Carmen Jiménez explains to visitors the Comuna 13 cemetery's wall of portraits honoring victims and their mothers. Among them are haunting composite images: half the face is that of a missing son or daughter, the other half their grieving mother — their features fused into a single, powerful symbol of loss and remembrance. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Carmen saw me before I saw her. "Tracy!" she called out from the hustle and bustle of San Javier Metro Station. Looking much younger than her 49 years in her baseball cap with the feminist lavender raised fist, she smiled and embraced me as if she'd known me for years.

Carmen Jiménez is much more than a tour guide. She has had a certain destiny since 2002 when her younger brother, Guillermo, set off for high school and never came back. She became one of thousands of buscadores, or searchers, people who look for clues of the whereabouts of loved ones they say were forcibly disappeared, and rarely find them.

She is also a proud member of Women Walking for Truth and Women United for Dignity, two collectives of women searching for disappeared loved ones, and identifies as a religious social activist working with Sr. Rosa Cadavid at the Madre Laura Montoya Foundation.

"I've been a religious social leader for more than 30 years here in Comuna 13," she told me.

"My father brought us here when I was almost 4 years old," she explained as we climbed upward through the steadily ascending urban landscape. "There were only about seven families then, no electricity, no water."

The mountains around Medellin transformed in the 1970s and '80s as waves of conflict-displaced families settled the steep hillsides. Like many community patriarchs, her father became a local leader, organizing neighbors to build their own homes, improvise electrical connections and create water systems — developing a self-sufficient infrastructure when the government provided nothing. This grassroots organizing would become a defining characteristic of the community, a resilience that would later be tested by decades of violence.

This same resilient spirit sustained Comuna 13 through the darkest periods: Pablo Escobar's reign, subsequent drug cartel wars that made Medellín the world's murder capital in the 1990s, and the brutal 2002 military operations that families say left hundreds disappeared. From this trauma emerged transformation. Residents channeled their pain into powerful street art and community organizing, while city officials launched their progressive "social urbanism" movement. The iconic outdoor escalators and cable cars became the showcase of this initiative, designed to spur investment and connect the isolated comuna with the rest of the city.

What followed was an unexpected tourism boom that brought constant traffic, noise pollution and gentrification, with outsiders often profiting from the neighborhood's painful past. Carmen and other community leaders work tirelessly to preserve the painful history that most visitors remain unaware of as they dance atop the ghosts of Colombia's darkest chapter.

A tourist bounces on a bungee trampoline on a boardwalk-like strip at the top of the hill in Medellín, Colombia. In the background lies La Escombrera, a massive industrial city landfill where human rights organizations and families say hundreds of bodies are buried. Forensic excavators in December found the remains of four bodies at the site. (Tracy L. Barnett)

My tour began in earnest at a stone wall lined with neat rows of plasticized photos, some decorated with bunches of flowers or ribbons. Carmen pointed to a black and white photo of a small boy: her brother.

"This is him, Guillermo León Jiménez Monsalve," she said softly. "We don't have many photos because he didn't like having his picture taken. Now that I'm working with memory, I see how important photos are."

We have arrived at "Memoriales de las Ausencias" ("Memorials of the Absences"), created by a local artist collective called AgroArte. "What's beautiful about this wall is that there are both victims and perpetrators here," Carmen said. "What I value is that regardless of who we are, there's someone who feels pain when we're not here, whether because we're disappeared or because God has taken us to rest."

She pointed to another boy's photo. "This child belongs to a friend from Women Walking for Truth. His mother is Diana Garza. He disappeared when he was just 9 years old." Her voice broke slightly. "The war here didn't discriminate — not by gender, skin color, nothing. It took children, adults, everyone."

Another brother, Héctor, was shot by a stray bullet while watching television at home, she said, and masked men in black put a gun to her head when she tried to reach him. "I told them they'd have to kill me because my brother was injured and there was no one to help him," she said.

Carmen Jiménez points to a collage of photographs at Museo Comuna 13 in Medellin, Colombia. Images of military operations, protests and mourning families line the walls of the museum, where survivors process the trauma of Medellín’s armed conflict and preserve the stories of "the disappeared" — people who remain missing. (Tracy L. Barnett)

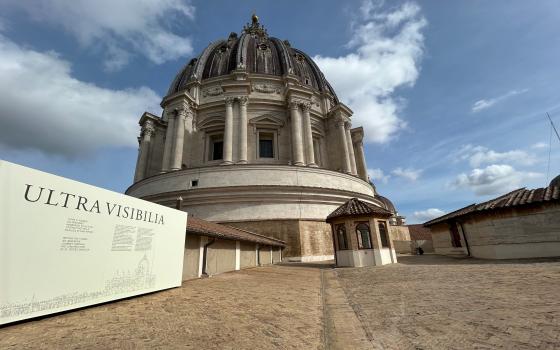

We continued to the cemetery, which Carmen described as "a living gallery in the open air." Transformed in the early 2010s as part of the neighborhood's artistic revival, this once-traditional cemetery now explodes with color. Birds, flowers and faces of loved ones are painted in the spaces between the niches. We passed a wall-sized portrait of a young man with the message, "I don't die if I go away, but if I'm forgotten."

A gently smiling grandmother with the green Earth as her skirt, embracing a crying woman, featuring the phrase "Si no sana hoy, sanará mañana" (If it doesn't heal today, it will heal tomorrow) — a childhood rhyme mothers would say to crying children with scraped knees. In another, a weeping mother lies abed with a photo of her fallen son; behind her, from another dimension, he comforts her.

One thing that stayed with me was the composite portraits — powerful montages where half the face was the disappeared son or daughter, the other half the searching mother, their features melded into one unified image of loss and remembrance.

Graciela's story broke my heart. "When her son disappeared, she began searching for him in garbage cans," Carmen said. "Her mind went somewhere else. She thought her son was in the garbage cans, and she became so fixated on this idea that her mind left this reality. With the work at the Madre Laura Montoya Foundation, they managed to bring her back from that world."

A mural in the Comuna 13 cemetery in Medellin, Colombia, captures the bond between mother and child. "I want to tell you, Mother, that I walk beside you even if you don’t see me," reads the inscription. (Tracy L. Barnett)

As we left the solemn cemetery behind and continued up the hillside, the atmosphere gradually shifted. As we climbed higher, the tourist infrastructure that has intensified since around 2015 became more apparent. Carmen's expression tightened as we entered this more commercialized zone, where history is often glossed over for easier consumption.

Carmen pointed out a museum dedicated to Pablo Escobar, the violent drug lord . "It's hurtful that they're making money glorifying a man who caused so much violence," she said. She told me about a family who reached out to her to help their son, who was idolizing Escobar. She took the boy on a tour, including a visit with her uncle, who was disabled after being shot because Escobar was offering a million pesos to anyone who killed police officers (for which her uncle was mistaken).

"When I showed him my uncle's scars and told him what actually happened, I saw his face change completely — that idol he had built up just collapsed," Carmen recalled with quiet satisfaction.

At the top of the electric escalators, the view opens to flashing neon and tin-roofed homes stacked up the hillside. A tricolor-draped Christ, a massive gorilla and a concrete woman's head, an icon representing a local craft beer called “Origen,”overlook the scene. (Tracy L. Barnett)

The murals here hold powerful stories. A sad child with a jar full of fireflies and a snake looming over her as if to strike; an elephant, representing memory, its tusks draped with white handkerchiefs — symbolizing the women's desperate plea for ceasefire during Operation Mariscal in May 2002, one of the first military offensives in Comuna 13.

"They used them to try and get the dead and wounded out," Carmen said. Months later came Operation Orion, the larger and more infamous assault, depicted in another mural showing hands playing with houses like cards, dated Oct. 16, 2002. "The lights caught my attention," Carmen noted, "because during these operations, we often slept with the lights on out of fear they would break into our houses."

'Regardless of who we are, there's someone who feels pain when we're not here, whether because we're disappeared or because God has taken us to rest.'

—Carmen Jiménez

As we climbed higher, the tourist infrastructure became more intense. Rows of vendors selling souvenirs lined the pathways, many obscuring the very murals that tourists came to see. Chota 13, the famous street artist whose luminous murals brighten the comuna, now has a museum/storefront called Chota 13 Experience, where people line up to see his work and buy his silkscreened designer jackets.

We reached the remarkable system of covered outdoor escalators, a monumental public works project that gained global attention when it was installed in 2011, transforming a grueling 35-minute uphill climb into a six-minute ride — and a forgotten barrio into an international attraction, with an estimated 25,000 visitors per week. The escalators were built without roofs; the community came together to add protection from the rain.

Carmen said the escalators represent both progress and pain. "When we were studying this, we dreamed of electric escalators like in shopping malls. Now we have them, but at what cost?"

And indeed the costs have been high. Gentrification pressures have led to rising rent, outsiders have reaped many of the tourism dollars, and some residents believe that the community's pain is being put on display.

Local organizers like Carmen continue to advocate for tourism that respects the community's history, avoids exploitative practices and reinvests in local people.

Carmen Jiménez pauses at the "Memoriales de las Ausencias" (Memorials of the Absences). She is one of thousands of "buscadores,: or searchers, people who look for clues of the whereabouts of loved ones they say were forcibly disappeared during Colombia's violent past. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Finally, we emerged onto a boardwalk-like strip at the top of the hill, where loud music blasted from restaurants and bars, and from a trio of musicians right in front of us. People danced and drank and snapped selfies. Comuna 13's surreal skyline unfolded around us — monumental sculptures rising from the riot of color and sound. A towering cement-colored woman's head with a gold headband, part of an ad campaign for Origen craft beer, loomed beside a tricolor-draped Christ the Redeemer figure with outstretched arms; and a massive gorilla perched above it all, surveying the scene like a guardian spirit — all set against a backdrop of flashing neon signs and tin-roofed houses painted every color of the rainbow, stacked like children's building blocks up the mountainside.

It was here that Carmen quietly pointed across the canyon to an ugly gray slash in the verdant hillside — La Escombrera, the dump site.

"According to investigations, there are 502 people in La Escombrera," Carmen told me, gesturing toward the landfill visible in the distance. "And many people still haven't reported their disappeared loved ones out of fear."

The juxtaposition was jarring. A man nearby was hawking tickets for a bungee trampoline, with a tourist bouncing joyfully against the backdrop of what is essentially a mass grave. Carmen's mother could see it from their house and would stare at it, tormented by the thought that Guillermo might be there.

"According to witnesses, they would take young men off buses and ask if they wanted to join the paramilitaries," Carmen said. "If they refused, they would make them dig their own graves in La Escombrera."

Advertisement

Standing at the highest viewpoint of Comuna 13, Carmen gazed out over the neighborhood's colorful rooftops and the sprawling city beyond. She winced slightly as she shifted her weight.

"The suffering gets into your bones," she said, saying that the trauma of her brother's disappearance had manifested physically — bone problems, even a cancerous cell years ago. "The pain eats you from inside."

The pounding reggaeton from a nearby bar competed with the laughter of tourists posing for photos, while across the canyon, La Escombrera's gray scar cut through the green hillside. After hours of sharing painful histories and hard-won victories, she turned to me with unexpected gentleness.

"I always say, my weapon is love," she said. "In spite of all those who want to do us damage — I know that we can change."

As we descended the hillside together, her words lingered in the air — a powerful testament to how even the deepest wounds might someday transform into something resembling hope.