The outpatient clinic circa 1940 at Mercy Hospital (now Mercy Medical Center) in Baltimore (Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

The Sisters of St. Francis of Rochester, Minnesota, haven't run St. Marys Hospital, which they founded in 1889, for nearly six years, but they say the Franciscan charism at its heart is still going strong.

Sisters across the United States have dealt with this issue for decades as their numbers have declined and health care has changed: As fewer sisters are involved, how do you ensure the enterprise stays true to its original mission?

The Rochester Franciscans have worked to answer that question at St. Marys since the hospital became a sponsored ministry in 1986 and sisters moved out of day-to-day operations. In 2014, it was subsumed entirely into Mayo Clinic, but instead of disappearing, the sisters' values expanded to the entire Mayo organization.

"The leadership of our institution, in partnership with the leadership of the Franciscan sisters, wanted the total protection and perpetuation of our Mayo and Franciscan values, not just at St. Marys but all throughout Mayo Clinic," said Dr. Robert Brown, a Mayo neurologist and director of the clinic's Values Council, which reports to the board of governors and ensures those values never fade.

"The sisters were so integral to the existence of St. Marys Hospital and Mayo Clinic. We could just never lose those connections," Brown said. "It really helps inspire and guide us."

As sisters age out of active ministry, many congregations have faced questions about how their ministries' values will continue after the sisters are gone or after they are no longer affiliated with the founding communities. In the 1950s, it would not have been uncommon to find sisters holding almost every position in the hospitals they had. Now, you might find sisters only in executive positions, on the board or in historical photos.

"The sisters in the 1970s recognized the declining numbers of sisters, and at the same time, they recognized the talent and the concern of the laypeople who were taking over for them," said Sr. Carol Keehan, a Daughter of Charity and the former president and CEO of the Catholic Health Association. "Of course, the concern then was not so much about charism as it was about Catholic health care."

Advertisement

The term in those days was "mission integration," said Sr. Mary Haddad, a Sister of Mercy and the current CHA president and CEO.

"As leaders realized there were less sisters around, they wanted a way to ensure the mission was a part of everyone's life, no matter their role," said Haddad, who previously oversaw sponsorship, mission, ethics, leadership formation and learning integration for CHA.

Keehan makes a distinction between charism and mission, noting that while each religious community has its own charism, just as each person has their own personality, all involved in Catholic health have the same mission.

"Charism is a gift of the Holy Spirit to the church," she said. "But this is about living out the mission."

Expanding the charism

How to ensure the charism doesn't fade at St. Marys Hospital in Rochester is not a new question. The hospital was started in 1889 in partnership with Dr. William Worrall Mayo, who opened a clinic to supply doctors to the hospital. That partnership, based only on a handshake, lasted 97 years. In 1986, the hospital became a "public juridic person," an entity recognized by the Catholic Church, and a sponsored ministry that sisters oversaw more and more on the sponsorship board rather than through day-to-day care. That allowed it to integrate with another hospital and with the Mayo Clinic, which still supplies the doctors to both.

St. Marys Hospital merged with Mayo Clinic in 2014. But though St. Marys Hospital as a separate enterprise no longer exists, the charism has expanded to the entire Mayo system, which includes campuses in Arizona and Florida, and the Mayo Clinic Health System, which covers 60 clinics and hospitals in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Iowa.

A surgery at Mercy Hospital (now Mercy Medical Center) in Baltimore, circa 1920 (Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

At St. Marys after the 1986 integration, that responsibility of maintaining values first fell to Franciscan Sr. Mary Eliot Crowley.

"My role was to set up education programs [on the values] throughout the hospital and to set up values reviews, where we looked at each department in the hospital to see how they were carrying out those values," Crowley said. "They were on about a three-year rotation. Every year, we'd go back and check their progress on things they said they were going to improve on, but every three years, they got a full review."

She ensured the hospital maintained its Franciscan values for 27 years until the 2014 merger, when the sisters' sponsorship board was replaced by the Mayo Clinic Values Council.

"The lynchpin of our values is how we understand and do teamwork," said Franciscan Sr. Tierney Trueman, who serves as the Values Council coordinator for Mayo Clinic. "I think we're in an extraordinarily unique situation here."

A key part of forming leaders in Catholic health systems who embrace and live those values is an annual pilgrimage.

Sr. Jayne Helmlinger, a Sister of St. Joseph of Orange, California, and president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, has been leading annual trips to Le Puy, France, for St. Joseph Health officials since 2008, despite stepping down from her mission integration role there in 2011. The order was founded in Le Puy in 1650; pilgrims see the original convent, the place where Jesuit Jean-Pierre Medaille called them to service, and the place where sisters were guillotined in the French Revolution.

"I love to connect people to our mission: 'I don't care what religion you come from; here is ours, and it's all about the healing ministry of Jesus,' " Helmlinger told GSR. "People from all faith traditions loved it and were able to connect the mission of St. Joseph Health to whatever their tradition was. You just saw people blossom in their own spirituality."

The Catholic Health Association offers pilgrimages for congregations that don't have their own. In May, the group took 50 lay health executives and administrators from CHA hospitals to Rome to learn about their role as laypeople in a church ministry and their responsibility to the church and religious congregations.

Mercy Sr. Karen Schneider, a pediatric emergency medicine physician and assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, during a recent medical mission to Haiti (Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

Deborah Proctor, the former president and CEO of St. Joseph Health in California who made the pilgrimage to Le Puy, said the sisters and their values had such an impact on her over her career that she eventually became Catholic herself.

"It really is an incredibly moving moment for our leaders to have that connection" to the sisters' legacy, Proctor said.

Formation and Transformation

Today, "mission integration" is giving way to "formation." Many larger health organizations have their own formation programs run or overseen by sisters. Others can use formation programs run by CHA.

The CHA Sponsor Formation Program has participants meet during weekend sessions over 18 months, where they blend prayer and ritual, presentations, small and large group activities, and personal reflection. Its Foundations of Catholic Health Care Leadership program has in-person or online sessions on key theological principles, ethics, mission and ministry leadership.

"Formation really moves toward the transformation of the person, which ultimately affects the transformation of the organization," Haddad said. "And it's not just CHA delivering these programs. Our members have created their own formation programs. That underscores the value they put on this."

In the beginning, no one knew for sure how to do mission integration, so programs concentrated on the history and tradition of the founding congregation, and it was often part of new employee orientation or part of departmental retreats, Haddad said.

"Prior to the 1990s, this was all in its infancy stages," she said. "Often times, it was sisters running those programs, and they were chosen because they had been in educational ministries" rather than because they had an expertise or experience in the role. "It was sisters who had never done it before, but it was just assumed that because you're a vowed religious, you can do this work."

Not anymore.

Mercy Sr. Helen Amos speaks at an Oct. 22 gathering of Catholic Charities of Baltimore. Amos was the recipient of the Msgr. Art Valenzano Joyful Servant Award for her role as chair of the Leadership Advisory Group for Baltimore's 10-year plan to end homelessness. (Courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas)

"As this has evolved, we've seen strong development of the individuals leading [mission integration] departments. Now there's a master's degree in the field, and now it is better integrated into the organization and the process of decision-making. It's important we recognize the professionalism and importance of the role."

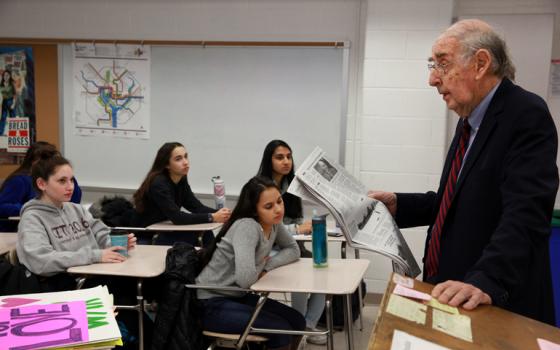

Brown first started at Mayo as a medical student in 1983 and has spent all of his career there, so not only is he director of the Values Council, but he has seen how the organization has lived those values for 36 years.

"It is still a very integral part of who we are and who we aspire to be," he said. "I've developed a really strong understanding of how the Franciscan sisters helped to inform the institution that we are, with these Mayo-Franciscan values that we hold so dear. These values inform the decisions we make."

For example, when Mayo wanted to add proton beam therapy to its options for cancer treatment, the cost was originally estimated at $100 million, which grew to $368 million to build proton therapy centers in both Minnesota and Arizona. Proton beam therapy is similar to radiation therapy for tumors but is more precise, allowing doctors to use a higher dose of radiation on the cancer cells while doing less damage to surrounding tissues than radiation therapy.

As explained in Ken Burns' documentary "The Mayo Clinic," the patient's cost of the therapy would normally be based on the overall price tag of the equipment, which would have put proton therapy out of reach of most patients and outside most health insurance coverage. But Mayo-Franciscan values don't align with limiting the best available treatment only to those patients who can afford it, so at Mayo, it costs the same as traditional radiation therapy, the documentary says.

Having the sisters' mission as the foundation for every decision means much more than just hanging a crucifix in the hospital, said Mercy Sr. Helen Amos, executive chair of the board for Mercy Health Services in Baltimore, a sponsored ministry of the Sisters of Mercy.

"I get this all the time. People talk about how they walk in here, and they feel a difference," Amos said.

Amos and two others are the only sisters employed there, and Amos is one of four sisters on the 30-member board. But the mission still permeates the culture, despite the lack of sisters in day-to-day operations, she said.

"We have the luxury of being driven by a set of values that flow from a religious tradition," Amos said. "We're not performing for the sake of our shareholders. We're performing for the sake of perpetuating a mission.

People talk about how they walk in here, and they feel a difference."

—Sr. Helen Amos

That philosophy of mission versus shareholder value has sometimes made Catholic health an island in areas otherwise barren of health options, both in rural areas and central cities.

In rural areas, Catholic health care is often the only health care: CHA says more than 1 in 7 hospital patients in the United States are treated in a Catholic health facility. One study found that in 10 states, 30 percent of the acute-care beds were owned by a Catholic organization or affiliated with one, the New York Times reported. That has led to criticism that if a Catholic health care provider will not perform a procedure for religious reasons, there is no other option.

Keehan said critics should instead ask why no other providers are in the area.

"In many cases, we're there because it's not a market that's an attractive market" for other hospitals financially, she said. "It's not a market where people want to be."

Crowley said it can be a challenge to keep sisters' values at the heart of everything, especially when sisters are gone, but it can be done, and it can be part of the organization's DNA. Even today, people at Mayo love to quote a reflection on the partnership from Dr. W. Eugene Mayberry, CEO and chairman of Mayo's board of governors in the 1970s and '80s.

"We know who we are with the sisters," Mayberry said. "We don't know who we'd be without them."

[Dan Stockman is national correspondent for Global Sisters Report. His email address is [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter or on Facebook.]