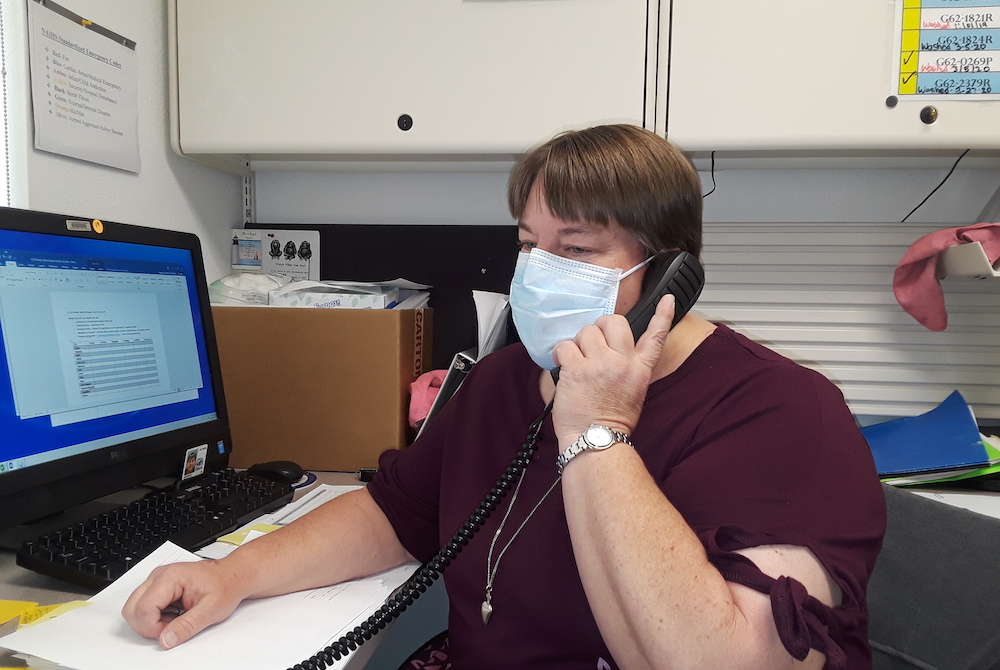

Sr. Michelle Woodruff of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ calls contacts of people who have tested positive for COVID-19 in April. She is a public health nurse at Crownpoint Health Care Facility in New Mexico. She made more than 50 phone calls that day. (Courtesy of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ)

Sr. Michelle Woodruff works as a public health nurse at the Crownpoint Health Care Facility, about two hours northwest of Albuquerque, New Mexico, and an hour east of the Arizona border. Her main duty in recent months has been doing contact tracing of people with coronavirus.

Woodruff had worked at this health care facility in Crownpoint for more than a decade until mid-July 2020 when she resigned because she received a new assignment as formator of her congregation, the Adorers of the Blood of Christ. However, her plan for further study in formation work was postponed until the spring 2021, so in late October she returned to the health care facility to work part time.

Woodruff spoke with Global Sisters Report about public health work, the coronavirus situation and healthcare disparities. Crownpoint has a population of 3,000. However, more than 20,000 patients use the Crownpoint Health Care Facility because it provides many health care services in an area covering 4,200 square miles. The facility comes under the purview of the Indian Health Service, the federal health program for American Indians and Alaska Natives, under the Department of Health and Human Services.

In May, the Navajo Nation had the highest per capita coronavirus infection rate in the country, and as of Dec. 1 had 16,711 cases of COVID-19 and 656 confirmed deaths from a population of about 175,000. Jonathan Nez, president of the Navajo Nation, cited several reasons for the large number of cases, including multigenerational living — parents, children and grandchildren — in one home: If one person gets the virus, others in the family risk getting infected. Another reason is the lack of water; Nez says that about 30% to 40% of the population have no access to clean, safe running water, which hampers proper hand washing. With few grocery, convenience stores and gas stations in the reservation, people congregate at the same stores to buy food. Social gatherings in the spring also helped spread the virus. The Navajo Nation for months has enforced strict daily and 56-hour weekend curfews to help prevent the spread of the coronavirus.

Woodruff, a native of South Hutchinson, Kansas, made her final profession in September 2010. She graduated from Bethel College, a small Mennonite college, and has been a nurse for 25 years. Amid the reality of health and socioeconomic disparities that she faces each day in her ministry, Woodruff said she has learned from the Diné (Navajo people) who are her coworkers, and the faithful of Crownpoint-St. Paul Catholic parish.

Crownpoint Health Care Facility, Crownpoint, New Mexico (Michelle Woodruff)

GSR: Please tell us about the public health ministry at the Crownpoint Health Care Facility.

Woodruff: Overall, the pandemic really highlighted the health disparity that exists in the Indian country and many other socioeconomic areas, but especially in the Indian country. We are already short on staff and supplies, so when something like this [the pandemic] happens, it really shows what you are lacking. The Indian Health Services did their best to get the staff at the hospital where I worked the resources we needed to do the work that we could.

The number quickly grew in March and April. The virus spread all over the Navajo Nation and here in the Crownpoint area. It was so unpredictable and spread so quickly. We didn't have the resources at our rural hospital to provide the care that they would need once they were diagnosed with coronavirus, as they showed significant symptoms like shortness of breath. We don't have [an] intensive care unit … so it was a lot of moving people from here to outside facilities.

Then there is a public health response. This is what I was more involved with because I am a public health nurse. We were trying, from the very beginning, to get people to wash their hands, to practice social distancing, to not gather in groups or meetings. We asked people to wear masks as they become more readily available.

We also carried out contact tracing for all the cases in our area. We called and followed up with those patients and their contacts every day for 14 days. The work was fairly intense plus trying to do the epidemiology pieces of the coronavirus, like the numbers of people infected and the severity of each case. We try to figure out what is the best approach: When do we need to get the people to come in to be seen so they would not get any worse at home, and also to see what support that they needed.

Sr. Michelle Woodruff of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ (Courtesy of Michelle Woodruff)

The access to water is an issue: If you are not able to wash your hands as well as you could because you don't have water at home, that is the issue. Then there are other issues, like what about hauling water for livestock? Going to town to shop for food supplies and risk being exposed to the coronavirus? Do you have electricity to be able to refrigerate your food? Have you lost your job, or has the person who is the main source of income lost his or her job? Are you able to get to the bank to get your money? For those in low socioeconomic levels, all those factors play into the pandemic tremendously.

So it was us trying to figure out, too, what resources were needed and how we could them get to the people. Do they need cleaning supplies? Do they need food? Do they need water? How could we get them those supplies that they needed? We work with a number of organizations, not only in-house services, like the Chapter Houses [administrative and meeting placed of each area], of the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation community health representatives were a huge asset for us to get supplies as needed.

Then we still have to keep the hospital going for normal activities. People still have dental emergencies. People still have eye emergencies. People still have other health problems that need continuing care.

Do people come in during the pandemic?

They are now. It was pretty limited in the first few months. Since mid-May we have been trying to increase more services. Now they [Indian Health Service] are trying to push for us to distribute the flu vaccine. That's a big push — not only for the flu season, but hopefully also in preparation for whenever the vaccine for coronavirus is available. It will help prepare us to do well and effectively.

Advertisement

Some dogs walk around the desert of Crownpoint, New Mexico (Michelle Woodruff)

How many beds are there in your hospital?

We have 12 beds but only for non-acute patients. The beds are only for patients with mild illness that need to stay in the hospital here. Otherwise those with COVID-19 will be best off in Albuquerque, Farmington, Gallup, and Phoenix — depending on the beds [available].

Could you talk about health disparities?

Being out in the rural area is a major health disparity. For anybody in rural America, access to health is very difficult. You have family practitioners that are there, but you have to travel one, two or three hours depending on what specialty of care you need.

The availability of transportation to get to an appointment is a problem. Not all people have cars. The lower socioeconomic level can contribute to the health disparity. People have to wait to get seen, but when things are bad, they have to call the ambulance.

The other health disparity is the lack of continuity of care. When you go to see a doctor, you think it is going to be your primary care doctor that you saw three months ago. When you get there, you find out your doctor has been changed. You have to start all over again for another doctor. Out here people talk about having to re-tell their story every time they go to the doctor.

Then on the prevention matters — how to eat healthy, how to keep yourself healthy by exercising — those kinds of things also factor in the health disparity. When you are constantly thinking about how to keep the roof over your head, whether you have enough food, or your kids have what they need, like food and shelter, or if you are safe, or if you have water to drink — when those things are your concerns, health does not fit very high in priority.

How do you keep yourself balanced or spiritually filled?

Besides our community, friends and those we know who support us, the Navajo people themselves. How could you not? They are filled with faith and spirituality. My coworkers are more spiritual and faith-filled than I am. I feel renewed through them. Then the parishioners here [St. Paul church] — they are amazing people. Just to be in their presence and listen to their stories is quite amazing. Of course, the beauty out here always sustains me. Going out for a walk or looking out the windows, you will always see the beauty of God's creation.

The high desert of Crownpoint, New Mexico (Michelle Woodruff)

[Peter Tran is assistant director of the Redemptorist Renewal Center in Tucson, Arizona.]