In September 2019, Salvatorian Sr. Jean Schafer, second from right, attended the 10th anniversary of Talitha Kum, the international umbrella network for sisters in anti-trafficking. (Provided photo)

Sitting in a comfortable chair at Barnes & Noble in 2002, Sr. Jean Schafer skimmed a stack of computer books, trying to pick the best one to teach her basic skills for designing a website and newsletter.

The Sister of the Divine Savior had just returned to the United States from living in Rome for 12 years, where she served on her congregation's generalate, and now found herself without an immediate ministry. But Schafer did have a new interest: anti-trafficking work.

After being introduced to the phenomenon of human trafficking when attending a talk in 1998, Schafer participated in the "worldwide discussion" in 2001 with the International Union of Superiors General on the exploitation of women and girls. UISG then released its first public declaration, calling on religious women to work on behalf of this vulnerable population, particularly within human trafficking. Congregations, including Schafer's, began making this a mission focus.

Back in the United States, "my idea was to get the word out," Schafer said. "So I just made a resolution: I'd try to put something out every month and see what happens."

Now, with her final issue in December 2019 behind her, Schafer has stepped back from her newsletter after 17 years, handing it off to editor Felician Sr. Maryann Agnes Mueller and designer Felician Sr. Mary Francis Lewandowski. Schafer instead will be focusing her time on various anti-trafficking commissions and coalitions.

GSR: Tell me how you decided what went in the newsletter as well as the process of putting it together.

Schafer: Every month, I'd pray that I'd find something online. My goal was to create a theme in every issue and build the information around that theme relative to awareness-raising information, some kind of advocacy for people who are victims of trafficking, and, finally, the action phase: What can you do to push this forward?

In the beginning, I was like, "Oh, my gosh, will I find anything online?" And then, 17 years later, the prayer is, "Oh, my gosh, of everything that's out there, what will I feature?" It could be book form at this point.

Advertisement

The original purpose of it was to help people learn about it. How it continues now is to provide a convenient resource so that someone can further share that information. The newsletter at this point saves people the time of looking that information up. It's like your monthly ready-reference on trafficking on youth, or forced marriage, or the selling of organs, or labor trafficking in the Middle East, or all the themes that emerged over the years.

How have you seen the issue evolve in the U.S. since getting involved? Have changing presidential administrations affected it, whether directly or indirectly through relations with Central America or women's issues, for example?

With each president's administration, through input from nonprofits and social service agencies and so forth, they became more aware of how prevalent it is in the U.S., as opposed to people saying, "Oh, yeah, that's in Thailand."

Secondly, I think the realization that a dark web is influencing a lot of what people do online — this is, particularly now, something that a lot of people, parents and government agencies are aware is affecting youth. The whole phenomenon of pornography is driving trafficking because it lures young people. They become addicted, and then they search ways to act this out with their relationships or strangers.

Salvatorian Sr. Jean Schafer, center, with Pope Francis and Franciscan Sr. Marlene Weisenbeck. Some sisters from the U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking coalition met Francis in 2013 when he held his first meeting on human trafficking at the Vatican. (Provided photo)

Another is the labor trafficking phenomenon. A lot of people who are in the U.S. who aren't immigrants and are working legally are also being exploited through either forced labor or violations of labor laws where people are not paid properly, or they're threatened, or their documents are taken, all these kinds of things. That's a whole area that needs much more awareness-raising and action.

Another interesting thing that has evolved is that different businesses have become aware of how they can help in the anti-trafficking movement. There's Truckers Against Trafficking, the guys that are driving semis around, at truck stops observing, and if that activity is going on, they know how to report it. Hospitals are very involved now because people are coming to the emergency room either with physical or sexual trauma and health issues, and the staff know the red flags, so they can often help someone who can't say anything, and they can find help for them. Same with hotels — a lot of hotel staffs and cleaning staffs are aware of red flags when they go into the rooms to clean and in checking people in and out.

One of the legislative dimensions is taking on demand. They have what's called the Nordic law in Sweden that came in the 1990s, where instead of arresting the woman for prostitution, they arrest the man buying sex, and they provide help to the woman. They cut their forced trafficking and prostitution in half. A lot of countries have taken that up. Here in the U.S., it's not federal yet, but a lot of individual states are looking at it.

Is that the legislative solution, if there were one, that you see being the most effective, as opposed to legalizing prostitution? What in your research, like the Nordic model, has caught your attention?

Legalizing prostitution would be a disaster. Scandinavian countries and the U.S. have done studies on the effect of legalizing prostitution, and what happens is it becomes a real business. But the women involved — and it's usually women — they are not generally the citizens. They are the people smuggled in or lured in from other countries, because even though you're a so-called legal prostitute, you have to pay taxes, you have to have health checks, and all this and that. There's a lot of red tape to be legal. So the legalizing of prostitution actually undoes the effort to diminish human trafficking. It increases it.

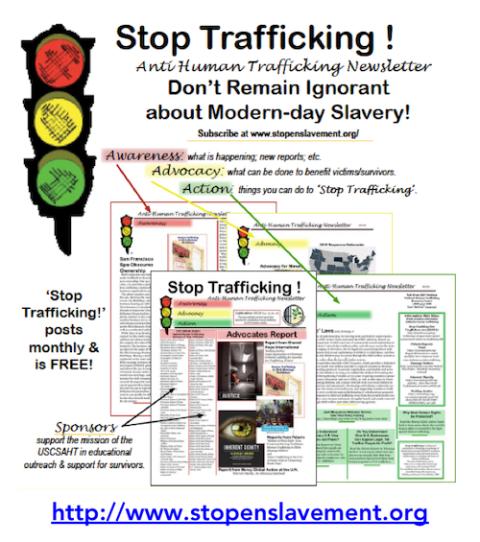

An advertisement for Salvatorian Sr. Jean Schafer's anti-trafficking newsletter (Provided photo)

Why did now feel like the right time to retire? What's the plan for having the newsletter continue?

I never like to hear the word "retire."

We'll call it "stepping back" from the newsletter.

I handed it on not because I didn't want to do it anymore, but many people said to me, "Jean, you need to update your website," or "You need to get into more social media; you should be sending it out on Twitter," and this and that. And I just don't have the time to be that committed to making it 100% modern. I started thinking I should hand it over to the U.S. Catholic Sisters Against Human Trafficking coalition, and maybe there's a member within that coalition who has the capacity to bring it up another grade and make it more modern, a little bit more out there in the mainstream.

Has being involved in this ministry influenced your prayer life or your outlook on spirituality? Tell me about the deeper, personal side effects.

Going all over the world and seeing the poorest of the poor was the first real conversion step for me.

When our province managed a safe home for survivors, another sister and I lived 24/7 with women who came out of human trafficking, both sex and labor. We've served about 50 women, and about 25 of them were from other countries. Living with them and seeing all the challenges that they've faced, trying to get back on their feet and trying to heal from this trauma — these kinds of things have really gone inside of me to a point where it's a real prayer preoccupation. I'm not thinking about the little insignificant issues of the day-to-day life. I'm so caught up in all the suffering of the world and the realization of how much people suffer through no fault of their own. They're just born into poverty, born into a desperation that puts them on the road to becoming exploited. They have no alternative.

My prayer life is completely transformed from what it would've been 30 years ago. I'm grateful for it, but I suffer from it, because sometimes, it looks very black, and I have to spend time praying to say, "Give me hope and confidence that we can turn this around." Thirty years ago, my issues were narrower; our community is very much Scripture-based, so I'd pray the readings of the day and see how it would apply to my life, but I don't think I reached out into the broader world as much. Now, I feel like I'm a voice for the voiceless, pleading that the Holy Spirit can help us shout out what really needs to be done in our world.

[Soli Salgado is a staff writer for Global Sisters Report. Her email address is [email protected]. Follow her on Twitter: @soli_salgado.]