some have aged out of foster care. Others had family conflicts over either sexual orientation or gender identity. Others have addictions, or their parents do, and they left as soon as they turned 18."

Troy (not his real name), left, is a client at YMCA Safe Place Services in Louisville, Kentucky, where Providence Sr. Corbin Hannah, right, is youth development coordinator. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

According to Covenant House, which serves homeless youth in New York City, more than 50% of those aging out of foster care or juvenile justice systems when they turn 18 will be homeless within six months.

Voices of Youth Count found that LGBT youth are 120% more likely to become homeless than their peers. Those from households with an annual income of less than $24,000 are 162% more likely to face homelessness. Youth who are single parents are three times more likely to be homeless, and youth without a high school diploma or GED are 346% more likely to be on the streets.

Every situation is unique, but more importantly, every situation is complex. And the complexity grows when young people are on the street.

"They don't trust people. They get kicked out of places because of their behavior," Hannah says. They don't have their birth certificates or Social Security numbers or identification, all of which they need to get a job. They don't have transportation or a place to shower or wash their clothes. If they have any valuables at all, they have nowhere to keep them."

In 2015, Sr. Pat Bombard, a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, helped coordinate a group of faculty and staff at DePaul University in Chicago to address the issue of homeless students. Bombard is the director of Vincent on Leadership: The Hay Project, a research group on campus that studies ways to solve problems.

An estimated 50 students each academic quarter are homeless at the Catholic university, where tuition is about $40,000 a year. Those who lose their housing because they are failing academically or falling behind on tuition and fees couch-surf or live in cars, Bombard says.

Advertisement

The group Bombard put together found there are at least 15 factors that can lead to homelessness: for example, not knowing how to do long-term planning, having no place to go when the dorm closes over holiday breaks, or having to commute from unsafe neighborhoods. It also found a list of 11 resources that are essential for getting and staying out of homelessness, such as a work schedule that allows for internships or group projects outside of class as well as understanding how to interact with faculty and meet university expectations.

"There may be present a certain expectation, mental model, or image in the mind of faculty and staff of how a successful college or university undergraduate student will behave," Bombard wrote in an email. "However, today's college and university student population includes many types of non-traditional students, in particular low-income students who may also be working adults and young parents."

Students may have received scholarships and financial aid to cover tuition, but they may not have any resources for daily life.

"[A] significant learning was a definition of poverty that revolves around lack of resources and the instability in one's life resulting from that lack," Bombard wrote. "In addition to housing, many students also lack food, winter clothing, or even something as simple as laundry soap."

Lacking the basics also affects those who are homeless with addictions. Bland says many young people have moved to Colorado, one of the first states in the country to legalize recreational marijuana, thinking it will be easy to buy drugs. Then they run out of money.

"[Addiction] is just destroying people," Bland said.

Chicago Benedictine Sr. Karen Bland, left, in her office at Grand Valley Catholic Outreach in Grand Junction, Colorado, where she is executive director (Courtesy of the Benedictine Sisters of Chicago)

The local supply of affordable housing is low, but instead of building more, the local housing authority had to spend $2 million to renovate an existing housing complex because of meth use and manufacture in the apartments there.

'They've learned not to trust'

Those who are made homeless also lose something just as critical as shelter, food and hygiene opportunities, Hannah says: community.

"The power of community to transform and heal someone is astounding," Hannah says. "That's what they need. Sure, they could use a job, but they need love and connectedness."

And yet engagement can be hard with people who are homeless because they do not trust easily, Hannah says. "A lot of them have given up and resigned themselves to being homeless or couch surfing."

That's true even on a college campus, Bombard wrote. You cannot assume that if someone loses his or her dorm room or apartment, they have anywhere to turn.

"Not every college student today has a loving, supportive home to return to during academic breaks when university housing shuts down," Bombard wrote. "For example, the student may come from an abusive, or unaccepting family and choose not to return. Parents may have 'downsized' their own home and no longer have space to welcome back their young adult child."

A lack of connection can lead to homelessness in other ways, too.

"We found that at DePaul there are indeed many resources already in place to assist low-income and first-generation students," Bombard wrote. "However, what students themselves and staff told us is that often there are emotional and psychological barriers within the students that prevent them from seeking the help they need. Students may not have the self-confidence to enter an office and approach adult faculty or staff to ask for help. Students also may be too embarrassed to ask for help, from staff or other students. They may not want others to know their situation, perhaps until it becomes critical."

Safe Places in Louisville works hard to build and maintain those connections. There is an art corner and lots of puzzles — not just to give clients something to do, but to help them lower their defenses.

Hand-warmers sewn by YMCA Safe Place Services staff member Roan Head await their first use by the day shelter's clients in Louisville, Kentucky. (GSR photo / Dan Stockman)

"A lot of times, when someone comes in really agitated, you can say, 'Let's come over here and color,' " Hannah says. "Puzzles are a great way to calm down and then begin to talk and engage with someone."

Community also means helping clients navigate social programs.

"The systems are not really designed to help, in my opinion," Hannah says. "To get food stamps in Kentucky, you have to work at least 20 hours a week. We had a client who started going to college, and you think that's a great thing, but now they can't work as much, so they can't get food stamps. They put up barriers. ... They create systems that basically shame you for reaching out for help."

Her four years at Safe Place have given her a lot of sleepless nights, Hannah says, but they have also taught her much about God and herself.

"Where I see God most in this ministry is just by the connections clients experience when they start seeing the good in themselves," she says. "They've experienced so much in their lives. They have walls and moats around their heart. ... It shows me how important community is. It doesn't have to be your biological family. It can be your chosen family: the people who pick you up when you fall, who see the goodness in you, who model love and truthfulness for you."

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]