Filmmakers Jillian Schultz, left, and Leah Thompson discuss their upcoming documentary on Corita Kent, "You Should Never Blink," during the History of Women Religious Conference in Notre Dame, Indiana, June 23. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

After fleeing the Cuban Revolution in the 1950s, the congregation that would become the Poor Clares of Brenham, Texas, found themselves free to carry out their mission but nearly penniless.

They tried several ventures, said Selena Aleman, archivist for the Catholic Archives of Texas. But none worked. Aleman presented the results of her research on the Cowboy Nuns of Cuba at the History of Women Religious Conference, held June 22-25 in Notre Dame, Indiana. Themed "Lives and Archives," the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism's 13th triennial conference brought together about 150 archivists, historians and researchers.

The Poor Clares tried raising and selling parakeets, Aleman said, and then Himalayan cats. But when Sr. Bernadette Muller suggested they raise miniature horses, they struck gold: Their tiny horses gained national attention, were competitively exhibited and sold for up to $5,000 each.

But by 2010 the congregation was down to three sisters, the horses were sold off, and the monastery was dissolved in 2013. The property is now a retreat center for the Pax Christi Sisters.

As congregations in the United States see their numbers declining, many are realizing the need to preserve their history and are turning to professional archivists.Without archival material, stories such as the Cowboy Nuns of Cuba would be lost.

If they don't tell their story, "sisters are writing themselves out of history," said Michele Levandoski, president of the Archivists for Congregations of Women Religious.

The vast majority of women's congregations have an archive staff of one; 60% have no digitization, and more than one-third are not open to the public, said Veronica Buchanan, executive secretary of ACWR. The organization, incorporated in 1993, has more than 200 members since.

"You can easily see why the story of women religious in the United States is often unknown to historians," said Buchanan, archivist for the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati.

But it's also understandable when leadership is dealing with challenging decisions on missions, land and buildings, and must put the care of sisters before all else, she said.

The challenges will continue to grow even as the need increases, said Levandoski, archivist for the School Sisters of Notre Dame North American Archives. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University, there are less than 35,000 sisters in the United States, down from more than 57,000 in 2010 and from its peak at nearly 179,000 in 1965.

"There's going to be less one-on-one dialogue with sisters, and therefore less knowledge of their activities" as their numbers get smaller.

Stories to tell

The conference examined plenty of historical knowledge and sister-led work: 86 papers were presented, exploring topics that included how Indigenous sisters were left out of the histories of some European congregations, while another looked at how the histories of some Indigenous congregations left out the European sisters who ministered with them.

The evening of June 23, attendees got a sneak peek at a forthcoming documentary on Catholic sister and pop artist Corita Kent. Kent was a Sister of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, but left religious life when the congregation split, with some sisters remaining and others forming the ecumenical Immaculate Heart Community. Kent was commissioned to create a banner for the Vatican pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair, was on the cover of Newsweek in 1967 and created the 1985 "Love" U.S. postage stamp. She died in 1986 at age 67.

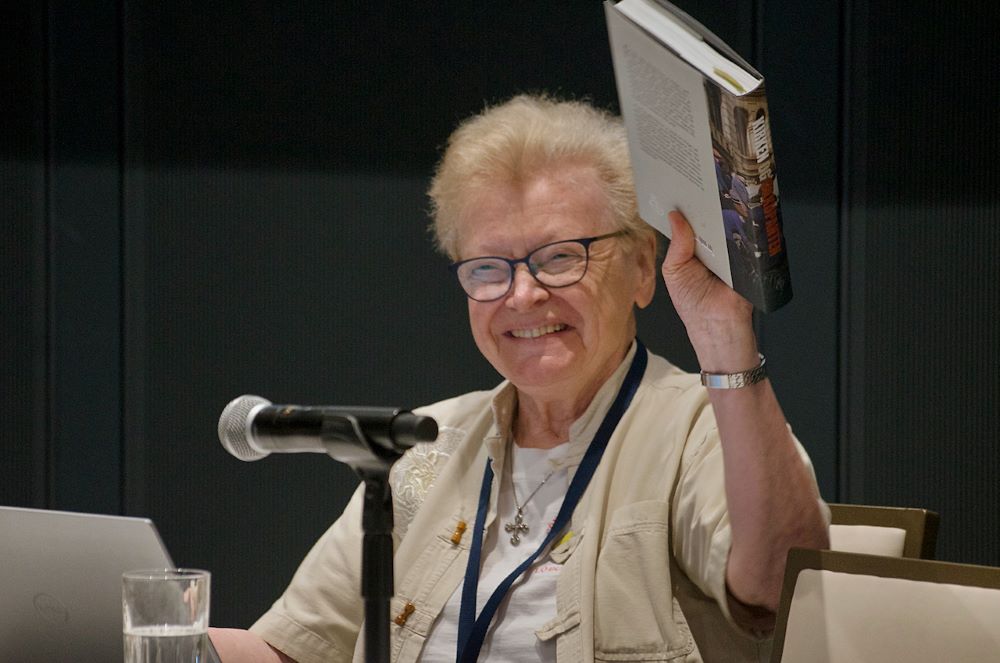

Sr. Else-Britt Nilsen, prioress of the Dominicans of Notre Dame of Grace in Norway, holds a copy of her book, "The Church and the Occupier: The Catholic Church in Norway and the Second World War," June 24 during the History of Women Religious Conference in Notre Dame, Indiana. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Filmmakers Jillian Schultz and Leah Thompson showed a preview of their film, "You Should Never Blink," but said completion has been delayed because the federal Department of Government Efficiency slashed funding for the National Endowment for the Humanities.

"We lost $350,000 in funding," Schultz said. "We went from being about 85% funded to going back to square one, which is especially difficult since we're already in production."

The film had been due for release later this year; they said it is now planned for mid-2026, and is slated to be part of the PBS "American Masters" series in 2027.

One presentation looked at how examining the past — even the painful past — can bring healing. Arlene Bachanov, an associate with the Adrian Dominicans, and Sr. Mary Navarre of the Grand Rapids Dominicans, said both congregations knew they had once been one, but no one living knew why they split.

"Everyone had their own idea of how this came to be," Bachanov said. "There were all sorts of assumptions out there about what happened. …Who initially instigated the split depended on who was telling the story."

But their research — despite challenges such as missing documents, damaged paper and indecipherable handwriting — found that Henry Joseph Richter, the then-bishop of the newly-formed Grand Rapids, Michigan, diocese, wanted a diocesan congregation of his own. In the 1880s, Richter forced half the Dominican sisters in Grand Rapids to move to Adrian, in the Detroit diocese, they said. The Adrian sisters officially became an independent congregation in 1923.

"How many of you are surprised a congregation of women religious had their lives changed by a male cleric?" Bachanov asked. "This was very painful for the sisters."

Navarre said it was especially difficult for the sisters sent to Adrian, a tiny town surrounded by corn fields.

"Suddenly they found themselves alone," she said.

The congregations have grown closer over recent decades, but Bachanov and Navarre's work, collected in the book, Golden Links, has brought them even closer, they said.

Advertisement

Presenter Mary Carney, a professor at the State University of New York at Fredonia, didn't set out to research women religious at all — she just wanted to make a family tree. Then she discovered that her grandfather, Patrick "PJ" Kieran, stole $5 million from congregations of nuns and priests. He spent three days in jail for his crimes, while the congregations spent years or decades paying off their losses, Carney said.

She said her research in newspapers from the era and religious congregation archives found that starting in 1905, when Kieran became a partner in the Fidelity Insurance Co. in Buffalo, New York, he began loaning money he didn't have to religious congregations for building projects, using funds like a shell game until it collapsed in 1908.

Religious were paying off the debt until the 1920s, Carney said, but just as Kieran's crimes were a family secret no one talked about, Carney said getting swindled has remained a sort of family secret for the congregations that got ripped off. She said she read hundreds of court documents trying to piece together what happened.

Sr. Simone Campbell on history to avoid repeating

To close out the conference, Sr. Simone Campbell delivered a rousing speech June 24 at the banquet address, proclaiming that now is the time to listen to our faith, cast off our fear, and stand up against a rising tide of fascism.

Campbell — who led the Catholic social justice lobby Network for 17 years, began Nuns on the Bus and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom — said she and the other American sisters in her congregation were inspired by their sisters in Hungary, who endured four decades of Communist oppression. Many of the Hungarian sisters served prison terms, including Sr. Judith Fenyvesi, who served almost 13 years in prison, most in solitary confinement. (Fenyvesi converted to Catholicism while her Jewish family died in the Holocaust.)

Sr. Simone Campbell, a Sister of Social Service who began the Nuns on the Bus tours, delivers the banquet address June 24 at the History of Women Religious Conference in Notre Dame, Indiana. (GSR photo/Dan Stockman)

Campbell, of the Sisters of Social Service and a National Catholic Reporter board member, said the Hungarian sisters told them that fascism rises because of fear, and fear gives it its power.

It's a history she doesn't want to see repeated.

"We never agree on anything, but after hearing from our Hungarian sisters, we agreed 100% that we will not be silent," she said, adding there is no time to waste. "Faith calls us to this moment. We are the people we've been waiting for."

But people can't be afraid of breaking the rules if the rules are wrong.

"It's not about doing the nice thing, it's about doing the right thing, the thing that people need," Campbell said. "The key for me is, how do we use this moment for mission?"

Campbell praised the work of the archivists and historians, but said it's not really about women religious.

"What you study is really the movement of the Holy Spirit," she said. "We're just the ones who get to do the work."