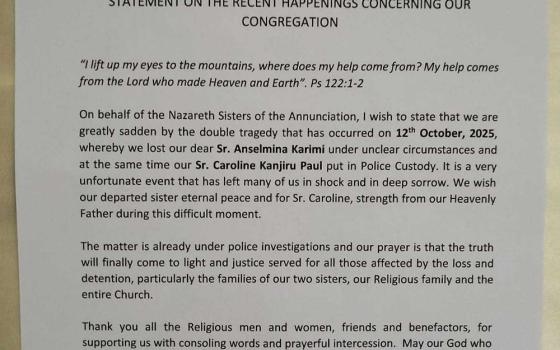

The heads of women's religious orders attend an audience with Pope Francis in Paul VI hall at the Vatican May 12, 2016. During a question-and-answer session with members of the International Union of Superiors General, the pope indicated his willingness to establish a commission to study whether women could serve as deacons. (CNS/Paul Haring)

(GSR graphic/Toni-Ann Ortiz; Art by Angelicon/Eri Fragiadaki)

Editor's note: This series, written by a member of the Pontifical Commission for the Study of the Diaconate of Women, addresses questions related to women religious and the ordained diaconate. This is the first of five essays — the next installment will be published Jan. 21. Join us Friday, Feb. 12, at 2 p.m. Central time, 3 p.m. Eastern, for "Witness & Grace: A Conversation with Phyllis Zagano and Sr. Colleen Gibson" focusing on highlights of this series. Click here to register.

In May 2016, Pope Francis responded to a question posed at the triennial assembly of the International Union of Superiors General (UISG): If women religious are already performing the many ministries of deacons, why not form a commission to study the restoration of women to the diaconate?

The pope responded immediately, naming 12 scholars the following August to the Commission for the Study of the Diaconate of Women who met in Rome four times and returned a report by June 2018. The pope gave a portion of the report to the UISG leadership at their May 2019 assembly. It has not been published.

Pope Francis gestures during an audience with the members of the International Union of Superiors General in Paul VI hall at the Vatican May 12, 2016. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Then, in October 2019, the same question arose, this time at the Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon Region. If nearly two-thirds of parish groupings are managed by women religious there, why not install women as lectors and acolytes, and share the synod's support of women deacons with the commission?

Again, Francis agreed, saying he would recall the commission, perhaps adding two or three new members. Then, in April 2020, he named an entirely new group to study the question. This second commission has not met, but is expected to begin its work sometime in 2021. It will be the fourth or fifth iteration of commission study of the same topic since the early 1970s. None recommended against women deacons.

Specific questions arise when considering women religious in the ordained diaconate. While in the Orthodox Churches, the question of women deacons is not debated — women, and especially monastic women, are and have been ordained as deacons — the Latin rite West has debated the issue for hundreds of years. The academic study is in addition to the four or five modern commissions that uniformly agreed that women deacons existed in the early church, East and West.

Some women deacons were religious, some were married, some were single, some were widows. But it was the UISG that brought the question directly to the pope. Even so, not all women religious seek ordination as deacons, and rightly so. The specific vocation to the ordained diaconate is not a replacement for religious life, nor is it a replacement for the priesthood. But, just as with the priesthood, the ordained diaconate can coexist with religious life.

While there is no guarantee that Francis will change canon law to allow women to be restored to this ordained ministry, this series of essays seeks to examine the questions most often raised by women religious about the possibility of women religious being ordained as deacons or of women deacons joining religious institutes and orders.

Why women religious as deacons?

Why did the UISG ask for a study of women deacons? Women religious are not women deacons, but many women religious undertake the tasks and duties of the diaconate. The UISG sisters pointed this out quite clearly to Francis when they asked for the study (and by implication his consideration) of women deacons in 2016, and their comments were seconded by the synod for the Amazon in 2019.

Members, observers and experts at the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon meet in a small working group Oct. 10, 2019, in the Vatican synod hall. Some of the groups proposed the ordination of some married men to the priesthood and the development of official ministries for women in the church, possibly including the diaconate. (CNS/Vatican Media)

If we look into history, we can locate specific times and cultures in which religious institutes formed to meet the pressing (and clearly diaconal) needs of the people of God. Why? During Middle Ages, the diaconate became increasingly ceremonial as the priestly class took over the administration of the church's treasure. Ministry to the people gradually but increasingly became centered in sacrament and ceremony. The diaconate faded and, excepting as a ceremonial office, virtually disappeared by the 12th century.

The Council of Trent (1543-63) unsuccessfully attempted to restore the diaconate as a permanent ministerial vocation. Throughout the ensuing centuries, the absence of a functioning diaconate contributed to the development of apostolic religious life to meet the needs of the poor and disenfranchised.

The exponential growth of religious orders and institutes over the centuries between Trent and the Second Vatican Council demonstrates the ongoing needs of the people of God. Women's apostolic institutes especially were formed to meet specific needs at specific times in specific territories, although many expanded beyond their founding locations to take up works far afield.

Advertisement

However, as apostolic institutes developed and grew, they were largely distinct from the diocesan structure, and especially separate from diocesan finances. In fact, apostolic religious institutes (both papal and diocesan) are primarily self-funded.

Those orders and institutes of men that include clerics find opportunities for their members' employment within diocesan structures, especially in parishes, in addition to their self-initiated works of education, social service and charitable endeavors.

However, apostolic institutes of women most often develop and run their ministries independently. While many women religious can and do find employment within diocesan entities, they are employees without any ministerial connection to, or faculties from, the bishop. They may work within diocesan structures, especially within school systems, but their pay in too many countries is often minimal and, unlike parish priests, they are not provided free room and board. Neither, whether as members of diocesan or papal institutes, are women guaranteed any form of support from the bishop.

Deacon Rick Fortune receives the Book of the Gospels at the Cathedral of St. Francis of Assisi in Metuchen, New Jersey, June 19, 2020, during a prayer service for racial harmony. (CNS/Courtesy of Metuchen Diocese/Gerald Wutkowski Jr.)

Canon law states that married deacons "who devote themselves completely to ecclesiastical ministry deserve remuneration by which they are able to provide for the support of themselves and their families" (Canon 281.3). The key words here are "completely to ecclesiastical ministry." Deacons who are part-time employees or volunteers in a given diocesan entity or parish are expected to maintain themselves and their families through their personal employment.

Different dioceses present different remuneration schedules for deacons, but many offer retreats and educational gatherings in addition to reimbursement for their ministerial expenses. In many dioceses, their "stole fees" received for witnessing marriages, performing baptisms and officiating at funerals are to be returned to the parish.

But women religious provide their own funds for their retreats and educational gatherings, as well as for their personal needs and the needs of their communities.

Beyond the question of remuneration, in asking for consideration of restoring women to the ordained diaconate UISG members recognized that clerical status carries with it the more formal connection to the sacramental and ministerial life of the church. Secular women ministers, pastoral associates, catechists and diocesan employees, including those of the various Orthodox Churches, have recognized the same. Hence, the calls for the restoration of women to the ordained diaconate have become increasingly urgent during the past 50 years or so.

Coincidentally, the past 50 years have seen a combination of local and universal synods discussing the question of women deacons, along with repeated iterations of papal commissions and of subcommissions of the International Theological Commission.

Therefore, the May 2016 UISG request for a commission to study women deacons must be viewed against the backdrop of the growing trajectory of formal and informal discussion informed by questions of justice for those ministering as well as for those ministered to. The discussion never centered directly on women religious, or on women religious becoming deacons, until the UISG membership brought up the notion to Francis.

Deacon Shainkiam Yampik Wananch leads a liturgy with indigenous Achuar people at a chapel in Wijint, a village in the Peruvian Amazon, Aug. 20, 2019. (CNS/Reuters/Maria Cervantes)

The most pressing question UISG presented is rooted in fact: Because women religious are performing so many diaconal tasks and duties, why can they not be ordained as deacons? Their logic is the same as that of the Diaconate Circles formed in Germany after World War II, which eventually became the impetus for restoring the diaconate as a permanent vocation for secular men, married or celibate.

In 1951, a group of young social workers joined to form the first Diaconate Circle in Freiburg, Germany. They published "Working Papers" from 1952 until 1966, by which time the Second Vatican Council was seriously considering restoring the diaconate as a permanent vocation.

During the intervening years, other Diaconate Circles grew in Germany, France, Austria and in Latin America, which joined together to form the International Diaconate Circle, based in Freiburg. In 1962, they petitioned the bishops of Vatican II, asking that the diaconate be restored as a permanent vocation.

When the question of restoring the diaconate as a permanent vocation arose, some council members voiced objections similar to those now voiced against restoring women to the diaconate. Two cardinals, Cologne Archbishop Josef Frings (1887-1978) and French Cardinal André-Damien-Ferdinand Jullien (1882-1964), then dean emeritus of the Roman Rota, the church's "supreme court," expressed concern as to how the restoration would affect the lay apostolate. As with the question of women in the diaconate today, the point that many diaconal functions were then performed by laypersons was advanced as a reason not to ordain men to the permanent vocation of deacon.

Yet then, as now, the fact that many laypersons are performing diaconal ministry is reason enough to identify more people — male and female — who may have vocations to the order of deacon. As Vatican II noted, these ministers would be strengthened by the grace and charism of diaconal ordination, a point that had been stressed by Cardinal Leo Joseph Suenens (1904-96), then archbishop of Mechlen-Brussels, and which remains as part of the continuing discussion.