"Francis Preaches to the Animals," a 1956 piece by Carl Wyland, was removed from the 1916 motherhouse prior to its demolition and placed on the façade of the new motherhouse. (Jean Molesky-Poz)

On the first Sunday in October 2019, my friend Jane Clare and I headed to the St. Francis Convent on South Lake Drive in Milwaukee to celebrate the feast of St. Francis with the Sisters of St. Francis of Assisi. As we pulled onto the grounds, Jane Clare slammed on the brakes. The scene before us looked as if a bomb had hit. The motherhouse of the oldest Franciscan congregation founded in the United States was under demolition.

Mounds of rubble covered the parking lot: slabs and chunks of concrete, broken bricks, twisted rebar. The powerhouse with its tall chimney, the laundry and the bakery — all had been leveled. Here and there in the ruins, we saw an opening into what had once been a system of underground tunnels where lines of novices had carried baskets of laundry or fresh-baked goods from one building to another. Beyond the heaps of debris stood remains of the motherhouse. Pipes dangled. Plastic sheeting fluttered in window frames.

The Sisters of St. Francis continue to prune and maintain the congregation's grape arbor, which was added to the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, grounds in 1912. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Francis)

I looked up at the third floor, where the postulate had been, where we had been introduced to religious life. There, we had slept in a dorm, each with her own "cell," furnished with a bed, nightstand and tin washbasin, separated from the others by thin yellow curtains. There, we intently listened to instructions for our new life. That place, now gone, is where I had met Jane Clare and 17 other girls who entered the Franciscan community in 1965.

Even though the old building no longer met the congregation's needs because of safety and other inadequacies, I still felt a deep sadness in seeing the ruins. A small band of lay third-order Franciscans, six women and seven men, including two priests, came from Bavaria in 1849 and settled on the south bay of Lake Michigan to minister to German immigrants in North America.

The community had a rocky beginning: The six founding women grew exhausted and disillusioned with duties at the convent and the newly founded orphanage, as well as the domestic chores at the seminary — milking the cows, scrubbing laundry on washboards, hauling water from a pump, cooking for the seminarians — and left. Others stayed, more joined, and over time, a formal religious life was established.

A two-story brick convent was built in 1861. A Gothic chapel, with 30-foot-tall, gold-leaf ribbed pillars and vaults, hand-carved altars and stained-glass windows imported from Europe, was dedicated in 1895, paid for "by imposing strict poverty on the sisters and asking for donations," wrote Franciscan Sr. Mary Eunice Hanousek in A New Assisi, which chronicled the congregation's first 100 years.

The beehives on the Sisters of St. Francis' grounds in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Francis)

Additions to accommodate the growing community were built in 1888 and 1916. Many girls entered the front doors of the motherhouse, eager to love and serve God.

More than 1,600 women became professed sisters; many others left as postulants or novices. Yet all shared this "mothering" space of formation for at least a few months or years at an important time in our lives. In the chapel, we prayed the Divine Office three times a day, attended Eucharist daily, meditated on Scripture, and shared our blessings and challenges privately. We learned to live with other women, to appreciate our gifts and differences, to reconcile, to get along. In silence, we found an interior depth to tend to the mystery of God. There were also rules and regulations that could be survived with a good sense of humor and creativity, or lead to departure.

By the time I entered the convent, the Second Vatican Council had introduced mandates for renewal in the Catholic Church and in religious life to meet the needs of the modern world. Through a college education, we were prepared professionally to serve others with love. In the last decades, religious women have been living into a new understanding of religious life: seeing their ministry as service, but also as prophetic. I didn't sense that part of our role when we were in the novitiate.

Of the 19 of us who had entered together in 1965, all but three left the convent.

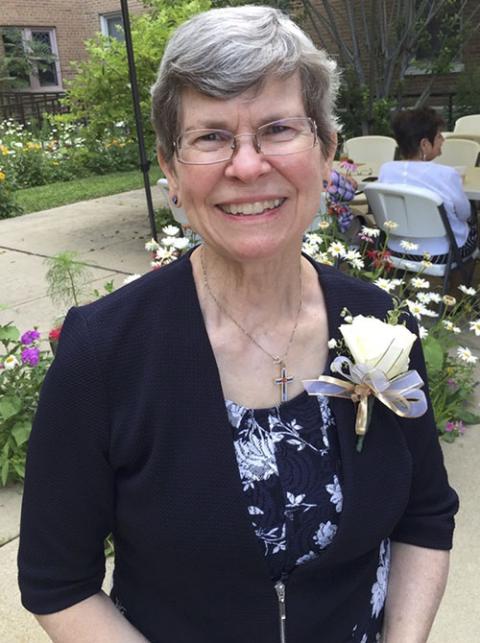

Franciscan Sr. Diana Tergerson (Jean Molesky-Poz)

New motherhouse, same Franciscan spirituality

I returned to the demolition site a week later to find more than half of the motherhouse gone. Sr. Diana Tergerson, the congregation's secretary, who had been a classmate of mine, accompanied me. We watched a hydraulic excavator crawl up a mountain of rubble, stretch its dipper and topple remaining walls. Window frames fell. Another excavator dug into a heap of rubble, opened its claw, grasped a metal pipe, swung around, and tossed the pipe into a pile of scrap metal.

Diana pointed to three men sorting through a mound of light-yellow bricks, Cream City bricks, made of clay from the shores of Lake Michigan in the late 19th century, stacking the good ones onto a pallet to be wrapped in plastic and resold. Copper wires lay in a dumpster for recycling. Already, Habitat for Humanity had salvaged doors and windows, furniture and lamps for construction projects in Milwaukee's poor neighborhoods. At least, I thought, much of this would be useful for others.

Diana and I talked of the works of art in the Gothic chapel — a physical touchstone of the sisters' identity, the space of daily Mass — of religious professions and of funerals during the past 124 years.

"I look at this as similar to someone donating their organs after death," she said. "The hand-carved altars, the stained-glass windows, the statues, the oak pews will continue to give life to other people and be appreciated for their beauty."

Advertisement

Listening to Diana, I began to see the scene before us differently. The motherhouse was not being demolished, but deconstructed. Building components were being selected for reuse or recycling and the waste managed with consideration for the environment.

This community's religious life is also being deconstructed. It remains one of prayer and service, exemplified in the sisters' lives and ministries and in the quiet way they keep vigil with each dying sister. These Franciscan women who have taught, inspired and comforted hundreds of thousands over the decades are now intentional about passing on their mission and values to lay professionals who serve in the institutions the sisters founded.

This donated oak tree is one of the newer additions to the urban forest that the Sisters of St. Francis build on the Milwaukee, Wisconsin, property. (Courtesy of the Sisters of St. Francis)

Diana gave me a tour through the new convent facing Lake Michigan, with its administration offices, 48 apartments for assisted living and a 24-hour nursing unit for 32 sisters. In the lobby, I saw a parade of sisters pushing elderly ones in wheelchairs to the dining room; other sisters were chatting with one another.

On the second floor, Diana led me to a lovely all-weather porch with tables and chairs overlooking the grounds with maple, horse chestnut and spruce trees and, in the distance, the wooded hills.

"When the buildings are all down, the sisters will be able see the trees," Diana said. I think she was delighted that her sisters would enjoy the beauty of the land from a new perspective.

A decade ago, the sisters realized their 22 acres near Lake Michigan provided a wonderful opportunity to share the tranquil beauty of nature, to add to the diversity of urban wildlife and bird habitat and provide education to the surrounding community. They have planted their open green space with native grasses, trees and understory, restored the Dry Creek wetlands and, in the valley, established a large vegetable garden and beehives. Their attention to the natural world is truly Franciscan.

As I left, I thought: "What remains is their love for one another, a witness to us."

[Jean Molesky-Poz, Ph.D., is faculty in the Graduate Program in Pastoral Ministries at Santa Clara University and has taught for over 20 years at the University of California at Berkeley and at Santa Clara University.]