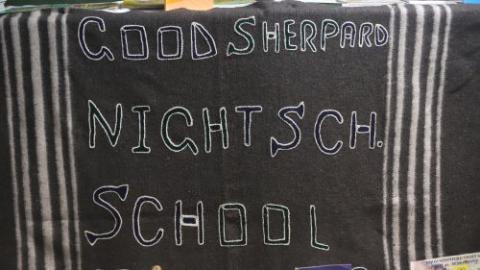

Sr. Amelia Dikiso, a member of the Good Shepherd Sisters of Quebec, teaches a herd boy how to put letters together to form words at the Good Shepherd Night School in Semonkong, a small highland town about 115 kilometers southeast of Maseru, Lesotho's capital. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

It's 8:30 on a Thursday evening, and dozens of herd boys are crammed into a classroom, elbowing each other and competing to look at battered old English and math books.

Seventeen-year-old Thabo Kobo is among them. He attends lessons every weeknight at the Good Shepherd Night School run by the Good Shepherd Sisters of Quebec in this tiny mountainous village in central Lesotho, where sisters offer Thabo and other herd boys like him an education.

Thabo dropped out of school in grade 3 at age 12 after his parents told him to look for a job as a herd boy to help them take care of the family and educate his sisters. However, after becoming a herd boy in a nearby village, he enrolled at the sisters' night school to continue his education.

"I wanted to continue studying, but my parents couldn't allow me. They only wanted my sisters to go to school," he said, noting that the move didn't dampen his dreams and he was now in grade five at the sisters-run school. "After getting a job, I decided to go back to school to achieve my dream of becoming an accountant one day."

He added: "During the day, I am always busy in the fields taking care of my employer's sheep, goats and cattle, but I attend classes at night when the animals are resting."

Boys who are herders attend a class at the Good Shepherd Night School in Semonkong, Lesotho, while maintaining social distance and wearing masks to protect themselves from COVID-19. The sisters started the school to cater to boys who have been culturally barred from accessing formal education but work as herd boys and shepherds. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

He is among thousands of boys in the southern African nation of over 2 million people who are being empowered through education by religious sisters. The sisters started the school in 2003 to cater to boys who have culturally been barred from accessing formal education but work as herd boys and shepherds.

Lesotho, a high-altitude, landlocked kingdom encircled by South Africa, is one of the few countries in the world where more girls go to school than boys. In many poor African countries, families choose to educate boys because of scarce resources and cultural practices that keep girls from receiving formal education, but here, the gender gap in education favors girls.

According to recent UNICEF data, Lesotho has 1.6 girls enrolled for every boy in secondary school, making it the highest ratio in the world for female education attainment. Other recent UNICEF reports show that about 22% of children between ages 5 and 17 are engaged in some form of child labor. More boys are involved in child labor than girls, the report says, which has led to the decline in school attendance for boys.

The Good Shepherd Sisters of Quebec run the Good Shepherd Night School for young boys who cannot go to school during the day because they work as herders to earn income for their families. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Sr. Jacintha Sefali, who is in charge of the Good Shepherd Night School, said the country's culture expects boys to protect and herd cattle, sheep and goats for their families or look for jobs as herdsmen, which requires them to drop out of school.

High unemployment and poverty in Lesotho have also led many teenage boys to withdraw from school to migrate to South Africa to work in mines or find other employment, she said.

"In our country, education for the boy child is the least of people's concerns," Sefali said. "No one bothers about the future of the boys. When a boy gets to 10 years old, the parents see him as old enough to earn money while girls are allowed to go to school."

Sefali said the trend has created hatred between siblings.

"The majority of the boys feel that only girls have been empowered and are treated better than them," she said.

At the school, the sisters teach the boys basic education using a normal school curriculum, including how to read and write, and provide meals to ensure the boys attend their lessons. At the end of every year, the boys are given exams. Those who pass are promoted to the next grade.

"For those too old to study or marry, we teach them hands-on skills on how to read and write, focusing on subjects such as mathematics and English to help them run businesses," she said, noting that thousands of boys have gone through the school since it started. "We have lessons every day, and we have committed ourselves to making sure that the boys are also empowered, just like the girls."

Sr. Jacintha Sefali of the Good Shepherd Sisters of Quebec poses for a photo with some of her students at the Good Shepherd Night School in Semonkong, Lesotho. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Nkieane Lillane is one of the beneficiaries. The sisters enrolled him at the institution in 2012, when he was in grade six, after his parents forced him to withdraw from school and look for a job as a herd boy.

Lillane, now 29, attended night lessons until he graduated after completing grade 12 in 2016.

"The sisters changed my life. They gave me money to start a small business after graduating," the father of two said. He now owns a tavern in Semonkong, a small highland town about 115 kilometers southeast of Maseru, Lesotho's capital. "The sisters are doing a good job. They have assisted very many herd boys in getting an education."

Other congregations in Lesotho also run night schools to empower boys. The Sisters of St. Joseph of St.-Hyacinthe run a night school on the mountain of Mokhotlong, a city in the northeastern part of Lesotho, where boys take animals in search of dwindling pasture.

Advertisement

The sisters also raise awareness of boys' rights among the communities and appeal to parents to empower them by providing an education.

"We are talking to parents and other stakeholders to ensure boys are not denied the right to education," said Sr. Anna Lereko, the provincial superior of the Sisters of St. Joseph of St.-Hyacinthe.

Thabo agreed with her, saying the government should prosecute parents who do not take their sons to school.

"The government and parents should give more opportunities to the boys just as they give to the girls," he said.