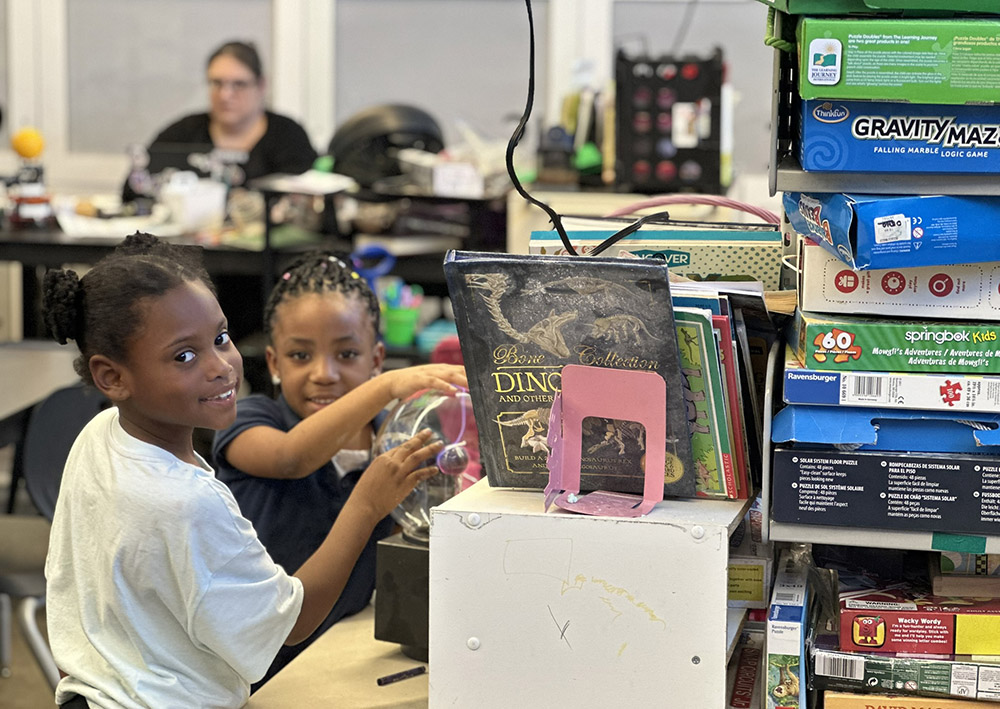

At Operation Breakthrough in Kansas City, Mo., girls ages 6-8 spend time in a room devoted to encouraging stem education after school hours. Activities range from legos to cooking to teach math and science skills. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

Berta Sailer and Corita Bussanmas — both Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary — had hoped to work themselves out of a job.

They weren't able to do that, but the nonprofit they started in 1971 in Kansas City, Missouri, is still going strong, even though Bussanmas died in 2021 and Sailer died in January 2024 and both had retired years before. In some ways, the institution known as Operation Breakthrough is stronger than ever.

"We know they're not gone," said Jennifer Heinemann, Operation Breakthrough's director of stewardship and planned giving. "They live on through those people who are there every day."

Bussanmas and Sailer started the agency because the working poor in the central part of Kansas City needed quality day care. Sr. Elizabeth Seaman, also a Sister of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, said Sailer named it Operation Breakthrough because they wanted to break through poverty.

A portrait of Srs. Corita Bussanmas and Berta Sailer hangs next to the Operation Breakthrough food pantry. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

Heinemann said 1 in 5 children they serve is unhoused at any given time, and that by their fifth birthday, almost two of every three have witnessed a serious act of violence. Many of them have seen multiple violent incidents.

"What would raise the hair on the back of your neck in your neighborhood is routine for our kids," she said.

But children are not just numbers.

"Statistics do not reflect the children we meet on a daily basis," Heinemann said. "Whether they're housed or not, have seen violence or not, they come in excited to be here. They eat breakfast, they're ready to learn — no one sits around and says, 'Poor me.' That's the hope for me — that they can go through all this and still make it."

Seaman, who worked at Operation Breakthrough from the 1990s until 2014, said Bussanmas and Sailer initially started a day care in the convent before finding a building to rent for a dollar. Eventually, they moved to a building on Troost Avenue, historically Kansas City's racial dividing line.

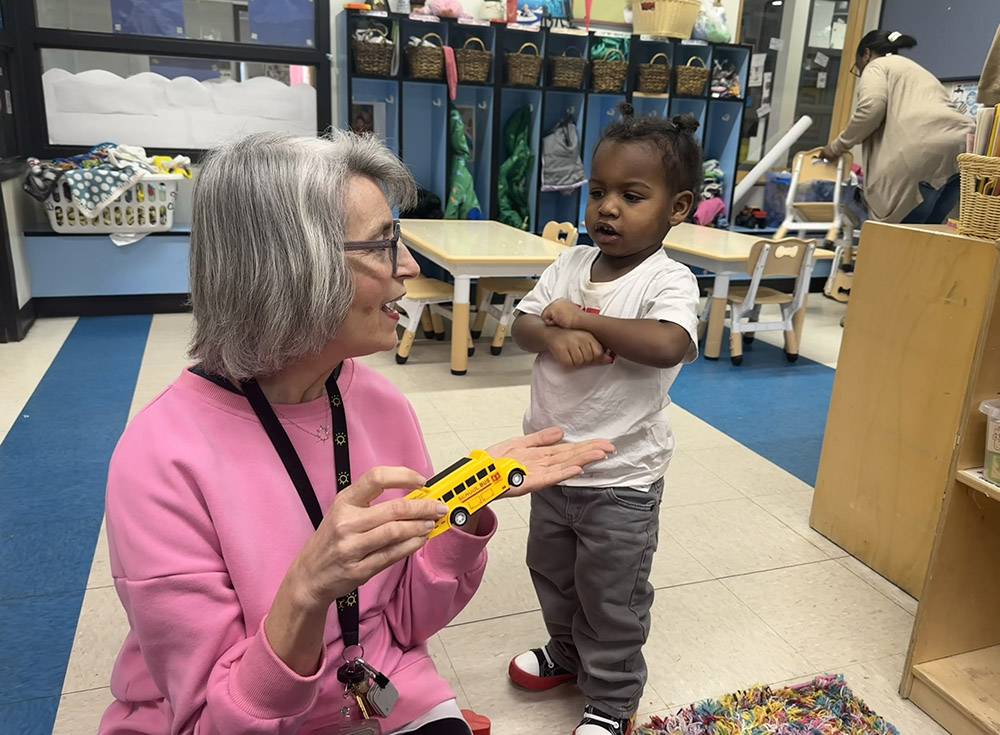

One in five kids at Operation Breakthrough is a homeless child at any given time. "Who is homeless today is not the same as who will be homeless later,” Heineman said. "As much as we can, we make what happens here be the same," such as the caretakers who can devote time to truly bond with their students. "Sometimes it’s more important to bond with parents in order to move the needle with children; they need to trust us," she said, so that they can share relevant information in their life, such as having been evicted or having lost their job. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

"Saying no to Sister Berta was like waving a red flag in front of a bull. You did not say no to her," Seaman told Global Sisters Report. But she also had a way of making people say yes. "She was able to charm anybody."

Today, the little day care has grown into a huge operation, serving more than 700 children each weekday with programs ranging from day care for babies 6 weeks old to welding classes for high-school students.

It also has some high-profile donors: Travis Kelce, a tight end for the NFL's Kansas City Chiefs, has worked with Operation Breakthrough for years, with his foundation purchasing a building so Operation Breakthrough could expand its programming. Kelce's girlfriend, pop singer Taylor Swift, donated $250,000 in December.

Kelce said in a Chiefs podcast in November that he started out reading Dr. Seuss books to children there, and soon he was partnering with the agency.

"It was beautiful to see what that organization was doing for those kids," Kelce said.

A 6- and 7-year old spend afterschool hours in the Science Room engaging in hands-on experiments. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

But when he found out their programs stopped at eighth grade, he wanted to change that, so his foundation helped set up Ignition Lab, which serves 400 students aged 14 to 18 with programs in graphic design, robotics, green technology, computers, manufacturing, product design, automotive engineering, culinary arts and more. Recently, the students restored a 1969 Chevrolet Chevelle SS muscle car and converted it from a gasoline engine to an all-electric vehicle.

"A lot of those kids that I was reading to in preschool are now in the Ignition Lab, and they're doing great things with their lives," Kelce told the podcast. "It's just cool to see it all manifest and all come to life."

Heinemann said there are multiple success stories that stand out — like program graduate Chris Goode, whose company Ruby Jean's Juicery has juices in stores across the country, or the woman who builds affordable housing, or the third-year medical school student.

But there are multitudes of small successes that are just as important, like the girl whose mother and grandmother each had their first babies while in middle school, but she did not. She went to college, has a steady job, owns a home and is raising two honor students.

Extracurriculars at Operation Breakthrough include woodshop, welding, making furniture, computer programming, and cooking, among several others. To prevent some of the elaborate labs from being empty, Operation Breakthrough picks up students from nearby schools to hold their classes in these same labs, augmenting the curriculum in their schools. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

Charitable organizations often flounder once their founders are gone. But Sailer and Bussanmas were so committed to the cause, that hasn't happened.

"The mission is so powerful and we see it every day in the building, so it's easy to stay true," said President and CEO Mary Esselman. "It was their persistence, their resilience."

Heinemann, who has worked at Operation Breakthrough for more than 30 years, said it helps that Esselman seems to channel the spirit of Sailer. "Mary Esselman has Berta Sailer in her body somewhere," she said. "I don't know how this happened, but they are eerily alike."

Sailer and Bussanmas were so dedicated they became foster parents to more than 70 children over the years; at one point they had 11 children living with them.

"Sister Berta and Sister Corita, they literally took their work home with them — they took 11 children home after running Operation Breakthrough for 12 hours," Heinemann said. "Now I'm pretty much the age they were when they had 11 kids, and I think, 'How in heaven's name did they do that?' "

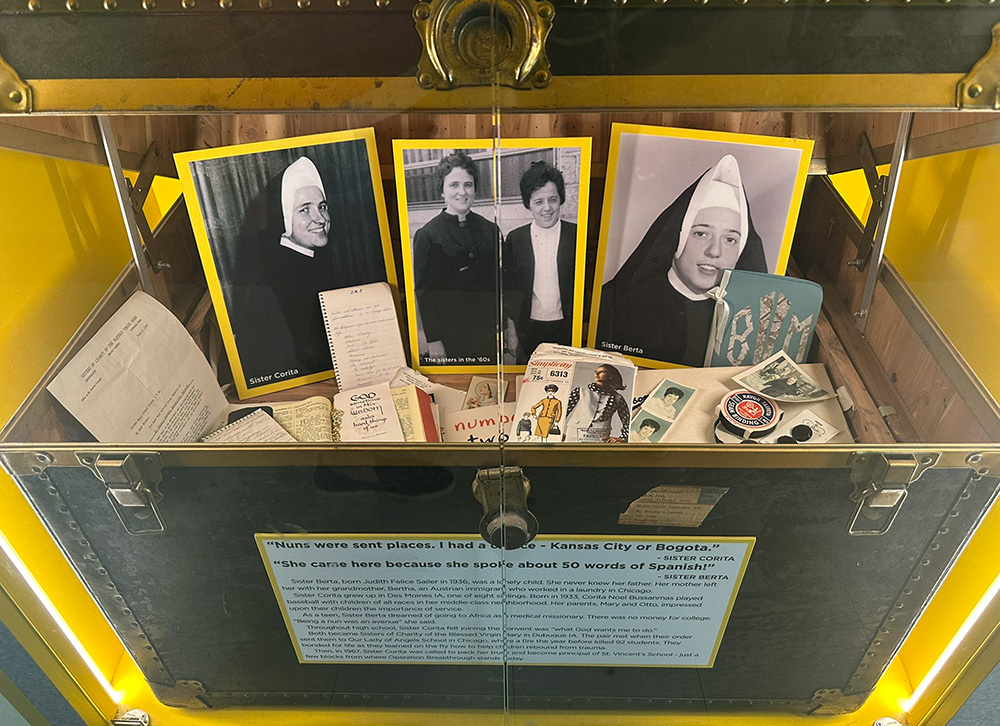

In the entrance of Operation Breakthrough, an exhibit displays the trunk with which Sr. Corita Bussanmas arrived in Kansas City before Sr. Berta Sailer joined her a year later. The two Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary founded the nonprofit in 1971. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

Seaman said that while Operation Breakthrough was focused on children, it helped their parents, as well.

"In the beginning, the people they hired were moms," she said, so the women got both quality day care and a job. As regulations began to be instituted, Operation Breakthrough helped the women get GED diplomas and get training to be certified as day care workers.

Heinemann said Sailer and Bussanmas were an amazing team: Sailer was the one who always said yes; Bussanmas was the one who kept her in check.

"Berta would plan all these great field trips for kids, and Corita would say, 'Is there any gas in the bus?' " she said. "Berta couldn't have been Berta without her."

Seaman agreed.

Advertisement

"Someone once said Berta worked and thought outside the box, and Corita tried to pull her back in," she said. "Berta said there's no rule or regulation that will stop her."

In fact, Heinemann said, Sailer seemed to appreciate children more than adults.

"Sister Berta used to say it's only the tall children that cause any problems — meaning us, the staff," she said. "You would think Operation Breakthrough would be a serious and sad place, because there are so many serious and sad issues to address, but it's joyful all the time."

And it was the sisters' ability to get people to say yes that made them unique, Heinemann said. She first met the sisters as a newspaper reporter, but ended up spending most of her career at Operation Breakthrough.

Jennifer Heinemann, Operation Breakthrough's director of stewardship and planned giving, reads to a toddler. The early education building is divided into "neighborhoods" — the purple neighborhood is for babies, green is for toddlers, etc. — and is organized by families so that all siblings fall under "green," for example, so moms interact with consistent staff. (GSR photo/Soli Salgado)

"It was 110% the sisters," Heinemann said. "It was not my intention to go out and find a nonprofit to spend all my waking hours in."

Seaman said that someone once broke into a warehouse where the sisters were storing toys they had been collecting for Christmas. So Sailer called the news media to spread the word that about $3,000 worth of toys had been stolen, and within minutes someone appeared with a $5,000 check.

When a woman had a stillborn baby and could not afford funeral arrangements, Sailer called a cemetery and made it happen, she said. When then-first lady Hillary Clinton visited, Sailer worked her magic on her, as well.

"Next thing you know, 20 of our kids are going to the White House at Easter," Seaman said. "She made that kind of impression."