The stained-glass window depicting the seasons of life was designed by Sr. Nancy Raboin of the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ in Donaldson, Indiana. The tree-shaped linden wood crossbars of the window recall the linden trees under which Katharina Kasper, congregation foundress, prayed at a roadside chapel. In Germany, the linden tree is also a place to gather. (Courtesy of the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ in Donaldson, Indiana)

Funeral customs around the world have many common elements, but each culture and each religious congregation puts its unique stamp on the rituals around death and dying. For this month of saints and souls, panelists shared details of how they say goodbye to their sisters, as they responded to this question:

In your experience, what are some best practices around sisters' rituals for the dying, funerals and burial? How do these celebrations of their lives reflect the values of religious life?

______

Katy van Wyk, a Dominican Sister of St. Catharine of Siena of King William's Town, South Africa, lives in Johannesburg. After teaching, she served in leadership, later continuing in mission effectiveness for Dominican schools. Now, she conducts retreats, volunteers as a community art counselor with underprivileged children, and facilitates empowerment workshops for young women at risk of teenage pregnancy, substance abuse, and physical/sexual abuse.

When moving to a retirement home, our sisters are asked to write down details of their funeral and whether they want to be buried or cremated. I think there is an element of trust in this —sisters trust that their wishes will be respected — and they are.

Perhaps an unspoken question is: "Will there be someone at my death bed?" Again, there is trust. Someone will be there; seldom does a sister die alone in the hospital.

A burial outside Johannesburg, South Africa, for a family member of the author takes place in the Catholic section of a formerly segregated cemetery. Pall bearers include family and friends; after prayers and blessing over the grave, it is filled by men who have attended the funeral, while the mourners sing hymns. People stay until the grave is filled, and family members may then linger for good-byes. All are invited to the home or church hall for refreshments. For white people’s funerals, municipal workers fill the grave. (Chardonnay Loonat)

In our congregation, sisters take turns around the deathbed, singing the "Salve Regina" and a German hymn to Our Lady, "Segne du, Maria" ("Bless me, Mother Mary"). There is often good humor around the singing of the Salve. A sister may be on her last breath but "revives" during the singing of the Salve.

Once, I drove two elderly sisters to the hospital to visit another who was gravely ill. Unconscious and barely breathing, somehow, this sister was not ready to let go yet. John O'Donohue wrote:

"May someone who knows and loves

The complex village of your heart

Be there to echo you back to yourself ...

To carry you to the further shore."

Her friend, who knew her well — knew the "village of her heart" — walked her through the difficult and beautiful experiences they shared. I was struck by how the sick sister began to breathe more easily, the expression on her face becoming gentler and totally transformed. Then she just slipped away. It was a blessed and awesome experience.

In keeping with the values of religious life, our funerals are simple, with beautiful liturgies. Recently, our funerals have also become more private. In the past, our sisters were buried in our South African public cemeteries with one or several other funerals happening at the same time. Because of the age and frailty of survivors who cannot attend the burial or visit the grave later, cremation is becoming the better option. On the property of one of our retirement homes, a garden of remembrance has been established where the ashes of the deceased are interred.

Again, as John O'Donohue says: "I imagine that one of the great storehouses of blessing is the invisible neighborhood where the dead dwell." Whether burial or cremation, all is done with dignity. From that "invisible neighborhood," our sisters continue to bless us and to pray with and for us.

A cemetery in South Africa (Chardonnay Loonat)

Joetta Huelsmann is a member of the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ in Donaldson, Indiana. Early ministries included teaching, religious education and being a parish pastoral associate; later, she was co-director of a personal growth center, a staff member and spiritual director of a house of prayer, and the director of a retreat center. Now, she is serving as provincial councilor of her congregation and is responsible for associates, communications, the justice office and other community programs.

Joetta Huelsmann is a member of the Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ in Donaldson, Indiana. Early ministries included teaching, religious education and being a parish pastoral associate; later, she was co-director of a personal growth center, a staff member and spiritual director of a house of prayer, and the director of a retreat center. Now, she is serving as provincial councilor of her congregation and is responsible for associates, communications, the justice office and other community programs.

Believing in the resurrection (John 11:25), we Poor Handmaids of Jesus Christ fill out a "Resurrection Form" as a starting point for our funeral liturgy and wake service.

One of the considerations is: "What are some favorite themes or significant symbols in your life?" One for me is the turtle, which symbolizes the contemplative pace that is important for my life.

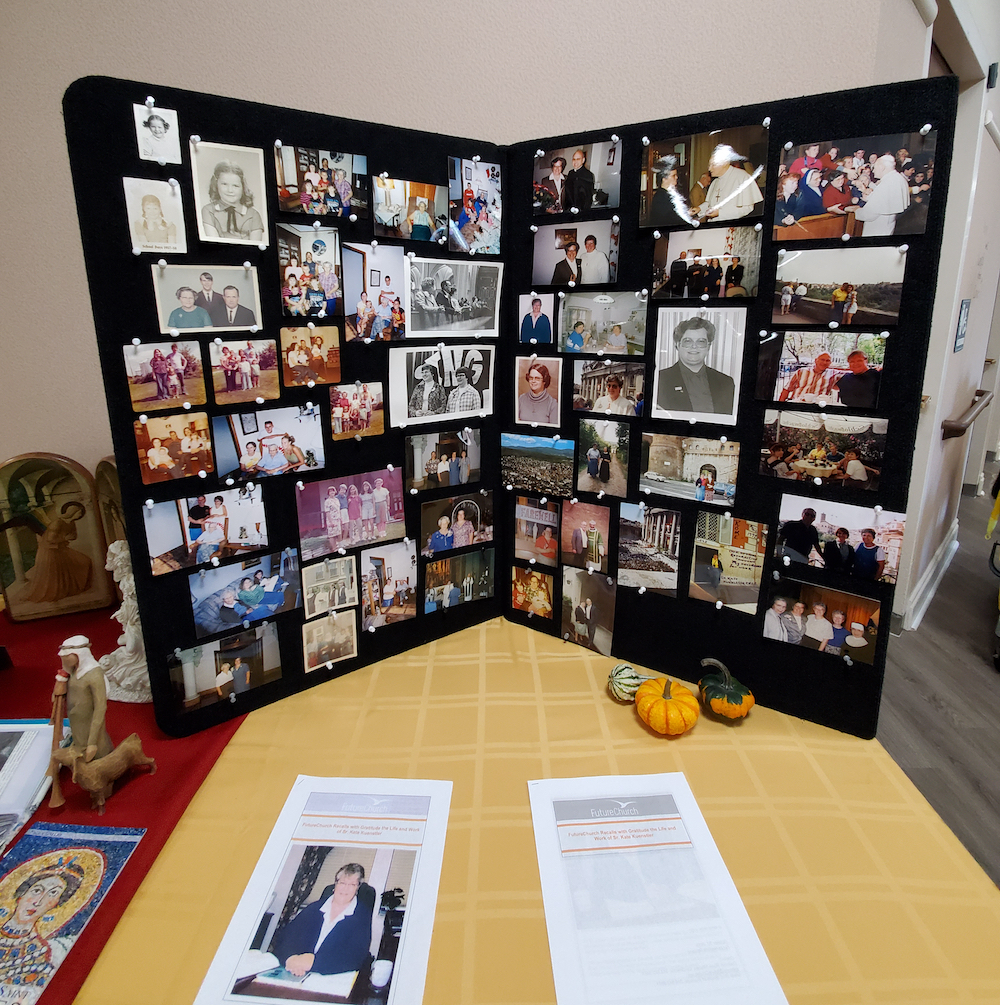

Photos and memories of Sr. Kate Kuenstler (Joetta Huelsmann)

On our forms, we list favorite Scripture passages, psalms and songs to be incorporated into our service. We suggest celebrants and a homilist as well as other significant people that we would like to have involved in the liturgy. We state a few highlights of our ministry and community life, as well.

A day before the funeral, the sister's body is brought to the chapel for viewing and welcomed by a short prayer service. At the viewing, individuals are invited to sprinkle the body with holy water. That evening, we hold a vespers service, designed with the sister's suggestions. At this service, someone shares a reflection about the significant highlights of the sister's life, after which others are invited to share their memories and stories.

The funeral booklet incorporates pictures of the sister throughout her life, and in the hallway, we have a table of pictures and other objects that were important to her.

The three display tables in the hallway outside the chapel, created for the funeral of Sr. Kate Kuenstler, are full of pictures and remembrances of Sister Kate. (Joetta Huelsmann)

At the end of the service, the coffin is brought to the hallway outside the chapel under a stained-glass window designed by our sister, Nancy Raboin. The window depicts the four seasons, which correspond to the seasons of our lives. The tree-shaped wooden crossbars of the window are made of linden wood, which has a significance in our history. St. Maria Katharina Kasper, our foundress, prayed and had many inspirations and visions at a roadside chapel surrounded by linden trees. In Germany, the linden tree is also a place to gather.

At the end of the funeral Mass, the closing hymn welcomes the sister into paradise. Incorporated within this hymn, we sing a litany of Poor Handmaid sisters who have gone before her — sisters who lived or ministered with her — and who will welcome her to heaven, as well.

At the end of the final blessing, we all sing "Glorious Title, Handmaid of Our Lord," composed by two of our sisters. From here, we proceed to the cemetery and again bless the casket with holy water as a final goodbye.

Jantana Wongsankakorn, an Ursuline Sister of Thailand, worked in the financial sector for 10 years. Inspired by the simplicity of religious life, she joined the congregation in Bangkok. After biblical studies in India, Mandarin courses in Taiwan and a tertianship in Rome, she ministered as a catechist and a member of the national chaplain team, then as a missionary in Cambodia. Now, she is a member of an Asian Pacific chaplain team and teaches mathematics at the Ursuline school in Bangkok.

Jantana Wongsankakorn, an Ursuline Sister of Thailand, worked in the financial sector for 10 years. Inspired by the simplicity of religious life, she joined the congregation in Bangkok. After biblical studies in India, Mandarin courses in Taiwan and a tertianship in Rome, she ministered as a catechist and a member of the national chaplain team, then as a missionary in Cambodia. Now, she is a member of an Asian Pacific chaplain team and teaches mathematics at the Ursuline school in Bangkok.

In Thai culture, a funeral is one of the most important events in a family. From visiting the dying person through the time of burial, a funeral shows the relationship between the living and the one who left the world.

Most of the population in Thailand is Buddhist. A Buddhist funeral consists of a bathing ceremony, daily chanting by a monk, and cremation. The Thai Catholic funeral is similar. A simple ritual is performed when the body is placed in the casket before being moved to the church. A wake usually involves three days of evening prayers, but it may last up to seven days, as the family wishes.

Our Ursuline sisters' wakes and funerals are very simple, with Mass, a homily and the presentation of "biography boards," with stories and pictures of the sister and her missions. Hundreds of students might come to the wake, especially for missionaries who served more than 50 years in Thailand. Even students who graduated years ago feel a big loss, for they have felt bonded with the sisters since their childhood.

Sr. Francis Xavier Bell's wake was a little unusual. Most of the visitors were surprised to find coffee and a variety of milk, yogurt and ice cream after the liturgy and eulogy. Why ice cream at a funeral?

After Sr. Francis Xavier Bell's wake liturgy, the sisters and guests feasted on Zonta ice cream and other milk products. Pictured are Sr. Kanya and Sr. Songsaeng. (Jantana Wongsankakorn)

Bell arrived in Thailand from Brooklyn, New York, in January 1953 to begin serving as a teacher in four Ursuline schools and in religious formation. In 1974, she went to the Ratchaburi Diocese (four hours away from Bangkok) to do social development, later moving to a remote village down a bad gravel road 17 kilometers from any town. The village was on a big piece of land surrounded by wild animals; the soil and water were not good enough for agriculture but were good for grass. To help the villagers develop a sustainable community, she changed the obstacle into an opportunity by developing a dairy farm.

Bell arrived in Thailand from Brooklyn, New York, in January 1953 to begin serving as a teacher in four Ursuline schools and in religious formation. In 1974, she went to the Ratchaburi Diocese (four hours away from Bangkok) to do social development, later moving to a remote village down a bad gravel road 17 kilometers from any town. The village was on a big piece of land surrounded by wild animals; the soil and water were not good enough for agriculture but were good for grass. To help the villagers develop a sustainable community, she changed the obstacle into an opportunity by developing a dairy farm.

Sister Francis asked for help from Zonta International, the Canadian Embassy and other benefactors to support the project, beginning with 26 dairy cows, which gave 30 liters of milk a day. After a year, they invested in machinery to produce pasteurized milk under the brand name "Zonta." Sister Francis worked there for more than 14 years, training and sending the staff to study abroad. The project continues as a well-known cooperative.

Sister Francis died in 2013. During the five days of visitation, the villagers provided Zonta dairy products every day to show their gratitude. "One taste (of Zonta ice cream) is worth a thousand words!"

Advertisement

Frances Hayes is a Presentation Sister living in Samson, Western Australia. With an academic background in education and history, she moved from primary education to religious education to administration in Australia and later became the English writer at the apostolic nunciature in Bangkok from 1995 to 2000. She then returned to Australia to minister as a support worker in aged care, a volunteer teaching assistant with refugee women and children, and a volunteer in an organization that builds connections with homeless and vulnerable people.

Frances Hayes is a Presentation Sister living in Samson, Western Australia. With an academic background in education and history, she moved from primary education to religious education to administration in Australia and later became the English writer at the apostolic nunciature in Bangkok from 1995 to 2000. She then returned to Australia to minister as a support worker in aged care, a volunteer teaching assistant with refugee women and children, and a volunteer in an organization that builds connections with homeless and vulnerable people.

My mother was extremely organized, so it was not surprising that she prepaid her funeral, having purchased two cemetery plots when my father died. I was asked to accompany her as she stipulated details: what type of service (no Mass, as most attendees don't go to Mass), no mourning cars (everyone has their own car), coffin type (nothing extravagant, as I am being cremated), lining material (nothing flashy, I'll be dead), simple floral tribute (flowers will die the next day). To her, it was matter-of-fact; to me, it was a little disconcerting.

Later, I realized how sensible it was, though I did quietly prepare a Mass (we decided to override her decision on that) with readings, hymns and roles for family members. When she died nine years later, our family was able to gather, share, reflect and grieve without the stress of organizing anything.

Recently, the leadership of my own Presentation congregation called for volunteers for a group to assist in the planning and celebration of special occasions, usually golden and diamond jubilees and significant birthdays, but added to these were funerals. Sisters were asked to submit suggestions for their own rituals: loved readings, favorite hymns, symbols, the celebrant and any other preferences. The sister is asked ahead of time about what clothes she wants to be dressed in, whether there will be a public viewing or not, will the coffin be of white or brown wood? Such discussions link death with life and the burial ritual with the baptismal ritual.

Understandably, each death and ritual is very different and personalized for the individual sister. The vigil prayers, Mass and burial are now a reflective experience as we are all focusing on the life of the individual. Comments are now: "I'm not surprised she wanted that reading, she has loved it since the novitiate," and, "I was with her when we first heard that hymn." The shared reflection includes a focus on how the particular sister has been a witness to the life of Jesus Christ and Nano Nagle, our foundress, and thus an aid to the spiritual journey of other congregation members.

For our Presentation congregation (average age above 80), these two practices — setting up our celebration group and individuals contributing to their own ritual — have resulted in greater openness, sharing, reflection and participation with death, seen as very much part of the ongoing journey of life in God.

Mary Ann Flannery is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati who has held teaching and administrative positions at several colleges. Before her community (Vincentian Sisters of Charity) merged with the Sisters of Charity, she served as community president and in other leadership roles. She has been a freelance journalist, the director of a Jesuit retreat house, and active in social justice issues for more than 30 years. She continues to offer retreats and spiritual direction.

Mary Ann Flannery is a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati who has held teaching and administrative positions at several colleges. Before her community (Vincentian Sisters of Charity) merged with the Sisters of Charity, she served as community president and in other leadership roles. She has been a freelance journalist, the director of a Jesuit retreat house, and active in social justice issues for more than 30 years. She continues to offer retreats and spiritual direction.

Evening shadows gather outside her window; the lights within dimmed with respect for the intimate moment — a soul about to transition.

Some of us keep customary vigil as her twin sister sits, head bowed in grief. We pray, and we wait.

This ritual is repeated whether one of our sisters dies in the infirmary, a hospital or a hospice. Sr. Jean Marian Crowley, whose ministry it is to handle the details in the process of a sister's dying and the ceremonies to follow, says, "We try to have the sister die here at the motherhouse, surrounded by family and those who know her. We can pray in her presence, and the familiarity often comforts her."

Preparations have already been made. The Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati are encouraged to provide information that will make final rituals meaningful and personal.

"Our practice is to make sure the sister has filled out forms following liturgical guidelines and including all of her designated wishes ... including the disposition of her remains," says Sister Jean Marian.

Sister Jean Marian has handled over 300 deaths and funerals in her nearly 20 years of this ministry.

"We try to make this a reflective, spiritual experience," she adds.

A traditional funeral celebration includes a wake service followed by a funeral Mass and burial of the body or cremains in the community cemetery. Some sisters choose a Mass without a viewing. If she has chosen to donate her remains to medical research — teaching even in death — she will have a memorial Mass sometime later. A recent teachable moment centered on a sister who had taught American World War II pilots how to use radar. The medical students stood there, awed at this sister's story and her contribution to history.

A memorial Mass is also offered for a sister who chooses a green burial. This requires that the sister be interred within 24 hours because she is not embalmed. She is "dressed" in a biodegradable hospital gown and wrapped in a biodegradable cloth, sometimes along with a favorite afghan, then taken to her final resting place. In the cemetery, the groundskeepers reverently remove the body from the hearse on a wooden pallet, and lower it into the grave. We pray the graveside prayers and sprinkle holy water on the remains of our sister.

The impact of this choice is powerful. Last winter, a sister-missionary to Latin America was lowered into her grave, totally free and still giving herself to the Earth she so lovingly served in the poor. A blending of a life and death in the cosmic Christ.

Yes, in death she was still teaching.