The property of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Wheeling, West Virginia (Courtesy of Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

I first arrived at the motherhouse of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1966. I will never forget traveling up the lovely tree-lined hill for the first time. From the moment I set foot on that beautiful, unblemished land, I felt completely safe. That feeling is gone. Now, our land is being invaded and violated and polluted.

Because of a 2022 state law, our land can be fracked against our will if enough neighbors agree to fracking on their land. (Short for hydraulic fracturing, fracking is a process that fractures underground rock to extract gas and oil.) For decades, we refused the offers of gas companies to lease our land, but now it doesn't matter; our basic rights have been taken away. The fracking company, Expand Energy, wants to pay us, but it feels like an attempt to buy our silence.

We may not be able to stop the fracking — and the likely poisoning of our community's water and air that comes with it — but we can use our voices to prevent the worst outcomes from here. With the passing of Pope Francis, our great moral leader on faith and the environment, I feel even more compelled to use my voice. Extractive industries like fracking and mining can be divisive, but I pray we can witness each other's stories and concerns with grace and love. As for me, I have clashing emotions about recent presidential executive actions to boost fossil fuels and remove the guardrails on the industry.

I'm the daughter, granddaughter and sister of miners. Mining put food on our table in Fairmont, West Virginia, and that's pretty easy to understand. All the health consequences were not. Black lung and spinal arthritis disabled my father by his 50s. Black lung hit my brother-in-law, too.

Advertisement

Many years ago, there was little consideration about the health of workers and rarely did employers provide masks to protect against inhaling silica dust. Companies were primarily focused on mining coal. Later in life, I accompanied my father to court many times to secure help from the Black Lung Benefits Act. We never succeeded. When coal companies and the government saw how widespread black lung was among miners, I believe they did all they could to withhold benefits.

I fear fracking is also this way. Companies just want to extract the gas. They do not seem prepared to prevent, acknowledge or repair the damage to human health their extraction creates.

Fracking isn't harmless. Fracking drills into the ground and brings radioactive, toxic substances to the surface. About two dozen studies show just living around fracking increases heart disease, birth defects and cancer. I expect health problems will ramp up in West Virginia from increased extraction with decreased regulation.

These state and federal policies force us to surrender to the fossil fuel industry, endanger our health, and make all of us more vulnerable to pollution. We know pollution doesn't stay put. Toxins like soot pollution travel across the continent, penetrate our lungs and shorten our lives.

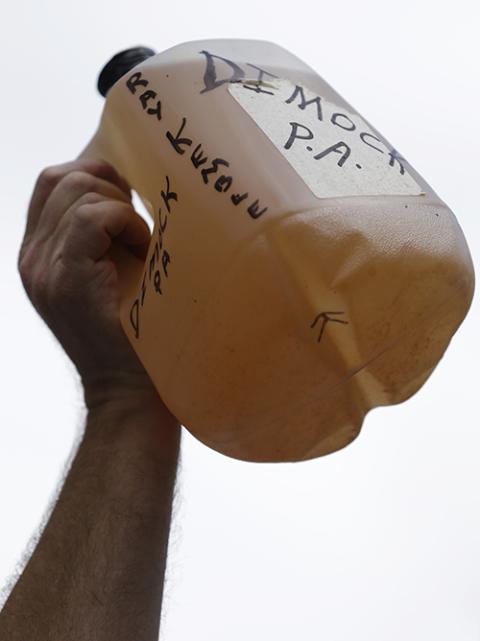

Ray Kemble of Dimock, Pa., protests fracking outside a Marcellus Shale industry conference as he holds a jug of what he said was contaminated well water, on Sept. 20, 2012, in Philadelphia. (AP/Matt Rourke, File)

When you can't even prevent fracking on your own land, protecting your health can feel hopeless. However, there are things we can and must do — like advocate for strong monitoring of water quality.

In another part of Appalachia, a fracking company pleaded no contest to crimes related to contaminating the drinking water of Dimock, Pennsylvania, with toxic metals and methane. The fracking company has to supply clean water to impacted residents for 75 years and fund the construction of a new public water system. I wish those people never drank that poisoned water, but at least they fought for a remedy and won.

When I became a religious sister, I thought my days of fighting industry to protect the people I love were behind me. At times, I feel very discouraged. I'm grieving the loss of our land, our health and our rights. Fracking companies are just here for profit, but this is our home. This is our land they defile and pollute. These are our neighbors who could get sick and die. Our love for each other and our care for this land are sacred. What they are doing to us may be legal, but it isn't moral.

The late Pope Francis understood the pain I feel. He wrote, "God has joined us so closely to the world around us that we can feel the desertification of the soil almost as a physical ailment, and the extinction of a species as a painful disfigurement." While Francis named the pain, he also gave us hope for its relief. He asked everyone to join a "pilgrimage of reconciliation with the world that is our home and to help make it more beautiful."

The St. Joseph Retreat Center on the property of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Wheeling, West Virginia (Courtesy of Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph)

It's natural to restore our deep instinctual connection to our earthly home and preserve it, as natural as breathing. But what stands in our way? Power and greed. Pope Leo XIV reminds us that the voice of the Lord calls us to act on environmental destruction despite these human forces: "That voice commits the Church to speak prophetically, even when it calls for the courage to oppose the destructive power of the princes of this world."

Being up against all that power and money can be discouraging sometimes, but we must remember: Hope is not an emotion; it is an action. Hope is choosing to believe that goodness is real, grace is just around the corner, and that we can make it so.

Here's how we are doing it. We Sisters of St. Joseph have decided we will accept the money that Expand Energy is paying landowners. We're not going to just leave the money to the energy companies to become even richer. But we will speak up. We will gather the community to stay informed and ensure accountability. We will fund projects to protect the people and the environment. We will bring that grace around the corner to our neighbors.

Just like it shaped my story and my family's story, fossil fuel extraction shaped all of Appalachia's story. We can't escape our history, but we can learn from it to shape a better future. God gave us minds to understand the problem, compassion to tend its harm, and voices to protect each other. Now it's time to use them.

A version of this op-ed was originally published by the Charleston Gazette-Mail and has been republished in the National Catholic Reporter with permission.