Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago addresses migrants at the Migrant Ministry of the Catholic Parishes of Oak Park's first location at St. Catherine of Siena-St. Lucy Church in Oak Park, Illinois, in a December 2023 photo. Program organizer Celine Woznica is pictured at right. (Courtesy of Migrant Ministry)

When Chicago native St. Joseph Sr. Jackie Schmitz volunteered to help at Migrant Ministry of the Catholic Parishes of Oak Park's "free stores," she knew it would be an emotional endeavor; but nothing could have prepared her for the story of a migrant mother holding her exceedingly thin 20-year-old son. "He looked to be about 10," Schmitz said, "because he had cerebral palsy."

The woman had not only carried her son via public transportation some 20 miles from the South Side of Chicago to reach the distribution center, but she had also carried him from Venezuela through the treacherous, some 60-mile stretch of Panamanian jungle known as the Darién Gap.

A 13-year-old confirmation candidate named Alec was at the center that day, distributing toys to migrant children. He found a collapsible wagon, fitted it up with a sleeping bag and a pillow, and helped the Venezuelan mom place her son in the vehicle. She would not have to carry him on her back anymore. When Alec asked her son's name, this valiant woman looked at him, and said simply, "Jesus."

In 2022, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott began busing migrants to the city of Chicago. By the summer of 2023, Abbott had been busing about 2,000 migrants a week to Chicago, according to WTTW. The arriving migrants included families from Venezuela, Colombia and Ecuador, who had walked to the U.S.-Mexico border, fleeing conditions such as repression, political violence, drug cartels and extreme economic deprivation afflicting their homelands. Many arrived with little to nothing.

Chicago volunteers hurriedly organized tent cities for migrants; the tents are pictured in the summer of 2023. (Courtesy of Migrant Ministry)

Chicago's shelters were quickly overwhelmed, so migrants were crowded into lobbies, along sidewalks and even in the parking lots of Chicago police stations. A group of volunteers — calling themselves "police station response teams" — quickly organized via a local WhatsApp group.

Enter Celine Woznica, a returned Maryknoll lay missioner who joined a team helping migrants at a police station two blocks from Chicago's Oak Park border. Woznica convinced her pastor to open a vacant rectory so the migrants could take showers. She and other volunteers found tents to protect them from the elements as well as meals, blankets, sheets, air mattresses, clothing, toiletries and shoes.

A migrant mother and her child shop for much needed clothing at a Migrant Ministry "free store." (Courtesy of Migrant Ministry)

From this tumultuous beginning, the all-volunteer Migrant Ministry was formed. And here's the kicker: according to Woznica (who describes herself as "older than the pope"), 95% of the over 500 volunteers are senior citizens. She said, "The whole migrant ministry is completely run by volunteers. There's not one paid staff member."

Woznica is even prouder of the interdenominational nature of the ministry's donors and volunteers. "They represent all the major faith centers in our area [Christian, Jewish, Unitarian, Muslim, and Baha'i]" she said. "And many who do not profess to any faith, consider the ministry their 'church.' " To date, the Migrant Ministry estimates it has touched the lives of some 15,000 people via its food, clothing, shelter, language and legal services.

Celine Woznica and her husband Don are leaders in the program. The couple served as Maryknoll lay missioners in Nicaragua and Mexico from 1981-1992. When they returned, they raised their family while continuing to be involved with immigrant and refugee populations.

In addition to services offered at Centro San Edmundo (or St. Edmund Center, the migrant center), volunteers at the Migrant Ministry support a special Housing Ministry which began in the fall of 2022. Margie Rudnik leads this program. After retiring from an organization she founded that served prisoners, Rudnik put her MBA and management skills to good use by developing a team of mentors to accompany migrant families as they find housing, acclimate to U.S. culture and work toward independence.

Advertisement

Always, migrants are eager to find employment. But this cannot happen, said Woznica, until 150 days after they submit their asylum application. Only then can they apply for a work permit, which usually takes another month.

Both Woznica and Rudnik relayed horrific examples of why migrant families are eligible for asylum. After gunshots riddled his home, one Venezuelan lawyer who had exposed corruption in the judicial system was forced to leave. Outspoken Venezuelan labor organizers fled with their children after receiving threats. When one Colombian family was threatened by drug cartels that wanted their land, they were forced to flee the coffee plantation that had been in the family for five generations.

Half of the 23 families currently served by the Housing Ministry were referred from Catholic Charities, but the Housing Ministry receives significant interdenominational support.

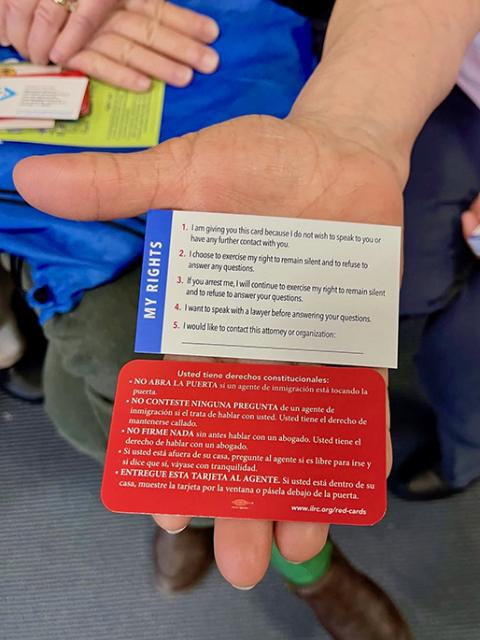

"Know your rights" cards in Spanish and English provide migrants and mentors with legal information about their right to due process. (Courtesy of Migrant Ministry)

Though Chicago is a sanctuary city, the Trump administration is ramping up deportations by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE. According to Woznica and Rudnik, some parts of the city with larger populations of immigrants have been experiencing raids.

But the Migrant Ministry is vigilant. The program is focusing on preparedness and support, and has created a rapid response plan in case ICE comes to Centro San Edmundo. Everyone is made aware that ICE cannot enter without a judicial warrant signed by a judge. An ICE administrative warrant does not permit legal entry.

The center is making sure every migrant completes and submits an asylum application form and distributes "know your rights" education and cards in Spanish and English to migrants and their mentors.

Volunteers tell Woznica: "I am so angry about what's going on in the treatment of the migrants. This is something that I can do. I don't speak Spanish, but I can sort clothing. I don't speak Spanish, but I can smile."

St. Joseph Sr. Jackie Schmitz (far right) joined other Sisters of Sr. Joseph at an El Paso border witness on March 2, 2024. Sr. Nina Rodriguez (far left) walks with difficulty but was determined to attend because both of her parents were undocumented. Schmitz, a Chicago native, volunteered to help at Migrant Ministry's "free stores." (Courtesy of Congregation of St. Joseph)

Others say their experience brings them joy: '"It gives me purpose. It gives me meaning. I'm part of something bigger." Rudnik tells me, "What I want to keep stressing is that the migrant families are so grateful. It doesn't make any difference what you're doing for them. They just sort of light up. And it's really gratifying," Rudnik said.

"They are incredibly faithful people," Sister Jackie said. "They're so religious and resilient when you think of what they're facing."

Perhaps Woznica sums it up best. "I feel like I walk among giants. I'm in awe of [the migrants'] resilience. They embody hope … and I think that's true for us too, because with every asylum application that we help fill out, or every set of new baby clothes that we assemble, with every family that's resettled, it embodies hope. The migrants tell the same story as our ancestors."