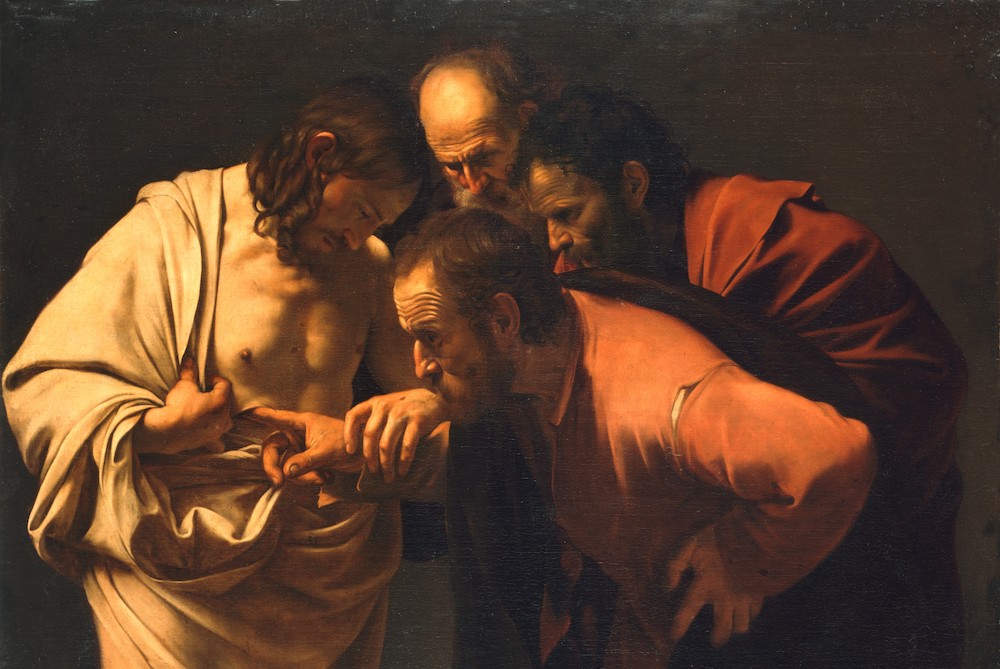

Detail of "The Incredulity of Saint Thomas" by Caravaggio, 1603 (Sanssouci Picture Gallery, Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin-Brandenburg collection)

We must feel

the pulse in the wound

to believe

that "with God

all things

are possible,"

taste

bread at Emmaus

that warm hands

broke and blessed.

—From "On Belief in the Physical Resurrection of Jesus" by Denise Levertov

This past Sunday, churches around the world heard the famous "doubting Thomas" story from the Gospel of John (John 20:24), one of the many wonderful Resurrection stories we hear during the Easter season. It's a familiar story, and the usual take-away is the same: We should believe in Christ's resurrection without needing to see proof of it.

A couple of years ago, Thomas' feast day (July 3) happened to take place during my annual retreat. This was the first time I'd made a retreat without a director or a program, so I let the Scriptures for the day be my guide. I spent this entire day reflecting on the Gospel for the feast, which was, of course, the doubting Thomas story. But I also spent the day reflecting on Caravaggio's masterpiece, "The Incredulity of St. Thomas," a painting I was familiar with but had never thought much about.

I reflected on how visceral this painting is — Thomas reaches out to stick his finger in the side wound of Jesus, his face filled with amazement. The contrast of shadow and light makes Jesus' side-wound the focal point of the painting.

I've talked to many other people about this work, and a common response is, "It gives me the creeps." Or, "It's kind of gross." Or, "It's upsetting."

The painting is upsetting; but so is the Resurrection. That God would take on imperfect flesh, which is weak, vulnerable, limited and oftentimes just gross, and then return after death in that same body — is upsetting. "The Incredulity of St. Thomas" confronts us with a deeply challenging aspect of the Resurrection: Christ's resurrected body is both glorified and wounded.

Which brings me to the other upsetting thing about the Thomas story: his proximity to Christ's wounds confronts us with our own wounded bodies. For me, this has involved confronting attitudes about my own body that have been less than positive.

There are so many messages in our society (and sometimes, unfortunately, in our church) that tell us to be ashamed of our bodies. This is especially true for women. I would bet there is not a single woman in this nation who has not struggled at times with body image, wishing aspects of themselves would look different.

I am no exception. As a teenager and young adult, my primary relationship with my body was wishing it was different. I was not (and still am not) a particularly athletic person: I was always the slowest girl in gym class when it came to running the mile, and I dreaded being chosen last for a game of basketball or kickball. Clothes shopping as a teenager was always stressful (and sometimes soul-destroying) because nothing ever fit or looked the way I hoped. Mirrors mocked the ways I fell short of an ideal that society upheld.

Advertisement

Reflecting on this story made me recognize the remnants of this body negativity that followed me into adulthood. I realized how little importance I gave to my body in my relationship with God, how I tended to approach my body as something that gets in the way of this relationship (for example, I can't tell you how often I've been frustrated by my propensity to fall asleep during prayer). I couldn't think of a single time that I felt grateful for having a body instead of feeling limited by it.

So it was a powerful change when my primary thought about my body became thank You for giving this to me rather than this is what I wish was different.

It might seem strange to feel gratitude for having a body. But if I didn't have a body, I could not taste good food, hug the people I love, watch a sunset or smell delicious things like bread baking and incense. I could not inhale the fragrance of chrism, feel the cool waters of baptism or taste the Eucharist.

Indeed, Jesus gave us the sacraments in recognition that we do have bodies, and we need to be able to encounter God in a sensual way. This is partly why Jesus invited Thomas not only to see his wounds, but also to touch them. The Gospel doesn't say whether Thomas touched Jesus or not, but Caravaggio decided to depict that touch. He even depicts Jesus holding onto Thomas' wrist, as if Christ took Thomas' hand to guide him to feel the wound in his side.

The lesson of the Thomas story is not just that we should believe in the Resurrection without needing to see or touch for ourselves. It's that Jesus invites us to see him and to touch him; he invites us to encounter his wounded and glorified body. And in that intimate interaction, Jesus can't help but encounter our own woundedness, reminding us that one day, despite our wounds and weakness, our bodies will be glorified like his own. Shouldn't that inspire gratitude for our bodies, too?