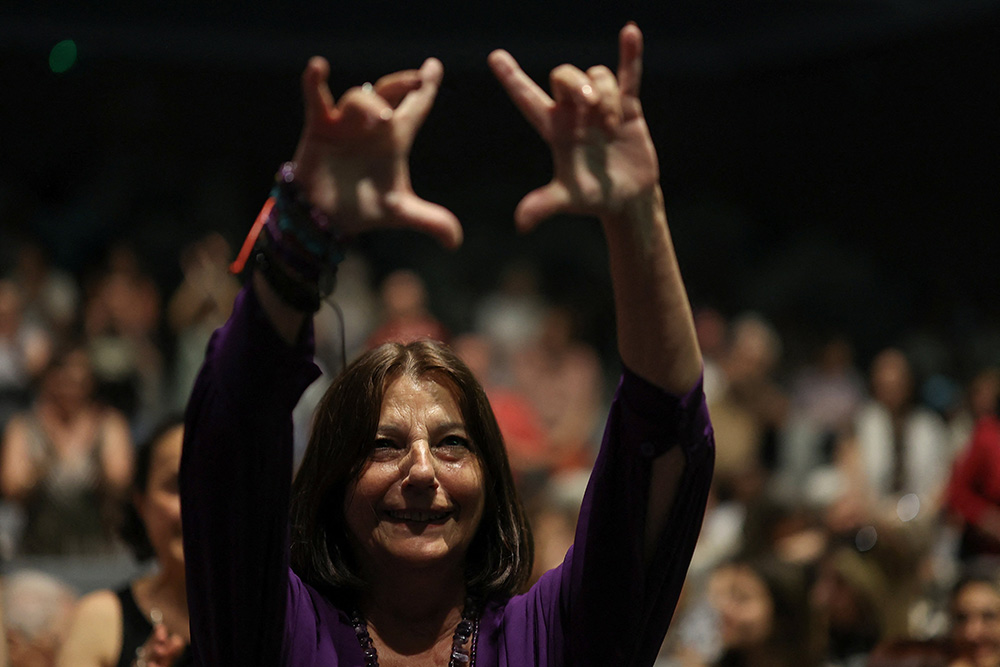

Consuelo Garcia del Cid, 66, a survivor and advocate for the cause, reacts before a ceremony in Madrid June 9, 2025, by the Spanish Confederation of Religious Entities to apologize to the survivors of Catholic moral rehabilitation institutes in Spain, where thousands of women and girls suffered harsh treatment during Francisco Franco's dictatorship. (OSV News/Reuters/Juan Medina)

Editor's note: This story is part of Global Sisters Report's yearlong series, "Out of the Shadows: Confronting Violence Against Women," which will focus on the ways Catholic sisters are responding to this global phenomenon.

(GSR logo/Olivia Bardo)

I couldn't hold back tears as I read the testimony of one of the survivors of Spain's Patronato de Proteccion a la Mujer. One line during her interview with El País pierced me like an arrow: "Forgiveness is forgetting."

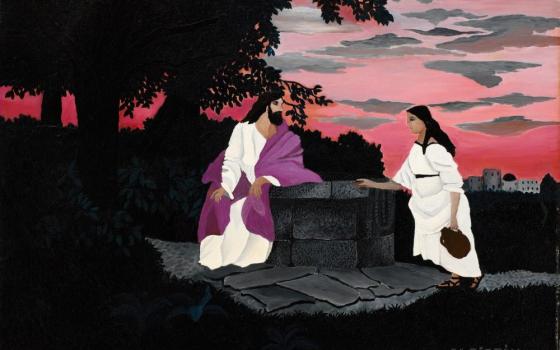

The Patronato de Proteccion a la Mujer — Women's Protection Board — was reinstated by dictator Francisco Franco's regime in 1941 and operated under the authority of the Catholic Church. Its goal was to "save" women deemed morally deviant: rebellious teens, single mothers, orphans, abuse survivors, or simply women that did not fit the era's definition of decency — or rather, what Franco's regime and the church determined as such.

Many of these women were confined in centers run by religious congregations where they endured years of confinement, silence, humiliation, forced labor and violence that left deep scars. The patronato continued operating even after Spain's return to democracy, nearly a decade after Franco's death. Even today, talking about what happened there remains painfully difficult.

Advertisement

On June 9, at Madrid's Fundación Pablo VI, the Spanish Conference of Religious (CONFER) held a public event to acknowledge and seek forgiveness from women who, as girls or young women, suffered humiliation, abuse and violence in institutions run by the patronato. The event had been planned for months: testimonies would be read, apologies offered and roses presented in memory of the victims.

But it did not go as planned. The women responded with a resounding "no," their decades-long anger spelled out in bold letters on signs.

Many survivors attended that day, rejecting apologies with cries of "Truth, justice, and reparation" and "Not forgotten, not forgiven."

Those cries slipped through the cracks of my own wounds. I wasn't there. I'm not Spanish. I don't belong to any of the congregations that ran those centers. I don't even share the same historical context. But I am a consecrated woman. And that is enough for me to feel some of the weight of that institutional responsibility. The church isn't just history. It's also a body. And I am part of that body. I chose to be part of an institution that, while it has given me much, has also hurt me.

That's why I understand the refusal. Because when the wound is inside — in what was believed to be sacred, untouchable — forgiveness becomes fragile ground. Forgiveness is expected and even idealized. But it is seldom accompanied. It is assumed that those who have suffered should have the capacity — and the christian obligation to forgive. As if it were that simple. As if forgiveness were merely a rational decision and not a struggle that emerges from deep within, wreaking havoc in the stomach, making the whole body resist.

Those who haven't been hurt in this way would never understand that sometimes, forgiveness hurts more than the original offense, especially when it is requested without addressing the underlying wounds.

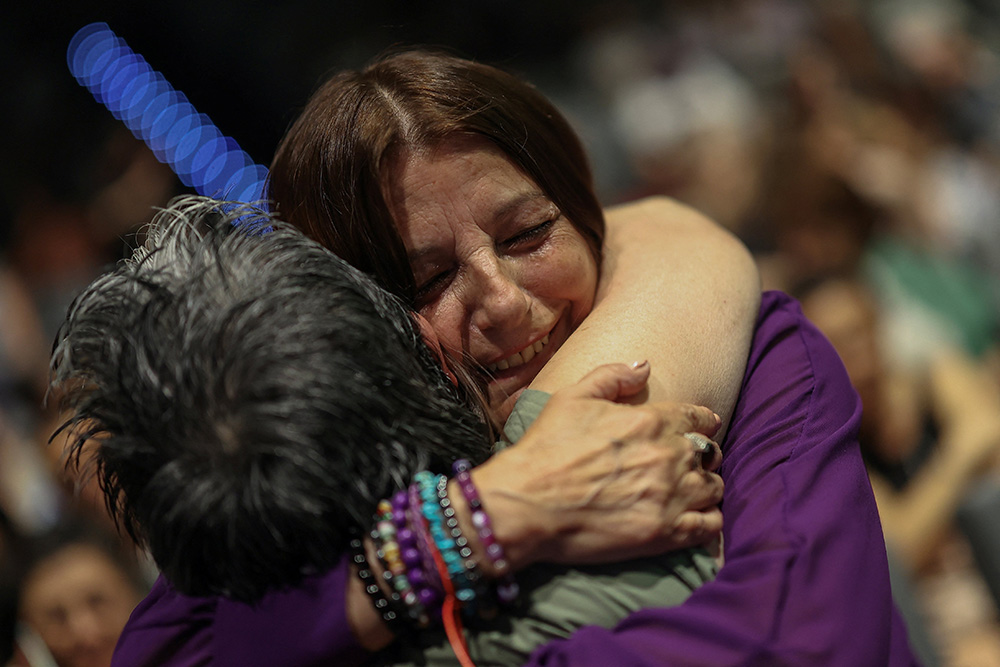

Consuelo Garcia del Cid, 66, a survivor and advocate for the cause, hugs an assistant before a ceremony in Madrid June 9, 2025, by the Spanish Confederation of Religious Entities to apologize to the survivors of Catholic moral rehabilitation institutes in Spain, where thousands of women and girls suffered harsh treatment during Francisco Franco's dictatorship. (OSV News/Reuters/Juan Medina)

The Spanish Conference of Religious took an important step that does not erase the past but it looked it in the eye. I saw it as a difficult, sincere and humble gesture. It was an act of institutional accountability — rare, and desperately needed. This first step may not change anything right away, but it could mark the beginning of something. I believe their intent wasn't to bring closure to a process but to initiate one.

Still, I understand that not everyone could receive that apology. Not all wounds are the same. Some survivors might need different responses first: legal recognition, opening of archives, deep listening. Others might need to tell the stories as many times as necessary — not only of what happened in the centers but how it shaped their lives afterward. Because they are owed more than apologies. They are owed possibilities.

I keep praying with the woman's words: "Forgiveness is forgetting." And from my own vulnerability, I dare to say no. Forgiveness is not forgetting. Some things should never be forgotten.

Forgiveness is sometimes described as releasing the other person from guilt. But often, it's about freeing oneself — refusing to let the harm inflicted become a root of bitterness that continues to grow inside. Forgiving does not mean forgetting, justifying or reconciling. It means not perpetuating, on one's own, the suffering inflicted by others. Because if it is not healed, the damage continues to govern emotions, decisions, even relationships with others.

Forgiving does not mean forgetting, justifying or reconciling. It means not perpetuating, on one's own, the suffering inflicted by others.

Forgiveness does not imply restoring a relationship with the one who caused harm. Not every bond should be restored. Not every wounded person can learn to trust again. And that does not weaken forgiveness.

And that does not mean everyone is ready to forgive or that they should. If forgiveness comes, it must be a completely free decision. It will not erase memory, but it can stop pain from continuing to dictate its story.

But forgiveness does not come through pretty words. It comes through justice, patience, humility. Through bent knees. Through open archives. Through long listening. Through individual repair for each woman.

One of the women said of the centers, "God was not there." I do not have any answers, only the certainty that the Spirit moves even among ruins. That there is no wounded body where God does not want to dwell.

I hope that what happened is never forgotten. I hope the memory of such painful acts helps us shape a religious life that is more human, more free, more faithful to the Gospel we long to live.

May forgiveness come when it needs to come. If it ever does. In the meantime, may the truth never be missing. May listening never be absent. And may no one ever doubt God's presence wherever we are.