Pope Francis meets St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean, who has worked in prison ministry and against the death penalty for decades, after his morning Mass at the Domus Sanctae Marthae at the Vatican on Jan. 21, 2016. The pope asked Prejean about the case of Richard Masterson, a Texas man who was executed the previous day. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

No matter what Pope Leo XIV — or any future pope — does in regard to the death penalty, it seems none will have as great an impact as Pope Francis.

In August 2018, the Vatican announced Francis had ordered a revision of the Catechism of the Catholic Church to assert "the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person" and to commit the church to working toward its abolition worldwide.

With a stroke of the pen, the world's 1.4 billion Catholics became — officially, at least — against capital punishment with no exceptions. It seems improbable a pope would ever reverse that change.

"What it did was it gave us official teachings so we couldn't have bishops going against it," said St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean. "When we started, we had bishops in favor of it [the death penalty]."

Prejean's reference to "when we started" was more than three decades ago when she wrote her 1993 book, Dead Man Walking. She shot to national prominence when the book was made into a movie in 1996 starring Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn.

It has since sold hundreds of thousands of copies and been translated into 10 languages, and Prejean spends her time working to end not only capital punishment, but also support for it among those who call themselves people of faith — support that, for Catholics at least, is contrary to church doctrine, thanks to Francis.

Prejean said Francis' legacy on the death penalty will continue, whether Leo makes its prohibition a priority or not.

St. Joseph Sr Helen Prejean, who has worked in prison ministry and against the death penalty for decades, is pictured in St. Peter's Square, Jan. 21, 2016, at the Vatican. (CNS/Paul Haring)

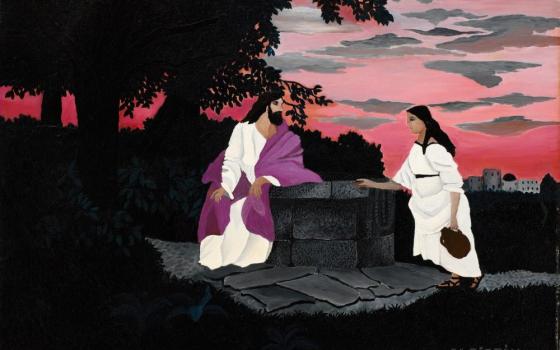

Global Sisters Report: You say Pope Francis not only changed church teaching on capital punishment, but that he got personally involved in cases, trying to prevent its use, including the case of Richard Glossip, who was served his "last meal" three times in Oklahoma, but the U.S. Supreme Court in February threw out his conviction and ordered a new trial.

Prejean: As soon as Pope Francis was elected, the first sign of hope was that he took the name Francis. And then his first act was to go to a prison and wash the feet of the prisoners.

Early in 2015, I got a call from Richard Glossip, who was very apologetic, saying, "I put you down to be with me when I die." I've been with men in eight executions, three were innocent. I began looking into Glossip's case and said, "This man is innocent." What do you do when you're asked to be with someone as they're executed and you know they're innocent?

I used a contact at the Vatican to get Francis to intervene. Pope Francis got word to the governor, "Don't kill this man."

Death penalty cases often take decades, but this one has had more twists and turns than most, including Oklahoma's attorney general, who is in favor of capital punishment, arguing Glossip should not be executed.

The very attorney general of the state recognized and admitted the state had made mistakes and Richard Glossip's constitutional rights were abused. He filed with the defense. Amazing. And when it really counted, Pope Francis was there.

Later, when I got to go to Rome, I took a letter from Richard Glossip thanking Francis. When I met him, there had been a man executed in Texas the night before, and the first thing the pope asked me was what happened in that case. I said, "Holy Father, he was killed." His face just fell.

Advertisement

You have said Francis' push for synodality in the church also influenced his actions on capital punishment. How so?

When moral things change in the church, it's because of dialogue. You can't have a decision from on high, it has to spring up from the people, there has to be an education process.

Dialogue is key. The death penalty took 1,500 years of dialogue — you can't turn the whole cruise ship around just by saying turn. The pope can only mirror the people — the church is defined as the people.

People are not wedded to capital punishment; they've just never contemplated it. But when you bring them close to it, show how it's done with human agency, mistakes and discretion, they're opposed.

Support for the death penalty continues to fall, but some officials seem to be executing people as fast as they can.

Now we see the pattern that's being enacted is a wave of executions in ex-slave states. In Louisiana, the governor wants to empty death row, like President [Donald] Trump did last term when he executed 13 people. It's part of their political agenda to show how they're tough on crime.

You've got to look at the deep racism of a state, because they've been given this power.

Is that increase in executions part of the pendulum swing we often see in politics, where any move in one direction is followed by a stronger move the other way?

It's not so much a pendulum as it is the way the Bible always talks about wheat and weeds coming up beside each other. Just like you have this crisis of pedophilia and abuse, and the people of God stepping up and living the Gospel.

It is slow change, but it is always change toward the better.