Sr. Rosa Cadavid looks at photos of victims of violence at the Madre Laura Montoya Foundation. Foundation volunteers are in the process of reorganizing the gallery that once held the photos of people mourned as victims of violence in Medellin, Colombia. (Tracy L. Barnett)

In a quiet room at the Madre Laura Montoya Foundation on the edge of Comuna 13, a woman taped a faded photograph of her son on the wall. For years after his disappearance, her grief had been a locked room she could not escape. But here, surrounded by other mothers, and by dozens of similar images — faces of the murdered and the disappeared — she found the courage to speak.

"I talk to my son here," she told Sr. Rosa Cadavid. "I say to him, 'My love, I'm here, I'm OK. I've made peace with you. I'm not as bad as I was.' And I feel like he answers me."

From her all-terrain wheelchair, Cadavid coordinates this space of collective memory and healing amid a sprawling convent. The lively green campus of the Madre Laura Montoya Convent, also home to a neighborhood school, serves one of the communities hardest hit by Colombia's devastating civil war, which began in the 1960s.

Cadavid's own brush with death in a 2000 bus accident might have ended her mission but instead deepened it, giving her fresh insight into the pain of those she serves. A member of the Missionaries of Mary Immaculate and St. Catherine of Siena, the energetic 73-year-old follows in the footsteps of Mother Laura Montoya, Colombia's only canonized saint, serving marginalized communities.

Beyond providing a space for healing, Cadavid has forged a formidable path toward justice. "What we initially built was a proposal to work for the victims, to make them visible, to get them recognized, and to tell them the truth," she told Global Sisters Report.

Her work helped create Mujeres Caminando por la Verdad (Women Walking for Truth) in Comuna 13, a dense collection of neighborhoods climbing the hillsides of Medellín's western edge. The group transformed grief into action, overcoming the terror to share their stories and evolving into a force for justice and the search for "the disappeared" — their loved ones still missing after a violent era.

The term "disappeared" refers to people who were abducted or held against their will by state agents and whose whereabouts remain unknown. More than 100,000 people have been forcibly disappeared over the past six decades in Colombia, according to the country's Search Unit for Missing Persons and the United Nations.

The women drew international attention when officials in December discovered the remains of four humans in La Escombrera, a massive industrial city landfill where relatives, human rights groups and official investigators say hundreds of people — mostly missing since the 2002 military operations in Comuna 13 — are buried.

For more than 20 years, the women demanded that the government conduct excavations at the site to find the remains of their loved ones, but were ignored and ridiculed. Their constant pressure and presence at the site yielded results, however, and finally in July 2024, excavations began. In December, when the earth yielded its first remains, the nation was in an uproar. "LAS CUCHAS TENIAN LA RAZON," was the rallying cry: "The mothers were right."

Courage under fire

Cadavid has been courting death for decades, serving in zones of conflict from the lush river valleys of the Medio Magdalena to the rugged, mist-shrouded mountains of Urabá near the Colombian-Panamanian border. Her advocacy of the victims and outspoken opposition to violence have made her a military target at least 10 times, she said. At one point, she said, she was briefly kidnapped, and after the murder of 22 community leaders she worked with, she was forced to flee the country in 1998.

"When the 22 leaders were killed, I learned I was on the hit list too," Cadavid said. "The Peace Brigades began protecting me — but I was unaware of how grave the danger really was."

She had gone to Urabá at a particularly volatile time when paramilitaries had publicly announced their intention to "take Urabá and kill all the guerrillas in the region." To the paramilitaries, everyone was a suspect.

"Just wearing boots or having calloused hands — completely normal for campesinos — was enough to mark someone as a guerrilla," Cadavid said. Even those working to support peace became targets.

Despite these dangers, she helped establish the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó. Her work there included negotiating with armed groups for safe passage to deliver food and supplies to isolated communities. On one harrowing occasion, her truck of food was stopped by 80 paramilitaries with rifles pointed at her.

"They labeled me a guerrilla just for bringing food," she said. "I insisted: 'I'm no guerrilla. Call your superior. Search me.' " They let her pass.

Once an epicenter of Colombia’s armed conflict, Medellín’s Comuna 13 is now a symbol of resilience and transformation. From this quiet residential street, the densely packed hills of the comuna unfold — home to a community that has endured violence, displacement and military operations, and today pulses with art, activism and hope. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Sr. Rosa Cadavid takes a quiet call in the covered walkway of the Santuario de la Madre Laura, a sanctuary she calls home. Designed by Colombia’s first canonized saint, the space offers peace and reflection on the edge of a community long marked by conflict. (Tracy L. Barnett)

As if guided toward Colombia's most troubled regions, Cadavid was assigned to minister in Comuna 13 in 2001, just as this Medellín neighborhood was emerging as another flashpoint in the country's conflict. It was a pattern familiar to her congregation — where violence flared, Cadavid seemed destined to follow.

Operation Orion

In 2002, newly elected right-wing President Álvaro Uribe Vélez launched an aggressive nationwide campaign to eradicate guerrilla presence. Comuna 13 became a primary target.

For two years, residents endured increasingly violent confrontations between guerrilla groups, paramilitaries and government forces, culminating in Operation Orion, the largest urban military operation in the country's history. These assaults deployed thousands of troops, tanks and helicopters against Comuna 13. What was framed as an effort to flush out guerrilla fighters became, in the words of residents, a massacre.

"There were horrible disappearances," Cadavid said. "Collective assassinations, sexual violence against women, kidnappings, displacements — every form of aggression carried out with the permission of the public forces and the authorization of the state."

Young people were heavily targeted, many because they refused to be recruited or collaborate with the drug trade, said Fr. Wilfred Weber, a German priest who worked closely with Cadavid in those years. Her ministry created a ripple effect through her accompaniment of women, her presence in community meetings, and her ability to bring comfort and calm in moments of collective trauma, he said.

"I would say that Sister Rosa's work changed the neighborhood," he added.

Sr. Rosa Cadavid laughs with Fr. Wilfred Weber, a German priest who has accompanied communities in Colombia for decades. Their friendship was forged through years of shared service during some of the country's most difficult chapters. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Even before Operation Orion, Cadavid had begun organizing women through Mujeres Sembradoras de Esperanza (Women Sowers of Hope), focused on the first wave of forced displacements. Their strategy was territorial resistance — taking over public spaces like the canchas (soccer fields), organizing community events and refusing to abandon their homes despite mounting pressure. These acts of collective defiance made them targets; some were falsely accused of guerrilla ties, had their homes raided and were publicly defamed.

In the aftermath of Operation Orion, when armed groups still controlled the neighborhood, everything changed. The leadership of the women’s Sembradores group had been decimated, and the community was paralyzed by grief. Some 500 residents of Comuna 13 had been reported as forcibly disappeared — among the nearly 6,000 missing persons reports for the city of Medellin.

"What we had to do changed: now what we had to accompany was the pain," Cadavid said.

The sister began reaching out to mothers who had lost children. Initially, women were afraid to speak about their experiences. "They had too many fears," Cadavid said.

A diorama depicts La Escombrera, transformed to a place of life and memory. (Tracy L. Barnett)

In this environment of terror and trauma, Cadavid developed an intuitive approach to healing. "Here, you learn to be a psychologist," she said. "Practice teaches us how to deal with people's pain. But after so many years of accompanying people through suffering, you come to understand that one essential element is knowing how to listen."

Through painting workshops, textile creation and memory books, women processed their trauma together. For Nancy Zavala, a breakthrough came when she painted the landscape of the family farm from which her family was evicted when she was a child. "It's like healing the soul," she said. "The sadness ... one learns to live with that, but now without resentment; that is healing."

A "botiquín de memorias contenidas," a symbolic first-aid kit created in a healing workshop, includes salves, pills and bandages labeled with words like "truth," "justice" and "reparation." (Tracy L. Barnett)

But healing was just the beginning. As the women found their voices, they renamed themselves Mujeres Caminando por la Verdad (Women Walking for Truth), reflecting their new purpose — demanding answers about their disappeared loved ones.

With nothing left to lose, the women took their collective pain public — walking in protests, planting crosses, holding encampments at La Escombrera and speaking to the media. Their persistence forced institutions that had long ignored them to finally listen. When they received a human rights award in 2015, their declaration captured this transformation: "We have won the word, we have come out of the silence to which we were subjected ... and today we raise our voice for the rights of all victims."

La Escombrera

For more than two decades, Women Walking for Truth fought to excavate La Escombrera, only to face repeated government denial and ridicule.

"Part of the victimization of Comuna 13 is being relegated to oblivion," Frankly Alberto Suárez, who works with Cadavid at the foundation, told GSR. "The government and the state are saying that no violence happened here, that there are no buried people, that there are no dead, that nothing happened. It's state negationism."

Yet the women refused to let the dead be forgotten. They held vigils and planted symbolic silhouettes across the hillside, transforming La Escombrera into a sacred landscape of memory — an act of resistance that reclaimed territory the state insisted was empty.

Advertisement

Their persistence sparked wider action. Testimonies from former paramilitaries — some obtained through the peace process — identified La Escombrera as a site of clandestine burials. In 2020, Colombia's Special Peace Tribunal, or JEP protected the site from ongoing construction excavation and, with support from the government's search unit and human rights organizations, finally dispatched forensic investigators.

In December 2024, La Escombrera made international headlines when excavations revealed the first human remains.

"When they found the first bodies, they felt several sensations," Cadavid said. "Joy of having found something — because it was always said that nobody was there, that they were imagining all this — but also feelings of sadness, of pain."

Undeterred, these women continue their fight for truth. Their success has inspired Cadavid to form a new group, Women United for Dignity, comprising victims who had remained silent until now.

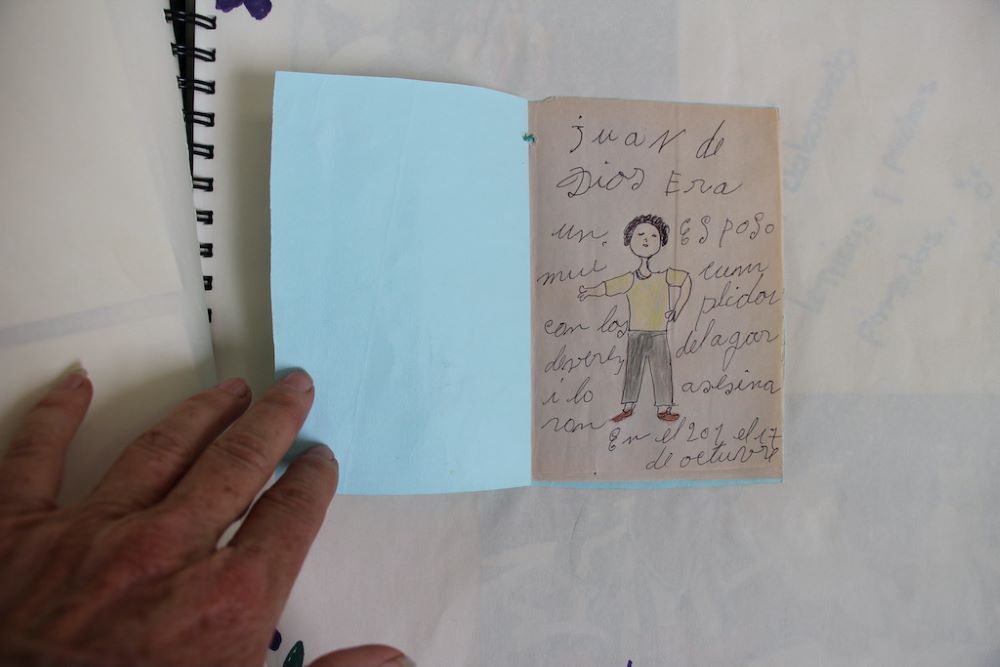

Sr. Rosa Cadavid holds a booklet a woman made to honor a devoted husband, Juan de Dios. Juan of God is a common name throughout Latin America. (Tracy L. Barnett)

For women like Carmen Jimenez, longtime activist with Mujeres Caminando por la Verdad, Cadavid has been both anchor and compass through decades of trauma. Jiménez still remembers the transformative moment they first met.

"I'll never forget when I arrived at the convent and Sister Rosa in her wheelchair opened her arms to me," she said. "With that hug that I needed — a hug not even my mom had given me — I fell in love right there. I fell in love with that woman."

Today, Jiménez is among those carrying forward Cadavid's legacy. As a tour guide in Comuna 13, she reclaims the neighborhood's narrative while searching for her brother, Guillermo.

"I show tourists my brother's photo and tell his story, hoping someone might recognize him, that he'll know we haven't forgotten him," she said.

Despite her loss, Jiménez maintains hope.

"What gives me hope? People like Sister Rosa, and the children being born now," she said. "I see my grandson and I think, what will we leave them?"