Dominican Sr. Jeanne Clark holds the photo she carried when she was charged with "obstructing a lawfully operated train" (Courtesy of Elizabeth Keihm)

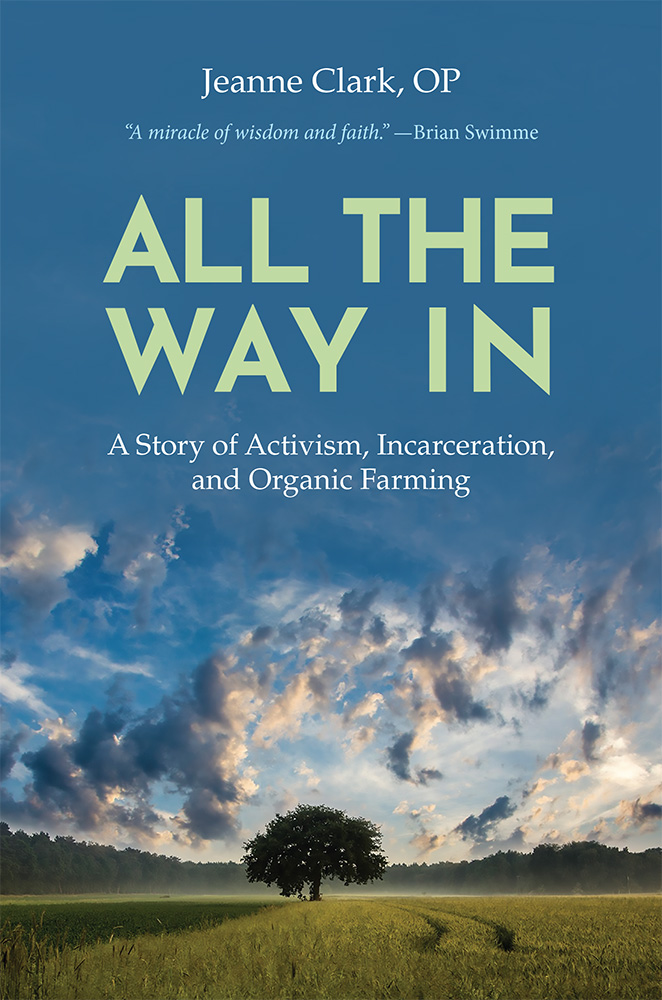

Sr. Jeanne Clark, a member of the Sisters of St. Dominic of Amityville, New York, has published her first book at the age of 85. All the Way In: A Story of Activism, Incarceration, and Organic Farming debuted in March, published by Orbis Books with editor Robert Ellsberg.

Clark is a peace activist whose protests at the Pentagon and nonviolent resistance to the Trident nuclear submarine sometimes led to jail time. She is the founder of Homecoming Farm and was a Pax Christi Long Island Peacemaker of the Year.

GSR: This book originated in 2019, when you attended a Thomas Berry conference at Georgetown University. Tell us more about that visit.

Clark: Anything to do with Thomas Berry, you can count on it that I'll be there. He has had such an influence on my life. But the hotels in Washington were very expensive, so I asked organizer Mary Evelyn Tucker [of the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, who had been Berry's student at Fordham] if she knew any place for me and Jayne Ann McPartlin [of the American Teilhard Association] to stay. She steered me to your home, which was newly in the process of becoming a faculty faith community.

There, I met Mary Evelyn's and your friend Megan Rice, and I saw a picture of the late Anne Montgomery on your bookcase. I said, "Oh, you know Anne Montgomery?" And you said, "I lived with RSCJ sisters who knew her at Anne Montgomery House." I also knew Anne. While I was resisting the Trident nuclear submarine in Bangor, Washington, Anne was resisting the Trident at its place of origin in Groton, Connecticut.

Advertisement

Tell us about your process of writing the book. You referred to it as "mutual spiritual direction."

You recorded a story I told the evening we met, and then we began a three-year-long journey together that resulted in the book. We would meet every week on Zoom, and you would ask me what was on my heart. I would remember and tell all the stories and share life with you, really. So we were journeying together, and that's a very unusual way to write a book, I'd say.

Then, about a year and half in, your colleague and friend Timothy Casey began joining us every week. [Casey is a Los-Angeles-based digital storyteller interested in Catholic sisters who has done work for the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, which is the primary funder of Global Sisters Report.] And I thought, "This is the way the universe is. Everything is in relationship to everything else."

And so to write a book in relationship with the lives of two other people was very special. Stories are meant to be heard and shared. In sharing the stories with you and Tim and hearing your responses, I was given the confidence to believe that my stories could become a book. I believe that our sharing together allowed the book to emerge.

What about your work with children?

I have a couple of chapters in my book relating to children and, most especially, those who come to be with us at the farm. I think that children are so close to the truth. They are very curious. When they're little, they're even very close to the ground, close to the soil, close to the puddles. Then we tell them, "Oh, don't go in the puddles." But they love splashing. We tell them, "Don't get dirty." They love getting dirty in the soil. They love to get their hands in there.

I sometimes think that we are born mystics, enveloped in the oneness of life. And then what we in our culture often do is educate the children out of that oneness with nature and into the culture of separation. Children talk to the trees and animals. They intuitively know that the trees and animals are subjects and not objects. But our consumer culture objectifies everything, even the children, and targets them at a very young age to become consumers. From the time they're very little, our culture allures them with guns. And why would a gun be a positive thing for a child?

There's a chapter in my book about two beautiful boys I love, James and John, and how James, from a very early age, became allured by weapons. He's a sensitive, beautiful child, not violent. He knows I don't like guns, and what I like is important to him. Children observe what we like, what we want, what we do. They observe everything. And he was very concerned that I didn't like guns, and he still is.

Dominican Sr. Jeanne Clark, leader of the group that started Homecoming Farm, on the grounds of the Dominican motherhouse in Amityville, New York (Courtesy of Meiling Sandy Ku)

Your father was a New York City police detective, and you write in the book about him reacting badly when you were arrested. Later, however, he changed his mind.

My friend told my father that I had been arrested at the Pentagon. And he said, "I think she's lost her mind." In a sense, he was right. I did lose one mind. I gained another one. He was very disturbed because he knew what the Washington, D.C., jail was like. When he pictured me there, it caused him a lot of pain.

Several events changed him. First, he learned that Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen had testified at my trial and was supportive of what I did. For my father, to see that an archbishop of the Catholic Church said that what I did was good really affected him. Also, he changed when he learned that I was arrested several times trying to stop the U.S. participation in a proxy war in El Salvador, holding the U.S. responsible for the deaths of the four churchwomen — Ita, Maura, Dorothy, and Jean — and of Archbishop Óscar Romero. They were killed, murdered, assassinated.

I brought my father to a film about Romero's life. I knew from that time on that he was very supportive of me. He was peaceful about what I was doing. These two bishops had changed his mind.

You said that a book by Jim Douglass inspired your title. What is your relationship with Jim and Shelley Douglass and the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action?

In 1978, I was at the Benedictine Monks' Weston Priory in Vermont and read Jim's book Resistance and Contemplation: The Way of Liberation. I was alone one morning in its small library yet had a very real experience of that book seemingly being put in my hand.

The question being asked in the book was, "And just how far would you like to go in?" It came, I believe, from one of Bob Dylan's albums, this story where the person answered, "Just far enough in to say that I’ve been there." And I thought, "For liberation, that's nowhere." You have to go all the way in. All the way into the truth. To go all the way in is to be liberated.

At the time I read that book and I heard that question, I was aware that the Trident submarine was being built and would soon be deployed on the West Coast. I went to my congregation and told them I felt this call to resist and to say no to the Trident submarine. And for anyone who doesn't know the Trident submarine, there's a meditation in my book, Jim Douglass' meditation on the Trident, which ends: "The Trident is the end of the world." And then the question comes: What do you do at the end of the world? The answer: You create a new one.

"You have to go all the way in. All the way into the truth. To go all the way in is to be liberated."

— Sr. Jeanne Clark

You also said that you were inspired by Sr. Miriam MacGillis, the co-founder of Genesis Farm.

Miriam has had a tremendous influence on my life because she introduced me to the teachings of Thomas Berry. I learned at Genesis Farm about food and farming. I came back to Long Island and founded Homecoming Farm at the motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Dominic.

At Homecoming Farm, the children learn that the bees, the ants, the earthworms, flowers and plants are part of the community. They learn that there are microbes we can't see in the soil. We can't see them with our naked eye, but they're the real farmers. They're very important in the process of creating food.

And so they learn what Thomas Berry taught. We experience it, that there's no such thing as the human community. There's only the Earth community, of which the human is a part. And if we could get that, if we could really understand that on that deep level, everything would change.

Editor's note: In the 2023 Catholic Media Association awards, All the Way In received first place in the memoir category and also received a Gold Nautilus Book Award in the spiritual memoir category.