Sr. Jannette Pruitt and Archbishop Shelton Fabre of Louisville, Kentucky. Pruitt designed and created her dress, as well as Fabre's vestments. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

When Sr. Jannette Pruitt was a young child, she dreamed of becoming a nun. Pruitt, 76, recalls that friends she still has from elementary school remember her on the playground saying, "I'm going to be a sister, and everybody's going to call me Sister Jannette."

But that young girl's ambitious plan took years to materialize. It was the 1950s in the deep South. For years, the parish her grandparents attended was a "white" church — Black people who wanted to get married or have a child baptized had to do so in the choir loft. And while there was a seminary available for young Black men called to the priesthood, similar opportunities didn't exist for young Black girls.

Sr. Jannette Pruitt, 76, Sisters of St. Francis, Oldenburg, Indiana. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

"I was in third grade when Sr. Mildred asked what I was going to be as an adult, and I said 'Oh, I'm going to be a sister.'"

The declaration was met with a suggestion that the little girl also consider becoming a mom. Ultimately, that's exactly what Pruitt did. The marriage ultimately didn’t last — her husband ended up in prison, the pair divorced and Pruitt had the marriage annulled. But she’s a proud mother to three, a grandmother and great-grandmother.

Still, Pruitt grew in her faith thanks to her grandparents. She would walk to daily Mass each morning with her grandmother, who attended each day so she could be "pure and clean for the Lord." Her grandfather was part of the construction crew that built the now-historic St. Rose de Lima Parish, which has for decades served a largely Black congregation.

Her grandparent's home was the site of weekly after-Mass family gatherings, where the morning's take from the Gulf was served up in a gumbo that would be dished out and eaten wherever space was available. It was Pruitt's grandmother who taught her how to sew, when they would sit outside together on the house's large front porch.

A mitre designed and created by Sr. Jannette Pruitt. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

"She would tell me, 'Jannette, you ask too many questions.' But the one thing she would talk a lot about was her faith," Pruitt said. "My grandmother and grandfather were lovers of the Lord, of the faith, and that goes back generations before them."

And while Pruitt's dream was delayed, it was not denied. At 47, Pruitt decided to join the Sisters of St. Francis in Oldenburg, Indiana. It was there that her grandmother's teachings took flight in a way that her once-little-girl self could never have imagined.

Global Sisters Report: After raising children and working in health care, what made you decide to pursue your dream of becoming a sister?

Pruitt: At the urging of a friend, I had moved to Indianapolis and was an assistant at St. Rita's School with one of the teachers in kindergarten. I was there for two years, and in my second year, I got this urge, this calling. I was the kind of person … I did my Bible study. I would pray, pray, pray. And then I saw something in the bulletin about a life awareness weekend for anyone thinking about becoming a nun. I was in my 40s and hadn't thought about being a nun for decades.

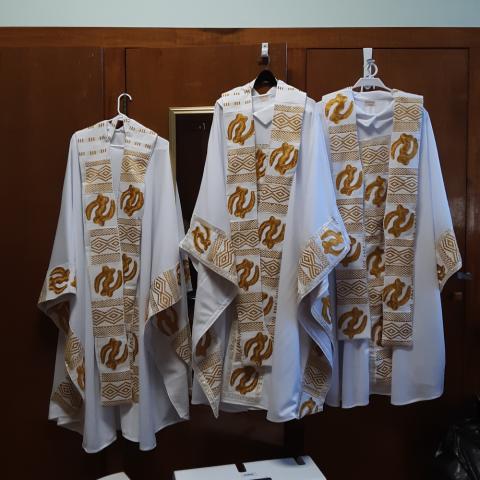

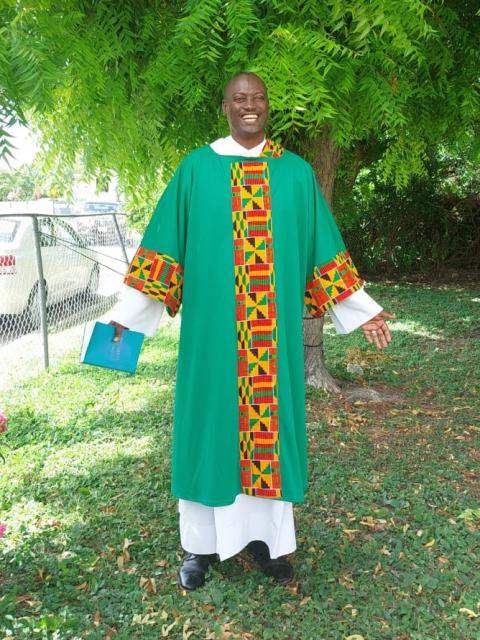

Vestments made by Sr. Jannette Pruitt that celebrate Afrocentric heritage. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

What happened when you started to think about it again?

I couldn't shake it. It was on my mind and heart and keeping me awake at night. In my writing (journal) I wrote, "What will you have me do?" And I just felt, I knew, I had to call the center (where the weekend was being held). I asked about the cost, and it was some astronomical amount of money, and I said, "Oh, well I can't do that, that's too much." And she said, "That's OK. We have a scholarship for you."

The moment I walked across the threshold (at the center) I felt something so deep. All the worries just went somewhere.

How did you land on the Sisters of St. Francis at Oldenburg?

An altar cloth designed and created by Sr. Jannette Pruitt. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

Sisters, priests, brothers were all lined up by order at these tables. They had the Sisters of St. Francis there, and I saw these grounds, it was so beautiful, and they had books showing sisters in community. Sr. Marge Wissman was behind me and said, "Why don't you come and see."

When I drove there, I missed the exit, stopped and called back to the motherhouse and somehow the Lord got me there. The sisters were so welcoming, they could not wait to talk to me while I was there. It was just like I was at home.

Did anything else tip the scales for the Sisters of St. Francis?

When I was talking to Sr. Marge, she mentioned the Nia Kuumba Spirituality Center in St. Louis (sponsored by the Sisters of St. Francis). I said, "You have a place for me?"

I drove to St. Louis and when I went through the door, I was home. There was a picture of Sr. Theo Bowman at the top of the stairs. Upstairs, there was a big Black doll on the bed, and over the bed, there was a picture of a little Black girl with beaded braids in her hair. I used to bead my kids' hair. Seeing all that and experiencing all that, I knew that this was my place to be.

Advertisement

How did you get so heavily involved in amplifying the work of Black people, especially Black women religious, in the church?

I think about it a lot. My responsibility is to encourage. The way it is in this world today, compared to the kind of way I was brought up, a lot of children don't have that experience. Because I've been at parishes, I've seen and worked with a lot of good families, and there's a lot of teaching that has to go on.

How did you get started celebrating your culture in your sewing?

A bishop's mitre created by Sr. Jannette Pruitt. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

I walked into church at St. Rita's one day, and (twins) Fr. Chester Smith and Fr. Charles Smith saw me. One asked, "Where did you get that outfit?" It was a dress, but the top had a cape to it and it was very colorful. I said, "I made it." And he said, "Well, you're going to make us some priest vestments." And all I could say in return was "Father?!"

But then you know I was designing and making vestments for different events. I've even made a mitre for a bishop! I made altar cloths, banners — I made banners with Sankofa birds. His head faces forward, like a swan, but his long neck turns around and he's looking back. Because we face forward to the future, but we go back from whence we came and bring all that knowledge forward into the future with us.

Talk a little more about the designs and colors you use in your pieces.

Vestments created by Sr. Jannette Pruitt. (Courtesy of Jannette Pruitt)

It goes back to family. My grandmother taught me how to crochet. My mother can sew things with her hand straighter than a sewing machine. It's in our family. I've used Adinkra symbols, like the Sankofa (bird) and the Gye Nyame, which represents God. All of the symbols mean something.

Why do you think this kind of representation is so important?

There are a lot of Black sisters and priests who get together to talk about what needs to be done for our people. I'm active in the National Black Sisters' Conference, and have been nominated for the Harriet Tubman Award five times.

I am in the church in a way that many others can't be, and God chose us. He saw us and understands all of what we went through. He's brought my people through a lot. We have to not just take and live our own experience, but we have to give it, to pass it on to the next generation so that they might understand.