St. Joseph Sr. Rosemary Flanigan speaks at the Center for Practical Bioethics' annual dinner in 2018. (Courtesy of the Center for Practical Bioethics)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

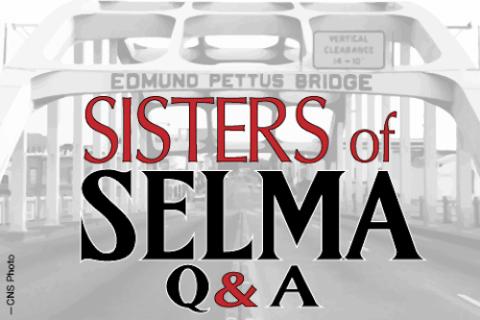

Editor's note: Every two weeks through the end of September, Global Sisters Report will feature interviews with Catholic sisters and former sisters who worked and/or marched in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. We wanted to give these sisters an opportunity to share their thoughts about current racial events, protests, and Black Lives Matter. These sisters and former sisters were all featured in the 2007 PBS film "Sisters of Selma: Bearing Witness for Change" by Jayasri Hart.

GSR invites any sister or former sister who marched or worked in Selma in 1965 to be part of this Q&A series. Email Carol Coburn at [email protected] if you would like to be interviewed.

Sr. Rosemary Flanigan has been called "ethics in action" and a "force of nature." Both monikers have been appropriate for more than 50 years.

As a young nun in the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, she flew with five other sisters from St. Louis, Missouri, to Selma, Alabama, in March 1965 to participate in a voting rights march.

Writing about her experience for America magazine in 1965, she talked about the powerful insights she gained. During her ride from the Selma airport, she was stunned by what she saw. To avoid danger, her car drove through "muddy back alleys past dwellings unlike any I have seen, even in St. Louis' worst slums."

Walking into Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma, "I looked up for the first time into the faces of one of the most diversified groups I had ever seen." Flanigan saw Black and white people of all ages, women and men, college students, children, Protestants, Catholics, rabbis and clergy from many Christian denominations.

The next afternoon, back in St. Louis, she and her travel companion, Sr. Roberta Schmidt, were invited to participate in a popular radio talk show to field questions about their experience. The two-hour event jammed the phone lines, with calls coming from 40 states and Canada. More than 10,000 calls were registered. Both high praise and anger filled the airwaves. Her eyes had been opened, and her world and her worldview changed forever.

Flanigan is a philosopher. She completed her doctorate in philosophy at St. Louis University and worked in academia for almost three decades, teaching philosophy and ethics to undergraduate students. From 1992 to 2010, she served as a director of ethics and educational development and as an ethics and program consultant for the Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City, Missouri.

GSR: How would you compare your 1965 Selma experience to what you're seeing around you in 2020? What's different?

Flanigan: It's a different world. When I think back on Selma in 1965, my emphasis was on slavery. Neither church nor society saw the evil that went on for so long. When we went down there, I was a typical white, middle-class, well-educated woman going into the deep South. I knew my family never had slaves, I knew my community never had slaves, I was removed from slavery.

St. Joseph Sr. Rosemary Flanigan, fourth from right, takes part in the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. (Courtesy of the Center for Practical Bioethics)

What I did not realize until years later was what that practice had done in terms of white supremacy. I had never heard the term of white supremacy until about 10 years ago. So, a few years ago, I took some time to understand what white supremacy meant in my lifetime. And that's what opened me.

Until then, I don't think I had a clue how deeply that racism is in the very marrow of our bones. I did a lot of praying over white supremacy, and that's when it became clearer to me. When going to Selma, I wasn't really aware of what I was engaged in. The world of 1965 and the world of 2020 are different worlds for me.

Are your expectations different in 2020?

Yes, my expectations are different. We stood with Black people in Selma, but what a little bitty thing we did. Yes, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 helped us do something. Although our expression was sincere, we didn't see the depth of what we were protesting. We didn't push it to conclusions that would make life better for Black people and the vulnerable people protesting.

We're sometimes big with words, but we don't see that it takes a lot more than words to make a change at all. That is different in 2020. This protest has had effects that others haven't. Worldwide, I think we're at a tipping point. It's not going to be simple. George Floyd was the tipping point.

I am concerned that the presence of violence in some protests will frighten whites who become blinded by fear and fail to see that the overwhelming protests are nonviolent and peaceful. We whites are much more interested in keeping law and order: nothing loud and noisy, please.

Some people look for something that covers up the lack of justice. So, the focus is on "law and order" above all, which allows historical amnesia for whites who have forgotten why this racial unrest is happening in the first place. Issues of equality and justice become forgotten.

What would you say to activists, particularly young people? How would you mentor them?

I would tell them how I grew, what I was like. I would tell them that they have the opportunity to mix with people of color in their schooling. You need to make opportunities to get to know others. You need to go and interact, not sit back and philosophize about it. You need to focus on common ground.

I'm a believer in nonviolence. We need to come together because we've lived our lives without needing to come together. When we do this, we miss out on tremendous gifts from those not like ourselves.

Talking about right relationships is the basis for justice. We have to establish a sense of common humanity. You can't have justice unless you have right relationships — with God and your fellow human beings.

What is the role of religious congregations in the fight for racial equality in 2020?

Sometimes, particularly during COVID, we are so content to stay in our nice apartments and let the world go by because we are protecting "our dear neighbor." Well, that is true, but we need very much to get groups together. After COVID, it would be good if we could be the firecrackers to bring groups together to talk.

I kept watching all those protests and kept looking for a Roman collar. We haven't had enough religious participation. It is important that religious groups say to people: "This is where we stand." For me, it was important that my community made a statement after the death of George Floyd.

Advertisement

Whatever it takes, we need to remember all the things that disturbed us in the past so we can know the pain of what's going on. We need to build up community, not put people in little boxes. That's not what Christianity is about, and that is not what good living and right relationships are about.

What else would you like to share?

I want to share some recent thoughts that have been important catalysts for me as I reflect about the world in 2020.

In a recent essay for National Catholic Reporter, Sr. Joan Chittister wrote: "The people we've kept down so they couldn't rise up, we condemn because they don't rise up. And so they did. ... We must not let our private, personal selves off the hook."

These words were particularly powerful for me. I was thinking: Are we growing elephant skin on our sensitivities, on our ideals, our virtues? Is inhumanity taking the place of healing one another humanly? I don't want to let any of us "off the hook." We need to reach out and make a difference.

[Carol K. Coburn is a professor emerita of religious studies and director of the CSJ Heritage Center at Avila University.]