A health care worker receives a dose of Sinopharm's COVID-19 vaccine Feb. 9 in Lima, Peru. Peru's bishops denounced the giving of vaccines to VIPs instead of essential workers soon after the vaccine became available. One of those who received the vaccine was the papal nuncio. (CNS/Reuters/Sebastian Castaneda)

Eighteen months in, the coronavirus pandemic has ravaged Latin America: The region accounts for a third of the world's COVID-19-related deaths despite accounting for 8% of the population.

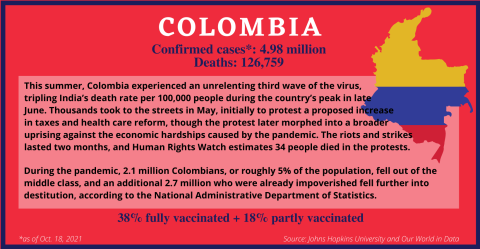

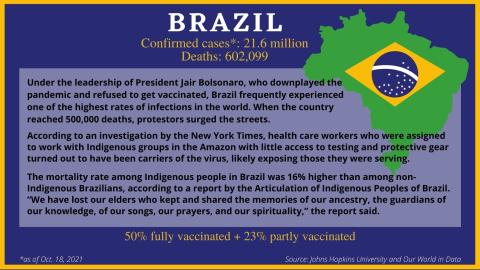

Relative to its population, Peru has the highest number of deaths in the world per capita. Over the summer, Paraguay claimed the world's highest daily death rate, with 19 times as many deaths as the United States per capita. Colombia and Argentina together have tallied more deaths than all African nations combined. Brazil, which in June set the record for the highest number of new cases in a single day, recently surpassed 600,000 COVID-related deaths.

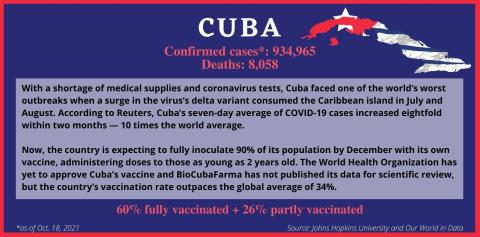

Following promising vaccine developments, the situation on the continent is improving. The Pan American Health Organization, or PAHO, which thus far has delivered more than 50 million doses throughout the hemisphere, is working with centers in Argentina and Brazil to develop new vaccines comparable to Pfizer's and Moderna's and recently purchased more than 8 million vaccines from the Chinese manufacturer Sinovac.

The historic social and political factors that exacerbated the catastrophe in the first place remain intact, however, leaving little room for optimism among some that the southwestern hemisphere is in a position to emerge from this adversity stronger than before.

Yoselin Marticorena, 26, talks on her cellphone March 3 while sitting outside a tent on the grounds of Hospital Villa El Salvador in Lima, Peru. She was living in the tent while waiting for information regarding the health of her father, who was hospitalized with COVID-19. (CNS/Reuters/Angela Ponce)

Those who spoke with Global Sisters Report shared recurring themes that united the Caribbean, Central America, and the Andes when assessing the long-term socioeconomic causes and effects of the dire coronavirus situation in the region, including political corruption trending toward authoritarianism, deep-seated poverty with a strain of government dependency, and a deteriorating middle class.

And that is in addition to the struggles the countries already faced pre-pandemic, including a Venezuelan refugee crisis, a surge of street protests, dilapidated health care systems, and intergenerational households that would eventually put elders at high risk of exposure to COVID-19.

"What we have here is no less than a third of the Latin American population living in poverty with underdeveloped human capacities, discarded in the current economic system," said Agustín Salvia, a sociologist and social ethicist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina in Buenos Aires, where he directs the university's Social Inequalities Observatory.

"The problem is structural. The economic systems of Latin America are not in a position to guarantee work, employment, social security or welfare systems for the population."

Gustavo Delgado, 52, who lost his job because of the COVID-19 pandemic, drinks a mate Dec. 15, 2020, at his home in Buenos Aires, Argentina. (CNS/Reuters/Agustin Marcarian)

The social, educational, health and economic progress Latin America experienced between the 1980s and 2000s yielded a robust middle class, he noted — with some exceptions, including Salvia's Argentina. But he says the pandemic revealed just how precarious the middle class had been all along.

The insecurity of the middle class, resulting in recent social upheavals throughout the continent, "did not happen because of the coronavirus," he said. "But the coronavirus made it worse."

According to an Oct. 14 report by PAHO and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, the health crisis sparked the sharpest economic decline of the past 120 years in Latin America and the Caribbean, where economic performance was the worst of all the developing regions. Combined with the near-zero economic growth in the five years before the pandemic, the continent experienced a record rise in unemployment, poverty, extreme poverty and inequality.

"The State has played a crucial role in responding to the challenges of the pandemic; and it must continue to do so in forging a new direction for public policy, to build more egalitarian, inclusive and resilient societies," the report stated.

Demonstrators protest to demand better wages, COVID-19 vaccines and resources for soup kitchens June 18 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. (CNS/Reuters/Agustin Marcarian)

Sisters help where they can

In the outskirts of Lima, Peru, where Maryknoll Sr. Anna Manauis has been ministering for decades, nearly three-quarters of the workforce is informal. Individuals create their own daily wages as street peddlers, farmers who sell produce in local markets, or construction workers, for example. For them, pandemic-related lockdowns mean no work or wages.

Indeed, half of Latin America and the Caribbean's labor force is in the informal economy, unable to make the transition to working from home.

"They don't even have any means to buy food, to put food on the table, much less being able to buy materials for the homeschooling for the kids, like tablets," said Manauis, co-coordinator of the commission of human rights for the Conferencia de Religiosos y Religiosas de Peru. "A lot of the kids are not getting into classes."

Protesters and street vendors argue with riot police over new government restrictions Feb. 1 in Lima, Peru. (CNS/Reuters/Sebastian Castaneda)

In a May 31 report, the Peruvian government stated that an accurate death toll from COVID-19 was nearly three times higher than its original estimates — more than 180,000 instead of an estimated 68,000 — after reclassifying fatalities and combining databases. Since 9% of its coronavirus cases result in death, Peru claims the world's highest death toll relative to its population.

Manauis also noted the "political fiasco" the country was experiencing before the pandemic that has continued, which in turn intensified the politics: In the last five years, Peru has had five presidents — including three in one week — whose terms in office ended with an impeachment, resignation, a suicide, and jail time for three as they were investigated for bribery.

Comboni Missionary Sr. Socorro Palomino said her congregation's goal as they minister to Peruvians is to mitigate the "paternalism" and "dependency" on the government they often witness among the country's impoverished.

During the pandemic, the congregation empowered local women to organize a soup kitchen in the outskirts of Lima, for example, allowing the women to buy large quantities of food wholesale to sell to their community at affordable prices, all while making just enough to support their families.

"This effort is all about mutual help," said Palomino, who is involved in women's issues with the human rights commission of Peru's religious conference.

Though she expressed distress at what she said is a deteriorating work ethic and abysmal quality of education for the middle class as well as for those living in poverty, she said this past year has confirmed for her that "the Peruvian people are fighters, and solidarity is growing."

Women distribute food in Cajamarquilla outside Lima, Peru, buying large quantities at affordable prices to sell cheaply to the community while making a small profit for themselves, said Comboni Missionary Sr. Socorro Palomino, who helped organize the women in this effort throughout the pandemic. (Courtesy of Socorro Palomino)

Sr. Margarita Mangual Colón, a Dominican Sister of Fátima in Guánica, Puerto Rico, echoed Palomino's concern regarding a lack of work ethic and government dependency. She said the stimulus money the U.S. government provided last summer discouraged Puerto Ricans from taking on vacant jobs on the island, such as those in supermarkets or fast-food restaurants, on plantations harvesting coffee beans and fruit, or in construction.

But that concern doesn't stop the Dominican Sisters of Fátima from collecting and distributing donations for struggling locals — including food, masks, and disinfectants — as well as organizing free educational talks on Facebook Live with social workers, sisters and psychologists to offer practical guidance and accompaniment for those struggling with quarantines or their health.

"Many people feel lost, alone, depressed, anxious, so the volume of work for psychological assistance in particular has increased a lot," Colón said.

In addition to the pandemic, Puerto Ricans had to stay vigilant through two hurricane seasons, and they are paranoid about the ongoing tremors after the January 2020 earthquake that struck the southwest months before the start of the pandemic.

"It just felt like one thing after another," Colón said.

For many governments, 'there is no exit plan'

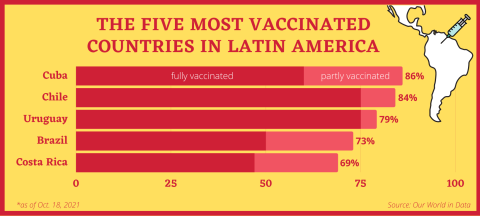

Fortunately, the vaccination effort in Puerto Rico avoided the political partisanship that took over media coverage of the pandemic elsewhere in the United States. Nearing an 80% vaccination rate for those with at least one dose, the U.S. territory takes the lead when compared to the United States' 65% rate, as of Oct. 20.

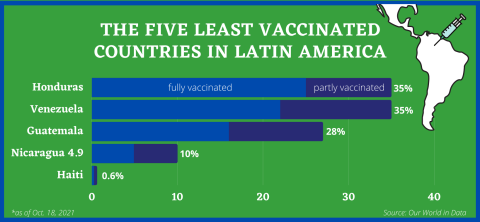

Guatemala, meanwhile, has one of the lowest vaccination rates in Latin America: About 25% of its eligible population is fully vaccinated.

María Eugenia Estévez Romero de García, a physician in Guatemala City, said the hospitals in Guatemala and Honduras are overwhelmed.

"There is no decent salary for first-rate doctors," leaving the health care systems in want of qualified personnel, she said. "Bad hospitals. Bad health centers. Bad doctors due to the fact that they're not paid what they deserve."

"This pandemic laid bare what our Ministry of Public Health really is and what we have not wanted to see," she said. "We are totally helpless."

Advertisement

And because multigenerational households are the norm in Guatemala and elsewhere in Latin America — Colón in Puerto Rico also highlighted this trend — the casual attitudes toward the virus among young people, who are less likely to become seriously ill from the coronavirus, endangered the grandparents with whom they live, Estévez said.

Although Guatemala received mass shipments of vaccines from the United States and other countries, there are not enough vaccines available to the general public, which points to political corruption, she added.

Indeed, scandals of preferential treatment for the first vaccines gutted trust in democratic institutions throughout several countries in South America — including Brazil, Argentina, Peru and Ecuador — where politicians and their loved ones were given special access to the then-scarce supply.

Medical workers take care of patients in the emergency room of the Nossa Senhora da Conceicao hospital March 11 in Porto Alegre, Brazil. (CNS/Reuters/Diego Vara)

Salvia, who coordinated the Latin American Episcopal Council's (or CELAM) study on the pandemic, "The social landscape during COVID-19 in Latin America," shared his concerns that the coronavirus has greatly contributed to the "authoritarian climate" growing in the region.

An elected official's legitimacy is not established solely through elections, he said, but also through symbolic leadership; therefore, in times of crisis, the authoritarian muscle is flexed to maintain the illusion of power that those in charge worry is slipping away.

"That is clearly expressed in Nicaragua, Venezuela, Cuba (although that's not a democratic system) ... Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, to name a few," he told GSR. "We can talk about Argentina, though it's less extreme there, and Chile and Bolivia have not had authoritarian expressions yet, but their power is there."

"As long as the new governments fail to earn income, be generous, or fail to achieve an integrative consensus, the response of the political system is one of the greatest authoritarianisms," he said.

Salvia said what worries him most when considering the future of Latin America is that "it is not politically possible to build a government coalition with a clear strategy for handling the crisis — and not only the COVID crisis, but the structural crisis" regarding the lack of economic mobility.

The authoritarianism that arises in times of sickness and death, he said, "indicates that the government was interested not in building consensus, but in controlling the actors."

"There is no exit plan; the government does not have a plan beyond the day-to-day or beyond the next elections."

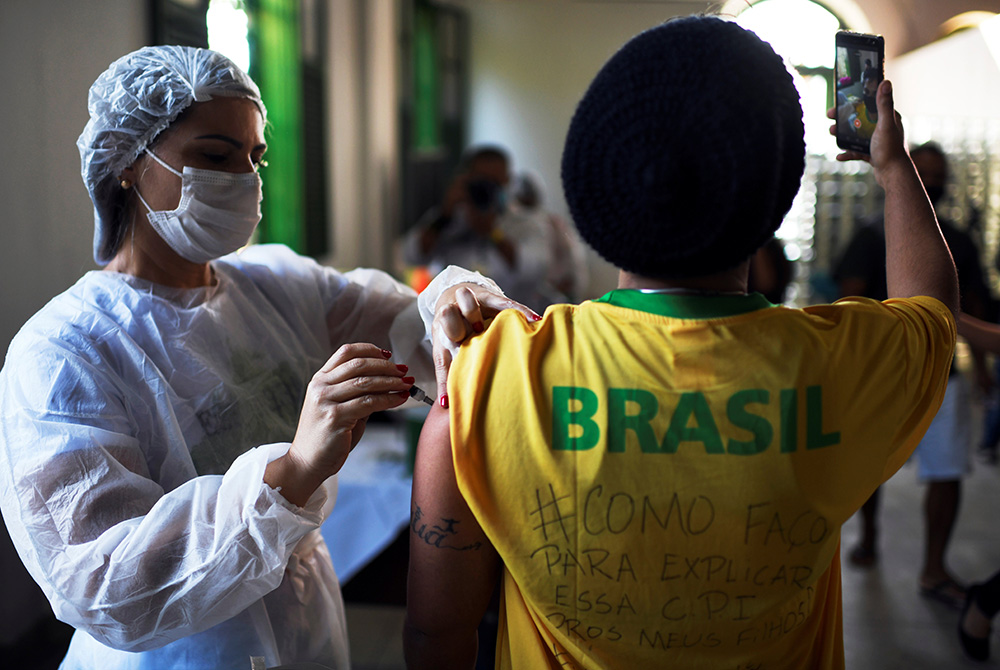

A health care worker administers a dose of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine to a resident taking a selfie in Rio de Janeiro on July 10. (CNS/Reuters/Lucas Landau)

Progress, but still so far to go

By September, the sudden drop in coronavirus cases throughout South America started to offer hope that the worst of the pandemic is finally behind the region that was once its epicenter.

Experts told The New York Times that the speed with which governments were able to vaccinate some of their populations is largely the reason behind the drop, as vaccination campaigns were largely without the inhibitions of "apathy, politicization and conspiracy theories" that left the United States vulnerable to the virus's delta variant.

Though the region is indeed witnessing a steady increase in vaccination, of its 49 countries, 25 have less than 40% of their populations fully vaccinated, according to the Pan American Health Organization.

"We have moved from an emergency in 2020 to a protracted health crisis in 2021," Alicia Bárcena, executive secretary of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, said in a press release following the Oct. 14 report.

"Last year we argued that without health there could be no economy and today we say again that without health there can be no sustainable economic recovery. The priority is still the need to control the health crisis, taking a comprehensive approach and speeding up the process of vaccinating the population.

"The importance of strengthening the region's capacity to produce vaccines and medicines and overcoming the external dependence faced during this pandemic has become clear."