Sr. Winifred Doherty of Ireland, left, and Sr. Teresa Kotturan of India (GSR file photos)

Editor's note: This is one in a series of stories about Catholic sisters' advocacy at the United Nations.

September is something of a "United Nations month," when world leaders gather to address the U.N.'s General Assembly in New York and the world focuses, very briefly, on the world's largest intergovernmental organization.

Founded in 1945 in the wake of the embers of World War II, the United Nations is dedicated to global cooperation, peace and security, human rights and, through such programs as UNICEF and the World Food Program, providing humanitarian assistance.

The U.N.'s work has often been met with criticism, ranging from charges that it is too political; favors or disfavors certain countries; that its work is stymied by a lumbering bureaucracy; and that superpowers like the United States and Russia yield too much power and sway, particularly over the U.N. Security Council.

What is often not appreciated by outsiders is that the United Nations is also a global forum, where world issues and concerns of the day — like the climate crisis — are debated, with the hope that change will result. The debates usually occur among the U.N. member states; the hope for change often comes from civil society, and nongovernmental groups who are there to advocate for positions they hold dear.

Among those advocating for the causes of peace, economic justice and the rights of women and children are Catholic sisters representing their respective congregations.

There are 15 sisters active in the ministry of advocacy at U.N. headquarters in New York, and two of the most prominent "veterans" in recent years were Sr. Winifred Doherty of Ireland, who represented the Good Shepherd International Justice and Peace Office at the U.N. from 2008 to 2024, and Sr. Teresa Kotturan of India, who served as U.N. representative of the Sisters of Charity Federation from 2014 to 2023.

Though Doherty and Kotturan are now retired from their U.N. work, with both returning to their respective motherhouses in Ireland and Kentucky, they remain passionate advocates for the causes they championed while in New York.

Both love the United Nations; Kotturan credits Doherty for coining the term "Gospel space" to describe the U.N. But in this extended joint two-part interview with Global Sisters Report, the two are not afraid to criticize the United Nations' shortcomings, flaws and challenges. If the U.N. remains a beacon of hope, they say, it is at a crossroads and in deep need of reform.

Global Sisters Report: What is "sister advocacy" at the U.N.?

Doherty: Advocacy at the U.N. is about entering the diplomatic spaces that are there, as well as speaking to U.N. officials, the U.N. secretariats, but maybe more importantly the member states. In entering that arena, you bring the weighty issues of the world as experienced by particular congregations to the attention of policymakers. It's leveraging our expertise, coming from our charisms, and entering diplomatic circles in order to enable a more wholesome and sustainable policy to be developed globally.

Kotturan: It's an arena where we try to evangelize, if you want to take it from that perspective. For us in the Vincentian spirituality tradition, advocacy is taking the side of the poor because seeing the poor and seeing Christ in the poor is our focus — the idea that if people had basic services and benefits, then we could help restore their dignity. Catholic social teaching invites us to advocate on behalf of people living in poverty, for we are all made in the image and likeness of God.

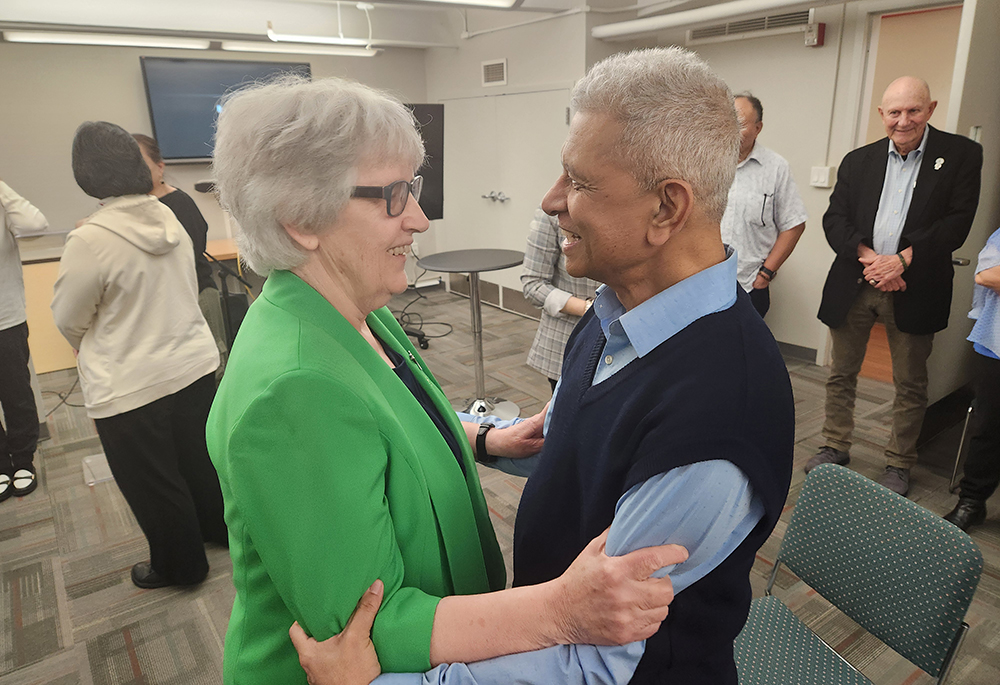

Fr. Rohan Dominic, right, NGO representative of the Claretians at the United Nations, greets Sr. Winifred Doherty at Doherty's retirement party in April 2024. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Explain how the U.N. process works and the significance of holding governments accountable.

Kottaran: Systemic change is what we are working for — advocacy at the U.N. is for systemic change at the global level, when governments sign resolutions we can hold them accountable at the national and local levels.

One example: During the leadup to the SDG [Sustainable Development Goals] negotiations, we focused on getting the phrase "a human right to water and sanitation" in the preamble of the 2030 agenda. Around 700 organizations advocated and we managed to get that phrase into the document. It had a lot of opposition from developed countries because they would be held accountable. But ultimately we were successful.

How easy is it engaging with ambassadors or representatives of country missions?

Kotturan: Engagement with the ambassadors or the missions is not that easy unless they are very friendly or if you come from a country that welcomes NGOs [nongovernmental organizations].

So one example I like to take is in 2017, the Vincentian charism celebrated its 400th anniversary and we made a commitment to ending street homelessness. So then we came together as a small group of five and we formed a working group and were able to push for a theme on ending homelessness for the Commission on Social Development at the U.N. So we got an ECOSOC [Economic and Social Council] resolution in 2020 and a General Assembly resolution in 2021. So those are ways of advocating and finding success. But it's a long process.

Sr Teresa Kotturan poses for a photo on the property of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, Kentucky, in this Aug. 30, 2013, photo. Kotturan served as U.N. representative of the Sisters of Charity Federation from 2014 to 2023. (CNS/Patrick Murphy-Racey)

You've both said that the space for what is called civil society — like sister congregations — has gotten smaller, and that life at the U.N. about a decade ago was more open. Could you unpack that for me?

Kotturan: I came to the U.N. at the end of 2014, and I think that was the golden era of the U.N., when there was openness to receive and hear civil society and our contributions were considered valuable to the process. And that extended to the whole migration and refugee documents that were being debated at the time. I remember making statements at every opportunity we had. For example, the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. But it seems that era has been closed.

Why is that?

Kotturan: Because multilateralism and global solidarity have been brushed aside. The focus is now on nationalism. Lack of reforms at the U.N., especially in the Security Council structure, has created power imbalances. Focus is not on global solidarity, but on transactional relationships. Reliance on corporations for financial support for the U.N. has diluted its ability to keep its eye on "We the People."

Doherty: My frustrations in the post-SDG era had to do with a neo-capitalistic approach really taking hold. I believe that began with the bringing in of the corporate sector into the U.N. That began with the U.N. Global Compact in 2000, when the U.N. embraced the business sector as indispensable for the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs]. That was a moment of diluting something of the desire for a better world.

Good Shepherd Sr. Winifred Doherty, who served as her religious congregation's U.N. representative, speaks about human trafficking at the U.S. Capitol in Washington in this May 15, 2018, photo. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

What has happened is that the corporate sector now has more influence than ever, and nobody is being held to account. The neo-capitalist model is concerned with privatization and deregulation and the "baseline" is profit. Often such practices violate human rights, violate labor rights, prevent unionization and in the case of mining engage in exploitation of child labor, land grabbing, deforestation and in practices that are harmful to the environment.

So, there is a needed critique of companies failing to fulfill commitments to sustainable development targets. Agribusiness is often in conflict with sustainable methods of farming, food production and local food security.

There is this almost global dragon dragging the world down, whether it is the financial sector or the war sector.

Advertisement

The image of 'Gospel space' is interesting because I know some believe that Catholic social teaching, the tradition and ministry of congregations really infuse the U.N. itself and the SDGs, for example. It's not overt, but sort of "baked into" the U.N. ethos.

Kotturan: If you read any of the past or present U.N. documents, analyze the word choices, the phrases, the language used, you see the influence of the Gospel language and values, and Catholic social teaching — upholding the dignity of people — is infused in it.

It's not overt language. But the men and women who helped create the United Nations after World War II, most of them came from a Christian perspective. They brought with them language that was grounded in the Christian tradition.

Doherty: I agree. In my own congregation, people would ask, "What difference does the U.N. make and why is our presence there important?" I came up with the term "Gospel space" to put into the minds of our members that this isn't alien to who we are as Religious of the Good Shepherd. It's actually the "Gospel space." And it's the "Gospel space" in that we are able to sow the seed.

Did you use overtly religious language when you were advocating?

Doherty: I always refrained at the U.N. from ever directly quoting Catholic social teaching. Now, once I say that I'm a member of the congregation of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd, I am acknowledging publicly who I am. What I am doing is informed by what's deepest within me, which is of course the Gospel and the Beatitudes and the corporal works of mercy.

But I didn't take that approach in terms of doing advocacy. I would take what would be more the social-political approach. What we're trying to say is not to emphasize charity as a handout thing but rather evoke rights-based language — the idea that all people have rights to a dignified life.