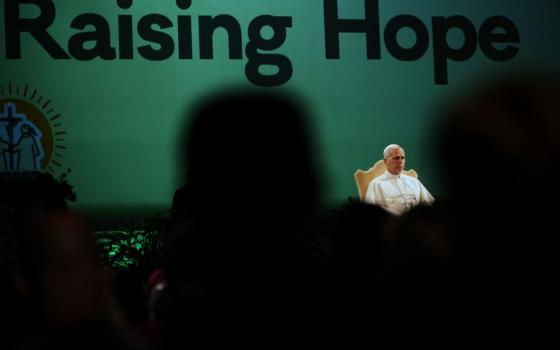

Copies of Pope Francis' encyclical on the environment, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," are stacked on a table prior to a presentation on the encyclical June 30, 2015, at U.N. headquarters in New York City. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

Ten years after the release of "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" — a document lauded for its promotion of integral ecology and the recognition that everything created by God is imbued with value and worth — the basic goal of engaging women in the development of official Catholic social teaching remains elusive. Despite Pope Francis rightly stating, "We need a conversation which includes everyone, since the environmental challenge we are undergoing, and its human roots, concern and affect us all," Laudato Si' and its follow-up teaching Laudate Deum failed to do just that when it comes to women.

By disregarding current scientific approaches to the intersection of gender and ecology, neglecting to cite female scholars and omitting references to the work of women religious, Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum perpetuate "the women problem," which is to say they omit them.

To acknowledge patriarchy within the church is nothing new. The failure to centralize, regard and learn from women and their experiences abounds in Catholic theology and ecclesial realities. To his credit, the late pontiff in important ways acknowledged in Laudato Si' that there are disproportionate burdens placed upon women and children in cases of fresh water scarcity and pollution, in particular.

Pope Francis listens during an ecumenical prayer vigil before the assembly of the Synod of Bishops in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican Sept. 30, 2023. (CNS/Vatican Media)

But still, in both Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum, gender is only briefly noted as a factor that influences people's experiences and the disproportionate social-ecological burdens placed on their lives. The realities of women are not generally engaged in ways consonant with how the natural or social sciences tend to treat gender and climate impacts.

Throughout much of Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum, Francis is clear on the value of the contemporary sciences and social sciences. But the best of those disciplines is not brought to bear on discussions of the gendered impacts of climate change. The unevenness is epistemically problematic and has a flattening effect on how the burdens associated with climate change are analyzed and understood.

In addition to this methodological flaw are omissions of citation. There are no women cited in the footnotes of Laudato Si'. This is silly. There are brilliant women — who are Catholic, not Catholic, on Pontifical Academies, and elsewhere — whose scholarly work deserves engagement.

Yes, women contributed to some of the reports cited in Laudato Si' and Laudate Deum. But what of the women scholars who are experts in their own right, such as Celia Deane-Drummond or Ilia Delio or Ivone Gebara, whose significant work on the topic of ecotheology remains unmentioned (and that’s just in the English-speaking world).

Advertisement

Now, granted, in Laudate Deum, Donna Haraway — a brilliant scholar who says that she was formed by a Catholic sacramental consciousness but whose conviction "that it was morally insupportable and wrong to remain within the church preceded loss of belief" — shows up in a strange citation about multispecies relationships that refers to a chapter where she discusses agility training her dog. The citation choice is neither elaborated on nor explained. Haraway herself presumes that "some baby Jesuit" read her work in graduate school and got it into a footnote.

And yet, even more galling than the failure to cite women academics in the footnotes is the failure to mention — in the footnotes or anywhere else — the communities of women religious that have been incarnating, and in many ways anticipated by decades, Francis' ideas on care for our common home and the climate crisis. Many of these communities have long understood and implemented the charisms of care for creation and environmental justice, as Sarah McFarland Taylor pointed out back in 2007 in her book Green Sisters: A Spiritual Ecology.

For many women religious, care for creation is integrated with attention to problems of poverty, economy, education and gender inequity. These demonstrable commitments range from the quotidian to the structural: for example, promoting the idea of fresh water as a human right; divesting from companies that privatize fresh water or exploit natural resources; summoning religious liberty as a defense against eminent domain attempts by fossil fuel companies; working toward land restoration and, in some cases, reparative land justice.

These examples are from religious orders in the U.S.; worldwide, there is even more that women religious are bringing to life, yet none of their vital and prophetic work on ecological education, ecological conversion, or economic and ecological justice is mentioned in Laudato Si' or Laudate Deum. Nor (to the best of my knowledge) was it brought up in prominent expository moments, such as the formal Vatican launch of Laudato Si'.

My hope for the Catholic Church in the next decade is for it to correct this gap in papal teaching — specifically by adopting an epistemic preference for, and foregrounding of, those who are already doing academically rigorous, ethically reliable and ecologically prophetic work on gender-attuned ecological theology and environmental justice.