St. Francis of Assisi attained the heights of contemplation through his penetrating vision of creation. The idea of transcending the world to contemplate true reality would have been foreign to his thinking. Rather, he regarded earthly life as possessing ideal, positive potential as God's creation. Image: detail of tempera and gold on parchment "Manuscript Leaf with Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis of Assisi," circa 1320-42, made in Bologna, Italy, for Hungarian use (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin L. Weisl Jr., 1994)

This column has been updated at 4:30 p.m. Central time Dec. 1 to add a footnote.

Pope Francis issued his third encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, on the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, indicating his deep spiritual affinity with the founder of the Franciscan movement. The encyclical deepens the pope's vision of integral ecology laid out in his 2015 work, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" now extended to the social order on the level of fraternity and social friendship.

The pope's writings are comprehensive in his depth of analysis of ecological, social and technocratic structures that have created systems of separation, manipulation and disregard for the poor. He begins Fratelli Tutti by taking his cue from the "Admonitions" of Francis of Assisi, who writes in his 25th admonition: "Blessed is the servant who would love and respect his brother as much when he is far from him as he would when he is with him; and who would not say anything behind his back which in charity he could not say to his face."

Like Francis of Assisi, Pope Francis builds his new vision of social order based on the core virtue of fraternal love. It is clear that he is making every effort to enfold the Gospel life into the interstitial tissues of social order and, prima facie, his efforts to do so are admirable, if not outstanding.

The reliance of the pope on the Franciscan charism, however, is both endearing and troublesome. His select use of Francis of Assisi's writings to support his own agenda of reform deflects the trajectory of attention, away from theological reform within the church to social and global reform outside the church. Contextualizing the Franciscan charism in its historical context may elucidate some of the underlying tensions that persist in Pope Francis' writings.

The charism of Francis of Assisi lies in its pneumatic dimension. St. Francis was a man filled with the Spirit of God, to the extent that he rarely mentioned the name of Jesus in his writings. He was, in common parlance, a charismatic person. His conversion as a young man and renunciation of his father's inheritance led him to take up a poor, itinerant life, initially as a contemplative, and later as one engaged in the ministry of caring for people with leprosy. However, his single-hearted focus on the love of God and his dramatic efforts to live the Gospel life did not render him a good administrator of a rapidly growing movement, which grew fast and furiously.

Advertisement

Just a few years after he received papal approval for his way of life, there were several thousand followers. The new movement was chaotic and conflicted, as the brothers began to argue over questions of leadership, the need for formal study of theology and a need for structure. It is clear from the many hagiographies that Francis felt insecure and inadequate in the task of leading the movement. He spent more time traveling to secluded places with one or two brothers in order to pray than organizing the fraternities along the lines of love; however, he was clearly aware of the problems within the movement and the admonitions were composed as a set of guidelines to maintain charitable order.

Franciscan historians have shown that development of the Franciscan movement into an order was conflicted and divisive, to the extent that eventually the order split into two separate orders (Observant and Conventual), each claiming to be the direct descendent of the saint and most faithful to his charism. In other words, Francis of Assisi's writings on fraternal love did not play out in the formation of a just society of brothers and sisters. On the contrary, his writings were spiritualized and essentially marginalized, as the movement split into factions, the orders themselves becoming enfolded into the patriarchal and clerical structures of the church.

The genius of Francis was not in establishing a new religious movement of fraternity (although this is not to be denied) but the way he ushered in a new theological emphasis on materiality, without intending to do so. Since he had received little formal education in his youth, he never absorbed the Christian Neoplatonic attitude toward creation. Neoplatonists believed that the created world should motivate one to turn inward in the search for God. In order to know true reality, one had to transcend this earthly world and contemplate the spiritual world above.

Neoplatonism was marked by climbing the metaphysical ladder to the spiritual and divine realms by means of universal concepts. Conversely, Francis attained the heights of contemplation through his penetrating vision of creation. The idea of transcending the world to contemplate true reality would have been foreign to his thinking. Rather, he regarded earthly life as possessing ideal, positive potential as God's creation. Some regard him as "the first materialist" in the best sense of the word because of the way he looked on the material world — not for what it is but for how it is — God's creation.

Francis' nature mysticism included a consciousness of God, with the appropriate religious attitudes of awe and gratitude. He realized that matter is not an evil in opposition to a good God but rather it is the very image of God and the means by which we encounter God. God has entered into the material world, with all its fragile limitations, in and through the person of Jesus Christ. Image: Wool and silk tapestry "Christ Is Born as Man's Redeemer (Episode from the Story of the Redemption of Man), circa 1500-20, south Netherlandish (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Gwynne M. Andrews, by exchange, 1938)

Francis' nature mysticism included a consciousness of God, with the appropriate religious attitudes of awe and gratitude. He realized that matter is not an evil in opposition to a good God but rather it is the very image of God and the means by which we encounter God. God has entered into the material world, with all its fragile limitations, in and through the person of Jesus Christ.

Francis' realization of this tremendous mystery changed the way he viewed the world, not as a world of limited matter to be transcended towards a higher spiritual realm, but as matter filled with the Spirit of God, a world charged with divine grandeur. It is this material-theological vision of Francis that left an indelible mark on the theologians of the order, giving rise to the Franciscan school, initiated by Alexander of Hales and John of La Rochelle.

Alexander of Hales was a trained theologian who entered the Franciscan order at the age of 50 years old. His influence on the young Franciscan, Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, was significant. The Franciscans, like the Dominicans, established themselves at the University of Paris, which was a leading theological center in the 13th century. Although Bonaventure was trained in scholastic theology and influenced by Augustine, the Cistercians and Victorines, his most significant influence was Francis of Assisi.

St. Bonaventure statue at the National Shrine of St. Anthony and Friary in Cincinnati, Ohio (Wikimedia Commons/Nheyob)

While at Paris, Bonaventure was a colleague of Thomas Aquinas; however, he was elected to the position of minister general of the order due to political factions among the brothers. As a result, he had to leave university life and take up the role of administration. This role impelled him to think deeply about what constituted the Franciscan charism and the way Francis' own theological emphasis on personhood and materiality set him apart from the norms of scholastic theology.

Bonaventure brought together Francis' nature mysticism and Christ mysticism into his own theological synthesis, which he laid out in his final lectures at the University of Paris in 1257, a set of lectures he never completed, due to his untimely death. The first lecture is the "blueprint" of Bonaventure's theological vision. In this lecture, he brings together philosophy and theology in a new metaphysics of Christ at the center, which the late Franciscan theologian, Zachary Hayes, interpreted as a metaphysics of love.

Two generations after Bonaventure's death, John Duns Scotus, an English-trained theologian, began developing his own novel theology based on the charism of Francis of Assisi and the Oxford school of thought. Like Bonaventure, Scotus saw that Francis' materialist theology evoked a new metaphysics, and he set about developing the details of this new metaphysics based on philosophical principles of univocity and individuation. The turn from the Neoplatonic analogy of being, prominent in the theology of Aquinas, to univocity was a significant philosophical turn that the church had already rejected at the Fourth Lateran Council. More so, Duns Scotus advocated the primacy of Christ, stating that sin was not the reason for the incarnation; rather, the primary reason was the love of God.

Duns Scotus' primacy of Christ doctrine was radical and creative, although it was never officially embraced by the church. The rise of Franciscan scholar William of Ockham and the school of nominalism provided a philosophy that aided the rise of modern science, and the gap between Franciscan theology and the church widened. The church eventually turned its back on the Franciscan theologians and eventually mandated the theology of Aquinas as the official theology of the church in 1879 (Pope Leo XIII, Aeterni Patris).

Pope Francis has benevolently cherry-picked ideas from the writings of Francis of Assisi but essentially has left the official mandate of theology untouched. In 2000, the Franciscan Order of Friars Minor (OFM) initiated the Commission on the Franciscan Tradition, on whose board I served for six years. The purpose of the commission was to ensure the legacy of the Franciscan theological tradition and to bring the theological tradition into contemporary culture and life. The commission is still in existence but with little theological development; the emphasis is now on translations of texts and historical interpretations. In the early years of the commission, I remember sitting around the table with various Franciscans, all chiming in unison: If Franciscan theology had been accepted as the official theology of the church or even given an equal role (as Aquinas) in the formation of priests, the church would be in a very different place today.

It seems that our current pope wants to take the church to a new place in the world, not as an authoritarian leader, but as an animator of the spirit. He has a Franciscan vision, but he has ignored the novel theology ushered in by the early Franciscan theologians (although one can find aspects of Bonaventure's exemplarism in Laudato Si').

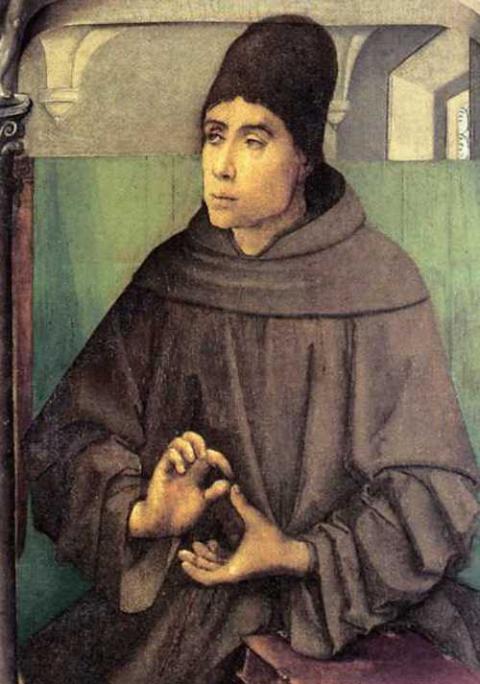

Painting "Scoto (Duns Scotus) - Studiolo di Federico da Montefeltro" by Giusto di Gand, Berruguete Pedro, circa 1472-76 (Wikimedia Commons/Galleria Nazionale delle Marche)

What the church will not reconsider is the place of original sin as the reason for the incarnation, despite the science of evolution. Duns Scotus thought that original sin distorted the meaning of God as love, essentially making the incarnation "plan B" for a fallen creation. He did not deny original sin but at the same, he said, it is not the principal reason for the incarnation. Rather, God is love, and from all eternity God willed to love a creature to grace and glory, whether or not sin ever existed: Christ is first in God's intention to love and to create. According to Hayes, Bonaventure, too, realized that the incarnation is not about the remedy for sin but the excess love and mercy of God.

Almost a hundred years ago, another Jesuit by the name of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, saw that Christianity was a religion compatible with the world of modern science, precisely because it placed a positive emphasis on materiality as the place of God's incarnation. One of the main problems Teilhard saw was the church's inability to reconcile original sin and evolution. The church posits an ambivalent if not dualist position, described by Pope Pius XII in his encyclical, Humani Generis (Paragraphs 36, 37): The material body may come about through evolution, but the soul is created immediately by God. Further, the church adheres strictly to the doctrine of monogenism (Adam and Eve as the source of original sin) and disavows any type of polygenism. (See footnote.)

As a scientist, Teilhard felt that the notion of original sin and its corresponding monogenism is incompatible with evolution. When he discovered the Scotistic doctrine of the primacy of Christ, he announced "there is the theology of the future!" Love and not sin is the reason for the incarnation; in Teilhard's view, love is the core energy of the universe. He devoted his life's work to bridging faith and evolution, realizing that matter and spirit are two dimensions of the same reality, and that evolution proceeds toward more complex relationships and greater consciousness. Teilhard was an advocate of what philosophers call today, the "new materialisms."

The cultural turns of the late 20th century are not only products of the technocratic paradigms and capitalism; they are new paradigms emerging from scientific insights on the plasticity of matter. Artificial intelligence rose in the mid-20th century because we learned how systems work along the lines of information and cybernetics. These discoveries undergird the rise of the cyborg, the hybridity of personhood, and the emergence of the posthuman in our own time.

Some radical transhumanists proclaim that technology will fulfill what religion promises because religion has failed to adequately address the ability of matter to change, in a way consonant with insights from modern science, including information, cybernetics and complexity. To put this another way, the doctrine of original sin thwarts the ability of the material universe, including the structures of human relationships, to realize the incarnational potential within. As a result, Christianity is impotent to effect real change in the world.

At left, the saint appears through a window to revive a dead woman so that she may make her last confession and, at right, he is leading a debtor out of prison in this detail of tempera and gold on parchment "Manuscript Leaf with Scenes from the Life of Saint Francis of Assisi," circa 1320-42, made in Bologna, Italy, for Hungarian use (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edwin L. Weisl Jr., 1994)

It is precisely because Pope Francis does not address the need to lift the official mandate of Thomistic theology or allow for new theologies, such as Duns Scotus' theology or Teilhard's theology, to influence church thinking or priestly formation, I am left wondering, who is he writing for? Without a theology that adequately deals with materialism, nothing can change. The church will not budge from its Thomistic-Aristotelian synthesis because the theological edifice is like dominoes. Once the Thomistic mandate is lifted, the chips will fall. What holds the church together in its universality is original sin (and hence Christ as true savior), the fallenness of matter, not the potential of matter to become something new.

It is good that Francis looks to St. Francis of Assisi, who was a man of keen wisdom and insight. Many brothers saw the poor man of Assisi as simple and ignorant, but he was deeply aware of just how fragile the human person is, as he wrote to St. Clare, "Do not look at the life outside, for that of the Spirit is better." Before the church looks at the world and its disorder, it might be worth assessing its own inner dysfunction; for an institution divided within lacks a Spirit of truth and cannot heal its own wounds.

Despite the dissonance between the pope's global outlook and the church's medieval paralysis, God continues to do new things, and a new theological vision of evolution forming on the horizon of the future is entirely within our reach.

Author's note: Polygenism was used between the 18th and early 20th centuries by scientists and church folk alike to support the view that multiple human strains or races were created, and that therefore white or Anglo or European peoples could not be genetically related to Black and brown or Indigenous folk.

Two sources are:

- Moritz, Joshua. "Darwin's Sacred Cause: The Unity of Humanity." Theology and Science, 13.1 (2015): 1-3.

- Slattery, John. "Evolution and Racism: Complementary Conclusions in Science and Catholicism." Commonweal (Feb. 4, 2020).

[Ilia Delio, a member of the Franciscan Sisters of Washington, D.C., is the Josephine C. Connelly Endowed Chair in Theology at Villanova University. She is the author of 22 books, including Making All Things New: Catholicity, Cosmology and Consciousness (Orbis Books 2015), and the general editor of the series Catholicity in an Evolving Universe.]