(Unsplash/Alexander Grey)

If Roman Catholic sisters' stories were generally well told, then writing their biographies wouldn't be nearly as interesting. However, most sisters' lives are recorded with too little detail, presenting an intriguing puzzle. These are some challenges I've encountered, along with ways I or others have addressed them.

The first challenge is modesty. By their very nature, most people in religious life, and particularly sisters, don't tend to talk or write much about themselves. Oh sure, we all know of the occasional sparkler who is all over social media and seems quite public and wordy, but those are exceptions. Most resist the solo spotlight, deflecting attention away from the individual and toward the group.

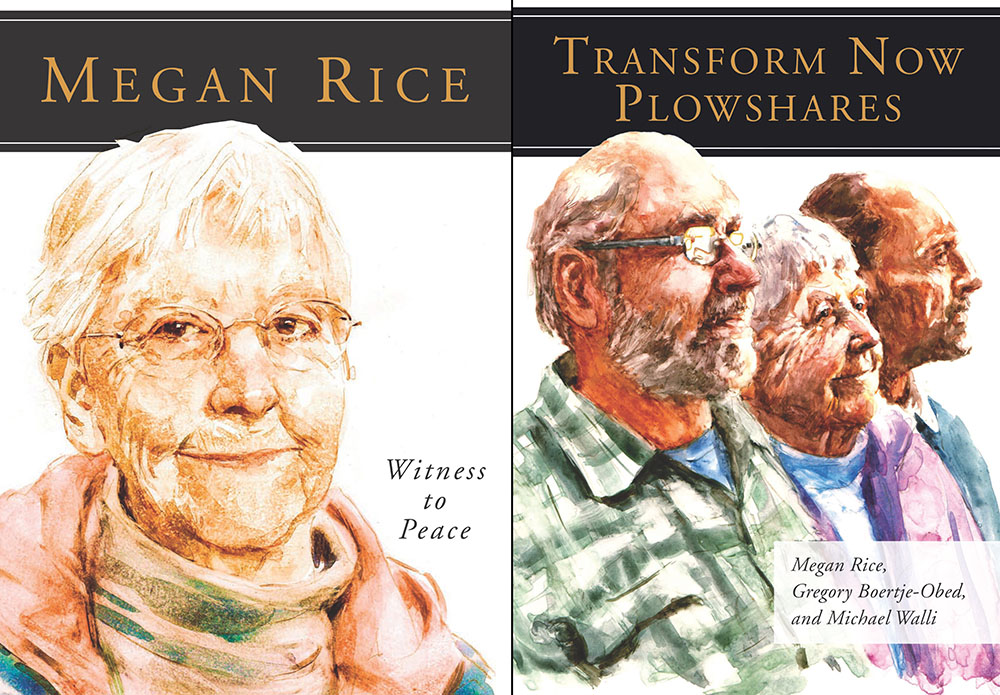

A case in point for individual vs. group was my friend Sr. Megan Rice of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus. She became famous for entering the kill zone of a nuclear facility to pray, along with two Catholic Worker men. After she and I learned that Liturgical Press had launched a book about her, the author stepped back and graciously nominated us to take it over. Megan insisted it be about the broader Plowshares movement, not just her. At her request, Liturgical Press changed the cover to include all three activists. That tripled my research workload, but Rice was relieved, and I believe it was the right call.

The original cover of the book is on the left. On the right is how Holy Child Jesus Sr. Megan Rice wanted it. (Courtesy of Liturgical Press)

Framing is a second challenge, because traditional biographical books starting with childhood sometimes don't sell well enough on their own. When St. Joseph Sr. Christine Schenk and I thought together on her book about Poor Handmaid of Jesus Christ Sr. Kate Kuenstler, Schenk had received feedback from an editor about the pitfalls of straight biography. She reframed the story, in her words, "to focus on Kuenstler's winning cases in Vatican court, which dramatically changed the trajectory of canon law to one that protects parishioner — and parish — rights." A canon lawyer, Kuenstler had represented those whose vibrant parishes had been closed against their will, often to pay church debts.

"What was it about Kate that kept her hanging in there for 10 years?" Schenk told me. "What spiritual grounding kept her going even though she had a really terrible three years, a dark night of the soul? What I wanted to get at was the stuff that nobody sees, what was happening in her soul that enabled her to keep going, even though at first she kept losing every case. Sort of like what kept Teresa Kane going when the Vatican was trying to get rid of her?"

Digging into motivations rather than origins is something I learned from Schenk as she reframed the story. Bending Toward Justice: Sr. Kate Kuenstler and the Struggle for Parish Rights was the result, and Sheed & Ward published it in 2024.

Misrepresentation and even caricature presents another challenge, and the example that comes to mind is Dominican Sr. Ardeth Platte, who with fellow Dominican Srs. Carol Gilbert and Jackie Hudson carried out numerous antinuclear actions often resulting in jail and prison time. Although author Piper Kerman, who knew Platte personally in Danbury prison, described her fairly accurately in the book Orange Is the New Black, the character of "Sister Ingalls" in the Netflix series deviated wildly, imagining her as a self-promoter and even something of a grandstander.

My interview with actor Beth Fowler revealed a thoughtful performer who befriended Platte and Gilbert and understood their motivations. She had even discerned to be a Dominican sister of Caldwell in her youth. But the writers for the character seemed to go their own way.

Dominican Sr. Ardeth Platte (CNS/Catholic Review/Owen Sweeney III)

I am currently writing a biography of Platte, and part of my job will be to encourage people, as she always did, to read the book for actual history, and watch the show only for fun, and to see Fowler's wonderful work.

Wikipedia is another area where writing about sisters' lives can become fraught, and I wrote previously for GSR about why notable Catholic sisters need Wikipedia pages. As the largest reference work in history, Wikipedia has the widest readership ever known. Yet according to its own statistics, only 10-15% of its editors are women. Determined editors, often male, seem to take a special interest in tagging sisters' biographies as insufficiently notable, and thus candidates for deletion.

For example, I published a Wikipedia biography of Benedictine Sr. Arleen McCarty Hynes, and almost immediately another editor nominated it for "speedy deletion," because he thought she wasn't prominent enough. Instead of arguing, I tagged editors associated with an award-winning feminist WikiProject called Women in Red. They opened one of Wikipedia's structured debates, with moderation, and a quick verdict went in my favor. You can read the whole story in the magazine Benedictine Sisters and Friends.

Congregations with notable sisters who lack Wikipedia pages may contact me, and I'll either create the page for you or show you how to do it.

Advertisement

Some of the sisters I profile on Wikipedia are from the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Congregation archives are filled with mini-biographies praising deceased sisters in glowing terms as being the most holy, most virtuous, etc., especially before 1900. We don't learn about rivalries, infighting, weaknesses of faith, or really much of anything that makes a person, well, human.

A tradition of sanitizing difficult facts often backfires for posterity, however, because hiding sisters' flaws can also make them seem dull. The most famous example is probably St. Teresa of Calcutta, whose story was initially told in too-perfect terms. She became more deeply relevant to many of us when we learned of her now-famous crises of faith. Millions responded not with scorn, but relieved cries of "I can relate!"

We should ask who it truly serves if we hold back biographical information about members of any religious congregation. Why snuff out their witness by reducing them to simple dates of birth, entrance into religious life, and death, such as we see in most of their cemeteries? We know from long precedent, including the Vatican's own tradition of consulting what used to be called the "devil's advocate," that all true saints are tested. Sisters' lives will seem even more worthy of emulation if we understand them more fully, including the very real temptations and struggles they have had to overcome.