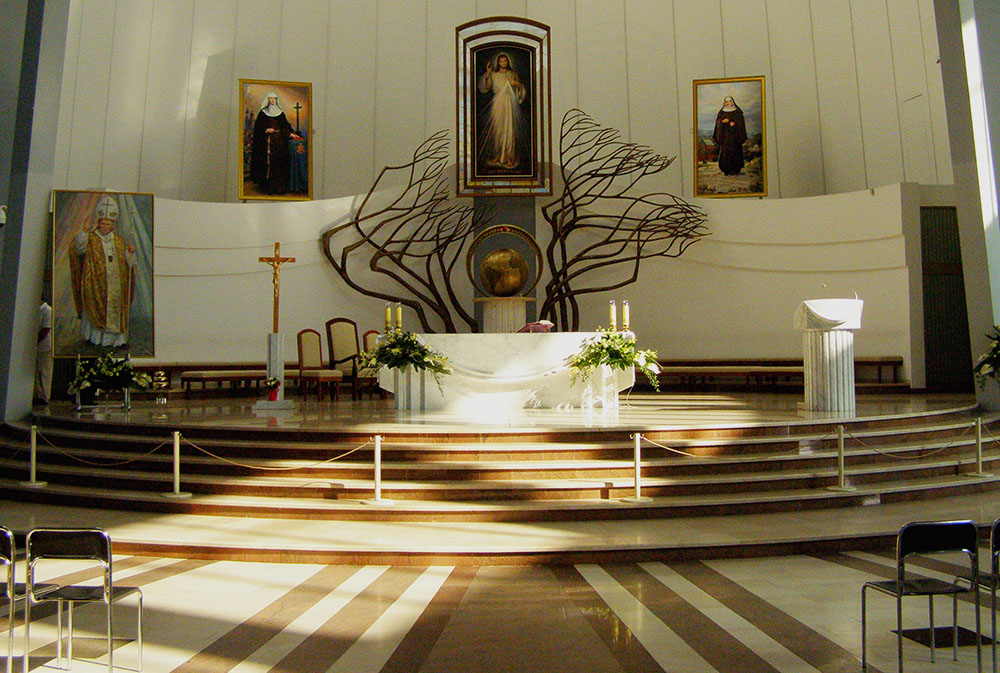

The altar in the Sanctuary of the Divine Mercy basilica in Lagiewniki, a suburb of Krakow, Poland (Wikimedia Commons/Albertus Teolog)

A vast white circular basilica stands amid undulating gardens, its 250-foot tower looming over a maze of terraces and walkways in Lagiewniki, a suburb of Krakow.

Since Pope John Paul II consecrated the church in 2002 and named it a basilica the following year, members of the Congregation of the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy have welcomed millions of visitors from around the world to the Divine Mercy Sanctuary, placing this among the world's top pilgrimage sites.

Lagiewniki's nearby older sanctuary contains the tomb of St. Faustina Kowalska (1905-38), whose mystical visions of Jesus earned her the title "apostle of Divine Mercy" and made the site a focus of worldwide attention.

The coronavirus pandemic has temporarily halted the large gatherings of visitors who thronged to the site, but it's also provided time to spur reflections throughout the church on how Poland's nuns can best continue their mission in Europe's most Catholic country.

'Each period requires us to find new ways of taking our apostolate to the world. If we're separated or closed off from people, this clearly poses a barrier.'

—Our Lady of Mercy Sr. Elzbieta Siepak

"We've a strong presence in the media and culture, and we're not complaining — as sisters, we feel fulfilled in realizing the tasks entrusted to us by Jesus," Sr. Elzbieta Siepak, the order's spokeswoman, explained to GSR.

"But each period requires us to find new ways of taking our apostolate to the world. If we're separated or closed off from people, this clearly poses a barrier."

COVID-19 has taken a relatively mild toll in Poland, with 1,694 deaths registered by the end of July. Although the country's female orders took urgent safety precautions, some suffered badly, with dozens contracting the virus in some convents, according to the Polish church's Catholic Information Agency, KAI.

Most kept the pandemic at bay and managed well without priests, according to Ursuline Mother Jolanta Olech, secretary-general of the Conference of Major Superiors of Female Religious Orders. Many followed canon law regulations that allowed their leaders to dispense pre-consecrated Communion hosts to members of their congregations, and they appreciated greater opportunity for "talks and exchanges."

Meanwhile, with Polish parish churches allowed to stay open throughout the pandemic, although to only small congregations, many sisters won praise for assisting local priests in maintaining health and safety requirements, as well as for staffing care homes, cooking for medical staff and providing support for needy citizens.

As in other countries, however, the coronavirus lockdown has led to some soul-searching — not least on how the Polish church might make fuller use of the huge asset provided by Catholic women religious.

Nuns wearing protective masks take part in a Corpus Christi procession in Krakow, Poland, June 11 during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Agencja Gazeta via Reuters/Jakub Porzycki)

"The fact is that religious sisters here are overwhelmingly associated with service roles, not with decision-making," explained Malgorzata Glabisz-Pniewska, a senior Catholic commentator and member of Polish Radio's Ethics Commission who has extensive contacts with Polish religious sisters.

"This support function was highlighted again when thousands of nuns came forward to help, but played no real role in managing the COVID crisis. Although they can and should be noticed a lot more, developing the position of women in the church here will need a change of mentalities."

Poland is currently home to 17,189 nuns and novices from 106 orders and congregations, with a further 1,952 ministering abroad, according to the Conference of the Major Superiors of Female Religious.

Founded in different historical periods, Poland's convents survived war and occupation, often sheltering fugitive Jews during the Holocaust. And while hundreds of priests were ensnared as secret police informers under communist rule, only a few dozen nuns were ever similarly entrapped.

Religious vocations peaked in Poland during the 1980s, inspired by the pontificate of St. John Paul II, but have since slowly declined, a trend broadly blamed on secularization. But female orders still play key roles in the country, running hundreds of schools, orphanages and care homes, as well as working in parish and diocesan offices, seminaries and Catholic colleges.

Advertisement

They're up-to-date technologically, with about half the country's 2,113 convents boasting their own websites, as well as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube accounts.

And while Poland's priests and bishops have been hit by persistent corruption and sexual abuse scandals, its religious sisters have been largely unaffected.

Meanwhile, education levels have risen, and most nuns now have degrees and diplomas, with 571 currently employed in higher education, over 4,000 as teachers and catechists, 1,522 as directors and treasurers, 1,272 as doctors and nurses, and at least a hundred as full-time media officers.

Average ages are also believed to be younger than in other European countries, giving Polish sisters special access to youth movements and mass culture.

Sr. Anastazja Pustelnik, from the Congregation of Daughters of Divine Charity, sold more than 4 million recipe books before retiring in 2016, while Sr. Anna Pudelko, a psychologist from the Family of St. Paul, is one of the country's top experts on women and fashion.

In 2018, Capuchin Sisters of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus took up boxing at a sports hall at Minsk Mazowiecki, to raise funds for their orphanage, and were shown on a viral YouTube video slugging it out in their habits to a hard rock theme.

The fighting nuns appeared on prime-time TV and politely declined training offers from Ewa Brodnicka, Poland's featherweight title-holder. But it was a sign of the imaginative, innovative thinking now emerging.

Nuns are also a feature of Poland's flourishing Christian rock scene.

Sr. Janina Kaczmarek, a singer-songwriter from the Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary, has a top-selling CD, "Take Care of Me," mixing country, R&B and bluegrass.

Sr. Julita Zawadzka, from the Holy Family Missionaries, was urged to pursue her singing talent after performing at a family music festival in the Tatra Mountains and is shown wandering through woods and cornfields in the video for her new CD, "Send the Wind." And Sr. Joanna Jablonska, from the Claretian Missionary order, stars with a rock band, Fragua, headed by a priest and fellow Claretian.

Claretian Missionary Sr. Jolanda Kafka, president of the International Union of Superiors General (Courtesy of UISG)

Last year, a Polish member of the Claretian Missionary Sisters, Jolanda Kafka, was elected president of the Rome-based International Union of Superiors General, representing 450,000 sisters from more than 100 countries.

"Religious sisters who've achieved prominence through their creative and professional talents have helped dispel stereotypes that nuns do nothing but pray — but they remain exceptions and there isn't much will for wider changes," Glabisz-Pniewska, the Catholic radio presenter, told GSR. "Although there's talk of handing more church tasks over to laypeople, it's assumed nuns shouldn't be in the public sphere. With every discussion focused solely on priests, religious sisters look set to remain in the church's shadows."

Are structures and attitudes due for an overhaul?

Though few Catholics in Poland would use such language, practical necessity may play its part.

Although around half of Poland's 38 million inhabitants claim to have followed online Masses during the coronavirus restrictions, according to a survey, church attendance is dipping as social and economic change erodes traditional Catholic practices, forcing religious communities to be inventive and take steps to conserve their position.

Olech, the 79-year-old secretary-general of the Conference of Major Superiors of Female Religious Orders, has been a forceful presence for many years, serving as superior-general of the Ursulines in 1995-2007 and a consultant to the Vatican's Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life.

In 2017, she warned Poland's Gazeta Wyborcza daily she would resist any infringement of the dignity of nuns, while in 2018 she insisted religious sisters should be better paid and acknowledged for their work alongside male clergy.

In February 2019, Olech confirmed that nuns were also being molested by male clergy, and said she hoped the new generation would demand support in tackling a scandal long "covered up in dark recesses of the human spirit."

"Certainly, this problem has a wider setting and reflects a general attitude to women in our society," Olech, a former sociologist and Vatican diplomat, told KAI at the time. "We're not children or people without free will — we can't allow ourselves to be used, but must respect ourselves and ensure respect from others."

Olech thinks the coronavirus has deepened tensions in the Polish church, threatening its mission and unity. But it has also raised questions about the church's "extensive structures" and placed a greater focus "on what's really essential, in simplicity and depth, without the crowds and the splendor."

"I have the impression this could become a time of experimentation," the veteran sister told KAI in June. "It could be a kind of workshop, as psychologists say, that helps develop new organizational structures and pastoral methods for the difficult times ahead."

Glabisz-Pniewska agrees.

Back in the '70s and '80s, Poland's nuns were viewed overwhelmingly as timid women who'd escaped from the world, she points out. Today, by contrast, they're likelier to be spirited and courageous — people who, far from fleeing, are bringing real capabilities and experiences into the church's service.

"All the endless wrangling here about church disputes and divisions have been centered on the church of priests and bishops, hardly involving religious sisters at all — and though nuns have opinions just as much as male clergy, they've had no platforms for expressing them," the radio presenter told GSR.

"The reformist demands being made in the Western church aren't likely to find much of an echo here — this is a different kind of country. But Poland's nuns would certainly like, from what I hear, to be better known and treated more seriously, and to have some influence on what happens in the church beyond their own communities."

Our Lady of Mercy Sr. Elzbieta Siepak with the Divine Mercy image of Jesus as St. Faustina Kowalska said he appeared to her in a vision in 1931 (Courtesy of the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy)

Back in Krakow's Lagiewniki suburb, the Divine Mercy sisters organized their first online "prayer formation" for the national assembly of followers of St. Faustina Kowalska at the end of June, to "strengthen the vocation of Divine Mercy apostles" and "deepen their spirituality and mission" in a post-coronavirus era.

The order, resident here since the 1890s, ran a home for single mothers and a 1,000-bed hospital for soldiers during World War I, and narrowly escaped having their convent commandeered as military barracks during Krakow's Nazi occupation. The congregation later survived communist repression with support from the city's Catholic archbishop, Karol Wojtyla.

Today, it runs online transmissions and an interactive website, two daily broadcasts on state TV and numerous other media ventures. In May, a dozen sisters even made a rap video, as part of a national appeal for health care professionals fighting COVID-19.

Siepak, the order's spokeswoman, dismisses talk of Polish nuns gaining positions of power and authority in the church and insists they enjoy a valued place in the country's religious life.

"We don't envy men for being able to hear confessions or stand before the altar, and we don't have aspirations to run the church — if we use our gifts fully, we'll lack nothing in proclaiming God's mercy," Siepak told GSR. "But we've never closed ourselves off from contemporary culture, and we're always looking for new ways and means to fulfil our mission. As new challenges appear, God sends us signs to read accordingly."

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]