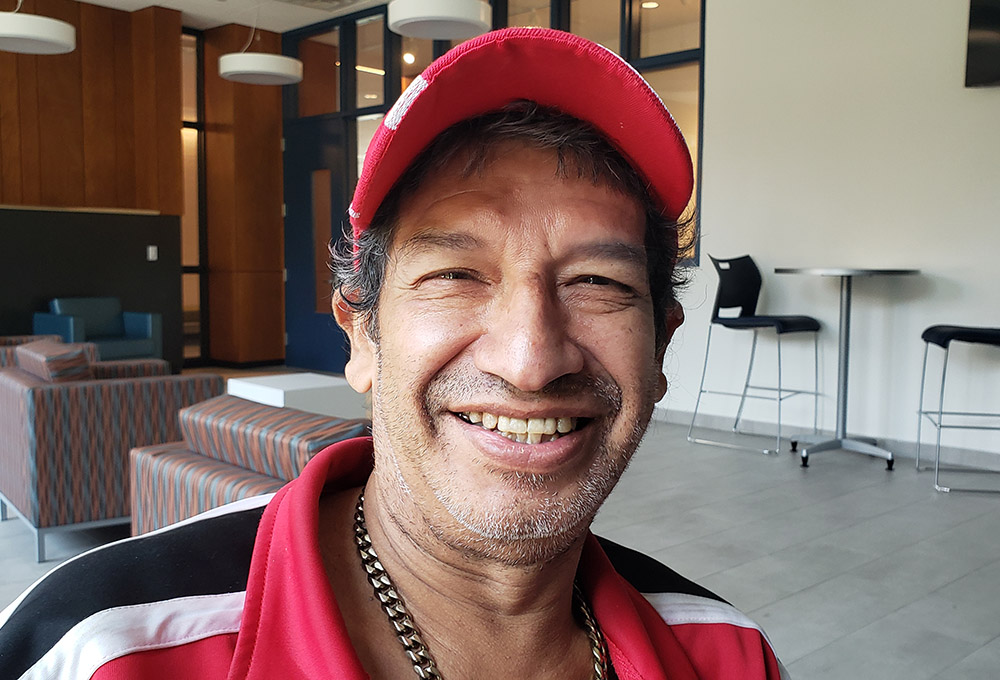

For 10 years, Carlos Bolanos was homeless, but in November, he became a resident of 3500 Park Avenue Apartments, a 115-unit residence in the South Bronx developed and run by the nonprofit The Bridge with money lent from the Leviticus Fund. "I live in peace now," said Bolanos, seen here in the building's social hall. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

For 10 years, Carlos Bolanos was homeless.

Those were not easy days. He slept on subway cars and got to know which train lines were safer than others.

"You had to sleep with one eye open and one eye closed," said Bolanos, an Ecuadoran-born New York City resident. "People don't know how dangerous it is, living in the street."

Life on the street and the drinking problem he developed after his father died in 2003 were taking a toll and worrying his family.

"I knew I wanted to change," Bolanos said.

Advertisement

In 2020, he found help at a Manhattan church with a homeless ministry and addressed his chemical addiction. He lived in a Manhattan shelter before arriving in November at a newly constructed 115-unit residence in the South Bronx known as 3500 Park Avenue Apartments, developed and run by the nonprofit The Bridge.

Bolanos, interviewed in July at the residence, said he still cannot believe his good fortune.

"I live in peace now," he said.

The Bridge was lent money by the Leviticus Fund, a community development lender created by a group of religious leaders that has cumulatively invested more than $142 million to improve thousands of lives in the New York City metropolitan area and in surrounding communities and states.

3500 Park Avenue Apartments in the South Bronx (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Sisters passionate about fighting poverty say the Leviticus Fund is tackling some of the same challenges and issues today it did at its inception in 1983: "the lack of affordable housing, day care, those kinds of things for the economically disadvantaged," said Mercy Sr. Rosemary Jeffries, current Leviticus Fund board president and now in her second term as a fund board member.

The cornerstone of Leviticus' work remains what it was at the fund's founding: assisting "projects that were going to help the economically poor but that found a hard time dealing with the bank to get a loan," Jeffries told Global Sisters Report.

"It's faith capital," said Greg Maher, executive director of the fund, which is based in Tarrytown, New York, and takes its name from the call for economic justice in the Book of Leviticus.

It also shows the strength of pulling together resources, Jeffries said. "We can do much more together than we can do alone."

'We can do much more together than we can do alone.'

—Mercy Sr. Rosemary Jeffries

As one of the nation's first community development financial institutions, or CDFIs (see sidebar), the fund has financed projects including housing, community health work, education and, more recently, access to food in communities with food deserts.

Leviticus' investment model is similar to purchasing certificates of deposit at a fixed interest rate for a specified amount of time. The investment, in turn, allows Leviticus to lend money to groups like The Bridge.

But now, Leviticus is further strengthening its work through a recently announced Legacy Fund — a pool of capital based on donations, not investments. Pooling their support into donations are seven original fund investors. Six are sister congregations: the Dominican Sisters of Sparkill, New York; Franciscan Sisters of Peace; Good Shepherd Sisters; Religious of the Sacred Heart of Mary; Sisters of St. Dominic of Blauvelt, New York; Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union.

Money from the Legacy Fund, permanently restricted for lending, will be lent and repaid to support future projects, said Colleen Ryan, Leviticus' resource development officer.

Mercy Sr. Rosemary Jeffries, a member of the Leviticus Fund board of directors (Courtesy of Leviticus Fund)

A donation, Jeffries said, can be used as permanent loan capital, expanding the capacity "to lend more money and probably take on some additional risk with some borrowers."

Leviticus also welcomes donations or investments by individuals. Individual investors, the fund said, may "invest in Leviticus by making a loan as small as $1,000 for a one year term that pays a fixed interest payment each year."

The fund's roots date to December 1981, when religious leaders in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut formed the Tri-State Coalition for Responsible Investment to address endemic problems like poverty.

That reflected something in the air at the time.

"There was a great effort in the '80s for congregations, especially women's congregations, to get involved directly for people in need. And I think that just continues," said Sr. Ellenrita Purcaro, Leviticus Fund board secretary and a member of the Sisters of St. Dominic of Blauvelt.

Sr. Ellenrita Purcaro, a Sister of St. Dominic of Blauvelt, New York, and Leviticus Fund board secretary (Courtesy of Leviticus Fund)

Founders of the tri-state coalition "saw that, if they pooled and invested their resources together, they could do more to reflect and advance the faith-driven values they shared: ensuring that the economically poor could live with dignity and self-determination; using their shared resources for the benefit of those with less; and protecting and sharing the earth's resources," says a history on the fund's website.

In May 1983, 27 religious congregations pooled $360,000 in capital to form what was first called the Leviticus 25:23 Alternative Fund. The fund has financed projects not only in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut but also Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Vermont.

In all, Leviticus has closed 359 loans since its founding, serving 192 borrowers, primarily nonprofit organizations, "but there are a few small businesses in the mix, as well as minority-owned businesses," said Maryann Sorese, Leviticus' communications and compliance officer.

The idea of the Legacy Fund "has taken off," Purcaro said. And it is doing so, Purcaro and Jeffries said, because the original members are committed to leaving a legacy for the future — a legacy "that we're so conscious about and want to preserve.".

In a May 22 statement announcing the creation of the Legacy Fund, Mercy Sr. Patricia Wolf, who was the fund's founding board president, said the founding congregations "took a risk on Leviticus, and now... nearly 40 years later, Leviticus is still here. Joining the Legacy Fund extends their membership in perpetuity."

Institutional values

Every project has its challenges, and The Bridge project in the Bronx was no exception.

Opened in November, the building is fully leased and provides rental housing for low-income families and seniors in addition to supportive housing for the chronically homeless, veterans with disabilities, and frail and disabled seniors.

"The need for supportive housing in New York City is enormous, so the project puts an important housing-related topic front and center," Sorese said.

In an interview at the Bronx facility's social room, Maher and Susan Wiviott, The Bridge's executive director, recalled that the project needed $3.2 million quickly because the owner of the property, a vacant lot, wanted to sell it immediately. Leviticus first heard of the need in February 2016, made a commitment to finance three months later and fully funded the project by August 2016.

"To get funding at that juncture was incredibly important," Wiviott said. "It was a lot of cash up front, and we needed it quickly."

Wiviott said the timing "worked out so incredibly well. We're here now, and it's a beautiful building, a safe and respectful place for its residents."

Maher said in this and other projects, Leviticus is committed to the idea "you matter and that you need to be treated with respect."

That speaks volumes of the importance of institutional values, which Maher and the sisters on the board say are hard-wired into the Leviticus Fund's mission and work.

Both Jeffries and Purcaro noted that the discussion at a recent board meeting was grounded in values.

"Just listening to these board members, bankers and lawyers and all of the people that are really financial wizards, far more than I — they were speaking mission, " Jeffries said. "They were really speaking mission."

During an online interview with GSR, Purcaro's face lit up as she recalled that meeting.

"Sitting with a businessperson who's making a recommendation to questions that were posed to us, he said, 'Well, financially, this might be the best way to go. But in light of what our mission is, this is what I would recommend.' And so, they have internalized it, and they're willing to buy into it and to see that it continues," Purcaro said.

Jeffries, Purcaro and a third sister, Dominican Sr. Peggy Scarano, serve on the 13-member board. The sisters and staff are aware that the aging of the sisters' congregations means a personal presence by sisters on the board may not continue indefinitely.

But none are bemoaning that, saying that the congregations' founding values will continue.

"Because people have been involved for so long, they really have absorbed and internalized these values. And so it's not, for me, a sad thing," Purcaro said. "I think it's hopeful that we know the good work will continue. And that's what's important for us, whether we do it or not.

"We have this phrase that we use [within our congregation]: 'You're doing it in our name because we can't do it ourselves.' "

Maher said he shares that sentiment, noting that at least one lay representative of a congregation sits on the board now.

"We expect the lay representative model to take over and to continue to be a vital voice of conscience guiding our work," Maher said.

The fund's bylaws specify that a quarter of the board's membership must be member investors — in this case, religious congregations or institutes, Maher added.

The values of the religious congregations "will continue to guide Leviticus' decision making" and "continue to be a vital voice of conscience guiding our work," he said.

In doing that, many benefit — like Carlos Bolanos.

"God changed my life," he said quietly during an interview last month. "Before, my life was centered on drinking. I don't need that kind of life anymore."

He likes his neighbors, socializing occasionally at building bingo games. "There are lovely people here. Very lovely."

But it is his own studio apartment that he cherishes most — a refuge where he can savor peace and quiet and even cook, a hard-earned joy. Spaghetti for breakfast is always welcome.

"I feel happy and blessed with a roof over my head, a place where I can relax and be responsible for my life and not drink anymore," he said, beaming.

His family is also relieved. At Thanksgiving dinner last year, one of Bolanos' nieces cried at the memory of worrying about him during previous holidays, wondering where he might be.

"They don't worry about Uncle Carlos being on the street anymore," he said. "They're happy that I'm happy."