My brother Nicola and I help our dad blow out birthday candles. (Provided photo)

Editor's note: Notes from the Field includes reports from young people volunteering in ministries of Catholic sisters. A partnership with Catholic Volunteer Network, the project began in the summer of 2015. This is our 11th round of bloggers: Celine Reinoso is a Loretto Volunteer in El Paso, Texas, and Maria Longo is a Notre Dame AmeriCorps volunteer in the Bronx, New York.

One of the most difficult and altogether beautiful things about serving young children from the South Bronx is that they are entirely transparent. If they love something, you can see it in every part of their being — their smiles, their words, their laughter, their curiosity. If they hate something — you, for instance — you will know within seconds and will be reminded almost constantly afterwards until the sentiments change.

However, I must point out that, more often than not, it isn't you they hate. Not at all. Rather, the anger that sparks and spreads rapidly is directed at whatever is in front of them and very rarely finds its origin in them. No, my suspicion is that the anger — not pettiness or frustration over "you touched my stuff!" but raw, real, unadulterated emotion — comes from hurt within the home.

I have seen this manifested in the 7-year-olds who come to school docile with sleep and then start throwing chairs within the hour when they fully wake. The malice begins to radiate from them, and they lash out at anyone and everyone because that's all they know outside of school. And who can blame them? Some don't eat if they aren't at school, and they're barely at the age of reason.

Advertisement

I also attribute a major cause of this phenomenon to the sad fact that many of my students lack father figures in their lives. There is a power that man holds in his movement and being that woman cannot imitate. While women embody the merciful love of God, it is men who live the justice of God's law so well. My own life is a testament to this.

When I say that I was "blessed" as a child, what I really should be saying is that I was loved abundantly. I was doted on, highly praised, and given everything that I wanted within reason. I wanted for nothing, not even Christ. I am a cradle Catholic, born to a richly Italian American family that firmly settled in the United States just a generation or two ago. I had a strong paternal upbringing in a fiercely patriarchal household led (presumably) by God the Father, then by my own father, and then by his fathers after him.

Richard Jackson,"Papa," my mother's father, in military uniform (Provided photo)

My mother's father — "Papa," we call him — was a West Point graduate and a military officer for years, serving in the Korean War and leading his wife and five children into the daily battles of the modern world. He is in every way a gentleman and a leader, logical, even-tempered, and desirous of virtue. My Nonno, my father's father, is head of house in a very different way. While he doesn't embody the reputation and rigidity of "Papa," he offers that same goodness in a different lens.

Much like Papa, he was a military man — and first and foremost a man of God — but before all that he was a sneak and a cheat and the most mischievous little rascal to ever terrorize southern Italy. He matured young under the wrath of his own father, working on the family vineyard before finding a love for teaching, a knack for tinkering, and job with the Italian Air Force.

This brought him to his wife and opened the door to America, where he and Nonna finally settled after bearing my father and living on the Italian Mediterranean for five more years. While Papa instructs with graph paper and pencil, Nonno gives funny little trinkets and accompanying parables. While Nonno teases and heals with laughter, Papa smiles gently and offers a firm hand to hold. These two identities helped form the person that I know as my own father.

Dad is a lot of things. He is a social butterfly. He loves to talk and make connections and offer whatever he can to another person. He is slow with words and pauses often while speaking. This annoys some people — namely my mother — but I believe it is because he desires to only say exactly what he must and in exactly the way he means.

He has, however, become quick to forgive, and perhaps this is due to his acknowledgement that he himself has made so many mistakes. Every Saturday morning, I would wake to the smell of coffee and bacon. Once I was old enough to have my own bed, I would fly from my mattress and rush into the kitchen to find him standing at the stove, preparing for the glorious tradition known as "Pancake Day." I would chase myself around his legs and cause quite a commotion until he and my mom sat me down at the table to devour a massive breakfast.

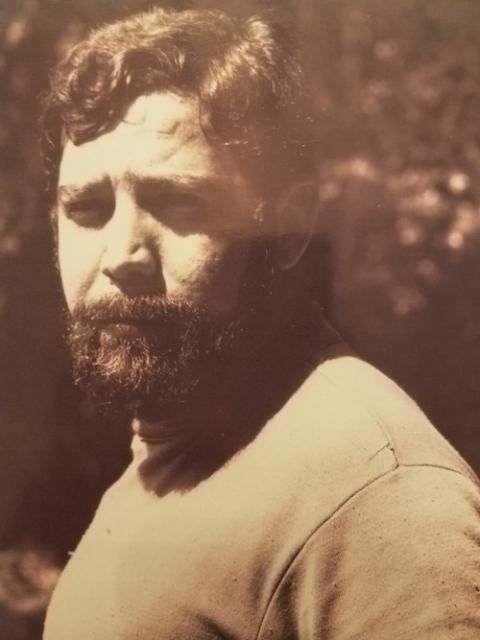

Nicola Longo, "Nonno," my father's father (Provided photo)

The communion — beginning with Pancake Day — continued the following day when Dad drove the family to our local parish for Sunday Mass. While Mom brushed my hair and kissed my cheek and fussed over me, it was Dad who I was looking at. It was Dad who flipped the pancakes. It was Dad who kept hold of my hand even after the Our Father was over. It was Dad who held me up so I could see what was happening on the altar. Mom loved me for all my scrapes and shortcomings, but Dad validated me and called me to something higher. If Mom was the beauty, Dad was the truth. If Mom was the warm fire, Dad was the sturdy hearth, and I basked in their glow.

It is due to their diligence and sacrificial love that I know the Father and find myself in him. And my heart bleeds for the student who weeps in my arms because he doesn't know how to control his anger and doesn't have a "God" or father in his life. All I can do is love as best I can, pray and trust that the Lord will provide the rest. I can nurture my own faith, I can show it to my students — live virtue, attend the sacraments, teach church doctrine — but what I should also be striving to do is to offer them the opportunity to hope.

Yes, my mission is to catechize, but even if a person has great faith and knows that great love is waiting in heaven, he is lost if he lacks hope, for hope is the thing that bridges the two and connects this finite moment with all eternity. All this I learned from my father and his fathers. In them, I find good counsel. In them, I see mistakes and victories. In them, I recognize that I am loved. In them, I know Christ.

[Maria Longo serves with the Notre Dame AmeriCorps program in the Bronx, New York. Because of COVID-19, she is currently working from her family home in Powder Springs, Georgia.]