Women discuss the issues at the Non-Governmental Organizations Forum held in Huairou, China, Sept. 3, 1995, as part of the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing. (U.N. Photo/Milton Grant)

It's Beijing + 25. It's 25 years since more than 40,000 women and I gathered in Beijing for the U.N.'s Fourth Conference on Women. It was one of the major experiences of my life. Women came from everywhere full of hope, determined to bring all women into the mainstream of public life. The one based on equality, on peace, on liberty, on respect.

Twenty-five years ago, those women and all the women they'd come to represent from around the world stood up and said, "No!" No to invisibility. No to exclusion. No to powerlessness ever again. And then they said yes — and listed all the things that needed to be done.

I reviewed all my notes from those days and even reread Beyond Beijing, the book I'd written about it when we returned. The overview brought life into focus: Here we are celebrating the year of the woman as well as a national election at the same time. And one thing is clear: There are things bigger than partisan politics to worry about. There is something more demanding than personal growth alone. There is something crucial to our personal lives and essential to the character of the nation at the same time: feminism and sexism.

Feminism and sexism are two different perspectives on life that are the foundation of everything that happens everywhere. In this election now, in every election yet to come, in every home and workplace, we must embrace feminism and eliminate sexism if we are ever to become the people we were born to be.

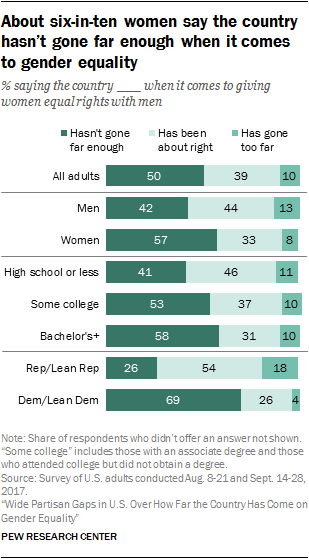

What's more, I also know, according to recent Pew Research Data, that at least 44% of the men of the country think sexism — and feminism — are over. They're tired of hearing about it. They consider it finished, ended, resolved. The way things are, the men told researchers, are "just about right."

Yet, a huge swath of women are torn between being grateful that things are not what they used to be for women, yes, and at the same time, certain that they have to get better and soon — or else.

Or to put it another way, think of this one:

Elizabeth Blackwell was refused entry into every medical school in the United States. No women allowed. Then, 150 male students at Geneva Medical School in New York, in a fluke, voted to admit her and the administration relented. In 1849, Blackwell became the first woman doctor in the United States, only to be rejected her entire life by the men in the field. So eventually, she gave up trying to be accepted there. Instead, she founded her own hospital for women students. Good event, bad event? Who knows?

I have begun to realize that over 200 years later, the feminism/sexism divide is still a good event/bad event issue: Something we know is good and critical to our future, yes, but, due to sexism, is still far from perfect. Something on which the very quality of our lives depends, as did the attempt to stop the emergence of women doctors.

The point here is that life is always far from perfect but, while accepting what is, we must realize that every situation is for its own time only. We must take what's in front of us and grow on.

Ask American women the truth of that. They are experts at the "good event/bad event" life.

American white women finally got the vote in 1922, our black sisters much later. A good event, finally. But women did not get full civil rights to serve on juries until the 1970s. Law, someone somewhere had decreed, was a male preserve. Nor did women have the right to own a credit card — to manage her own money independently — until 1974.

World War II, in a warped way, was a good event for women. Being dumped in the workforce — which only recently was all but totally closed to them — taught women independence, public presence, self-esteem. Until, of course, the men came home from the war to reclaim those jobs and reassert her dependence and their superiority.

Advertisement

The Equal Pay Act was a very good event, it seemed. The law passed in 1963 and stated that women were to be paid the same amount as men for doing the same work requiring the same skills. Instead of paying women the same wage they were paying men for doing the same thing, though, companies began to title the same jobs differently. They labeled jobs for men one thing and paid women less for the same job by calling it something else now.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 promised equal employment opportunities but for men-only initially. Then, under pressure, women were included as worthy of equality two years after it passed. The original law defined race, religion and disabilities as worthy of protection in the workforce. But not sex. (Which, of course, threatened to leave women unemployed, destitute and powerless to take care of themselves and their children. Bread, milk, food, transportation and rent cost the same for women as for men, but women, working side by side with men, could not be sure that they would be paid enough to afford them.) No wonder the trafficking of women and children began to soar.

The best event of all came with the admission of women and girls into higher education. Professional schools opened — reluctantly in many places — but the holy grail was finally there. Women, it promised, could also be lawyers and surgeons, judges and dentists — once all forbidden to them. But it also brought with it limited promotions and sexist manipulation of women's compensation.

And if you are sitting there basking in the notion that all of that has ended now, listen carefully: The United States of America has been ranked this year as one of the worst countries for women while it is the strongest military power and the richest economic power in the world. The United States score of 83.75 on gender equity has been flat for 10 years and is now tied with Malawi, Kenya and the Bahamas while more than 60 other countries scored higher than the U.S.

Why? Because of all the developed countries of the Western world, The United States offers less political, social and economic participation for women — fewer ways for a woman to grow and become a fully confident and self-reliant adult. Worse, violence against women is a disease in the United States. America, that is, threatens more likelihood of suffering personal and psychological violence for women than in other similarly developed countries.

In the United States, in other words, that bulwark of power and affluence, a woman cannot walk her dog alone at night without fear of assault.

Georgetown University's "Women, Peace and Security Index" ranks the United States of America 17th out of 28 developed countries of the Western world. That means, of course, that the degree of an American woman's participation in government, in economic development, and in freedom from violence lags behind many other countries in the developed world.

The Equal Pay Act and Civil Rights Act notwithstanding, women are still paid less than men for doing the very same work while corporations go their merry way — closed to women in general, dripping with sexism, and intent on ignoring the newly begun emergence of woman as an adult.

No wonder that, according to the Pew Research survey of American women under 30, 40% of them want to leave the United States.

In the United States, the #MeToo capital of the world, men do not really respect women; they harass them. And when women do get a job here, at the highest level of corporate enterprise, they too often find that the job depends not on their talent but on their sexualization. Ask the Weinsteins, the Ailes, the Epsteins and the media about that.

Yes, women could apply for high places in highly touted industries — entertainment, art, music, science, academia — but too many jobs came with the kinds of stipulations no man would ever face. "Work clothes" were mandated for women: short skirts, open shirts, high heels, and heavy makeup for women who really wanted the job. Not to mention sexual favors and sexual harassment. In fact, the first sexual harassment trial in the United States came in 1974 and is more common now than ever.

Good event, bad event — who knows? Is every unmasking of sexual abuse simply a portal to more feminism?

Are we seeing progress or are we refusing to see the normalization of second-classism, all the time talking about equality but demanding subordination of women's minds, bodies, ideas, values and souls? According to the Gender Norms Index by the U.N. Development Program, in a world that has never needed the implosion of patriarchy — the relinquishment of patriarchal norms and values, goals and social structures — more, almost 90% of people are biased against women.

As a result, Beijing and its assertion of human rights for American women is still a promise-in-waiting in a country that won't ratify the ERA — the Equal Rights Amendment for women.

The United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing on Sept. 15, 1995 (U.N. Photo/Yao Da Wei)

The Beijing Platform's commitment to the promotion of women in decision-making, in the economy, in health and welfare issues is unfinished in a country that still can't or won't provide day care for the children of working mothers.

Finally, the platform calls for the presence of women at the highest levels of authority. A country that boasts its educational system and its commitment to equality and progress that can't elect a woman president — despite the fact that 70 other countries have already done so and 29 more having sitting female executives at this time — is an abomination.

From where I stand, the question for people of faith must be, "Where are our churches on these subjects?" As a general rule, maintaining male structures, theology and liturgy are more important to them than public preaching and advocacy for the human rights and spiritual worth of the other half the human race. Instead, women everywhere are left invisible, powerless and absent from the center of our human institutions — in both church and state.

When the churches themselves stop teaching and modeling sexism, the justification of sexism by the God-talk that says, "God wants it this way," will end, those heresies will end, inequality will end, and together both men and women will flourish.

In the meantime, we will go on struggling from point to point, trying to prove the humanity of women one incident at a time and ignoring the Beijing Platform on which they stand.

Beijing Platform issues:

- Women and the environment

- Women in power and decision-making

- The girl child

- Women and the economy

- Women and poverty

- Violence against women

- Human rights of women

- Education and training of women

- Institutional mechanisms for the advancement of women

- Women and health

- Women and the media

- Women and armed conflict

[Joan Chittister is a Benedictine sister of Erie, Pennsylvania.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Joan Chittister's column, From Where I Stand, is posted to NCRonline.org. Go to this page to sign up.