(GSR graphic/Olivia Bardo, GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

To the beat of a drum and with her tender voice, Sr. Blanca Meza shared the story of Afro-Colombians like her with members of the V Latin American and Caribbean Congress on Religious Life.

"We are Afro-Colombians, we have an identity, we work very closely together for social justice. Our principle in life is to fight for equality, so that we can all live in brotherhood," she sang.

The song captures the spirituality of the Afro-Colombian world: "Who we are," she explained about the descendants of people who were brought to the Americas from Africa and now are part of Catholic religious life in Latin America.

Meza's experience as an Afro-Colombian religious woman is unusual, which is why she likes to share it, as she did with members of religious life at the end of 2024, even though it deals with painful issues such as the sin of slavery, discrimination and racism, but also with hope.

Hope, she said, lies in recognizing the mistakes of the past in order to heal deep wounds that exist among Afro-descendant members of the church.

"Who are we, Black people? Many will ask: Why do we see so few Black people in religious life? Why aren't there more Black religious men and women in communities? Who are we, Black people? We are people," she told religious men and women during a panel discussion at the gathering.

'I am surprised to see so few Black people in religious communities. This should be a call for reflection, especially for congregations.'

—Sr. Blanca Meza

Advertisement

Sr. Blanca Meza, of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Immaculate and Saint Catherine of Siena Congregation in Colombia, poses for a photo on Nov. 24, 2024, in Córdoba, Argentina. (GSR/Rhina Guidos

Meza, of the Congregation of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Immaculate and St. Catherine of Siena, recounted part of the history of how, between the 16th and 19th centuries, approximately 12 million Africans were brought to the Americas to be sold as slaves and forced to work in inhumane conditions.

"Through this process, our ancestors experienced countless tragedies and sufferings. Religion played a fundamental role in the lives of African Americans. Although they arrived in the Americas with their own beliefs and religions, they soon encountered a different reality," she said. "The Catholic Church, in its evangelizing zeal, took it upon itself to impose its faith on enslaved Africans, who were forced to adopt new beliefs."

This is a struggle that continues for African American members of the Catholic Church, she said.

"In our church and in our religious communities, we hope that the cry of our people will be heard spiritually. We need an inclusive church, not an exclusive one," she said.

"Why do I insist on this? Because in the past, Black people were not accepted in convents or religious congregations, let alone Indigenous people," she added.

Throughout history, Afro-descendants have been seen as a problem, as a burden, she said, and have been excluded, even within religious institutions.

"I am surprised to see so few Black people in religious communities. This should be a call for reflection, especially for congregations," she said.

In an interview with Global Sisters Report, Meza spoke about the challenges and opportunities for religious life in Latin America with regard to Afro-descendants and other groups.

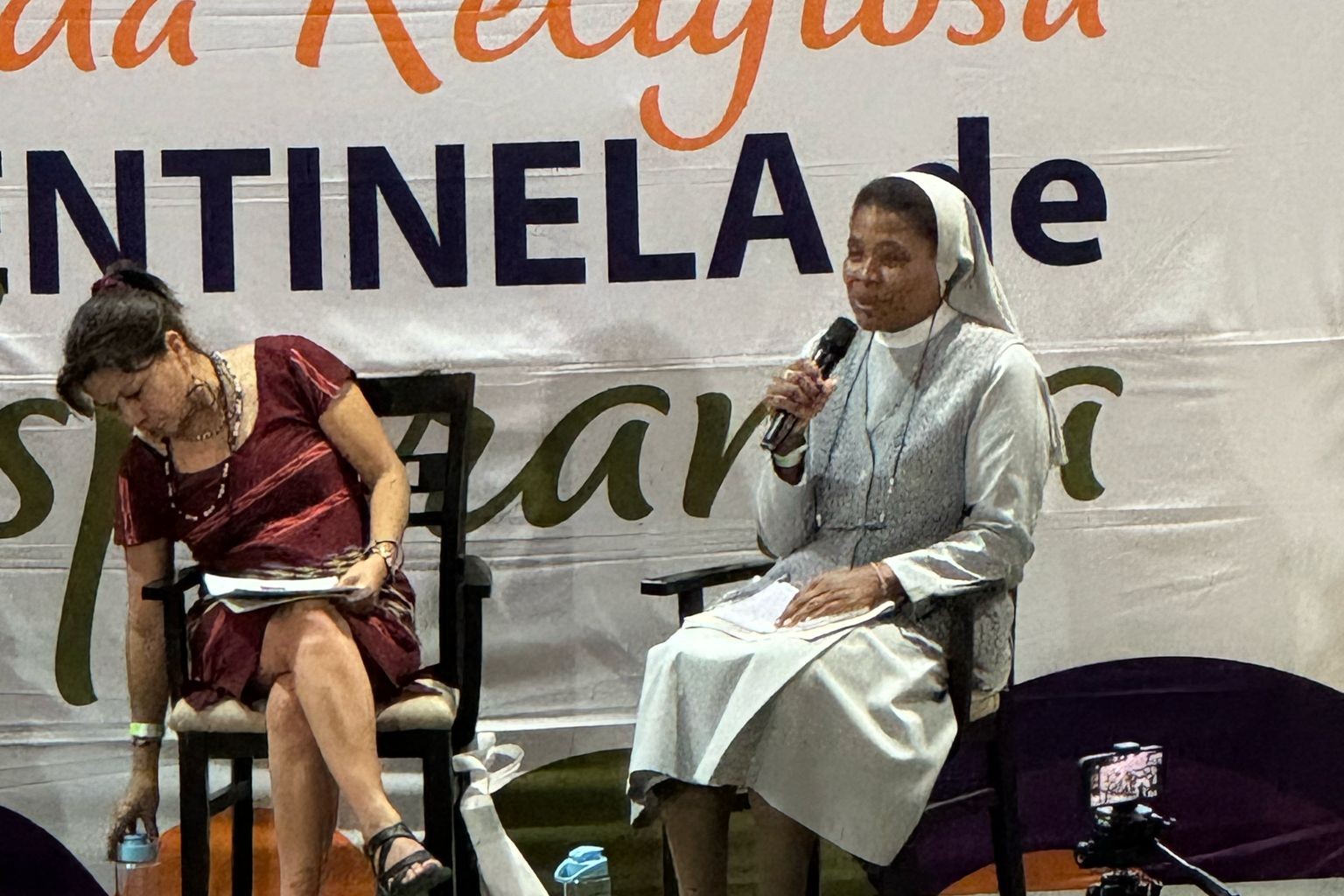

Sr. Blanca Meza, right, of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Immaculate and Saint Catherine of Siena in Colombia, shared the story of her Afro-Colombian people with members of the Fifth Latin American and Caribbean Congress on Religious Life in Córdoba, Argentina, on November 24, 2024. (Photo: GSR/Rhina Guidos)

'The church and congregations have to be inclusive, not exclusive, because, as always, historically, white people, colonialism, have prevailed.'

—Sr. Blanca Meza

Why is it important for the church to listen to these issues?

I think it is very important for the church, because at this moment we are sentinels of hope. The church has to open itself to that, open itself to truly giving that hope to people, so that the people can feel welcomed and can feel that atmosphere of hope, to be hopeful as well. So, I believe that the church has to take these steps, and these steps are being taken to the extent that they open themselves to listening to us, to letting us express ourselves and not judging us, but rather listening attentively to these cries in order to find the way forward. And, obviously, these paths have to be found together. As they welcome us and we interact, we share. Together we find those paths of how to give hope. And from our position as religious, we go out to give hope to others, because there are many, many people out there who are obviously desperate. So, by sharing and experiencing that hope, we can give hope to others.

You found hope to continue with your vocation, but tell me a little about the challenges of your experience as a woman religious.

When I entered the convent, as the years went by, I found companions in the sisters, that possibility, that it is possible to be religious even in the midst of difficult experiences. When I entered, I was the only Black person in the group. There were 19 of us.

I always felt I received certain looks, certain barriers. But something that helped me a lot, personally, was my attitude, because we, as Black people, are cheerful, we are, as we say back home, very outgoing, we don't sit still. So, that heaviness that I felt at a certain point, I transformed into joy, and I got so involved that in the end I felt that I was very loved by my companions.

In other words, I overcame that barrier. But there are other cases in which joy is not enough, nor is feeling part of the group, because there are certain things that make you take a step back. But thank God I've been in religious life for 24 years and I've been taking steps forward, and I feel that people have been taking steps forward, too. But it's still necessary. That's where we are, in the fight, so that what has been built up is not lost, but that we must continue, we must continue to pave the way.

Do you feel that from time to time some people feel uncomfortable with what you say, especially when you talk about racism?

Yes. I feel that these issues create, in a way, a sting in people... and that's why I say that the church and congregations have to be inclusive, not exclusive, because, as always, historically, white people, colonialism, have prevailed.

You hear terms like, "The congregation is going to 'be blackened.' " Those are very strong terms, but you say, "Those are ignorant expressions." We are not a separate piece; we are part of a whole that God created. That whole is simply made up of those different parts that form, as they say, a complete fabric.

They don't have to look at us as different people in every way, but different in culture, yet we are part of the whole. In other words, if they don't make us part of that whole, they are incomplete.

And what would you say to a young person who is interested in religious life but also sees the challenges that still remain?

What I tell them is not to be afraid, not to feel that fear of wanting to join but being scared because they are Black. Don't be afraid, you have to face it.

For example, yesterday, when I said, "It's a miracle that I'm here," it really is a miracle. At one point I thought about saying, "No, I'm not coming, I'm not taking this on," but I said, "We don't have to be afraid, we have to overcome that fear."

So don't be afraid, take risks, overcome all those fears. And from within, you can contribute to all these processes of teaching people, of showing them our reality and making them feel that we all have to be okay.

Sometimes certain types of authorities create fear so that things are not said or seen.

But thank God, one thing I am grateful for is that, at least, I see progress; there is some progress that allows people to express themselves, because before they couldn't. And that's why many people, many religious men and women, refrain from expressing their feelings, from saying things, because sometimes they feel alone.

This story was originally published in Spanish Aug. 7, 2025.