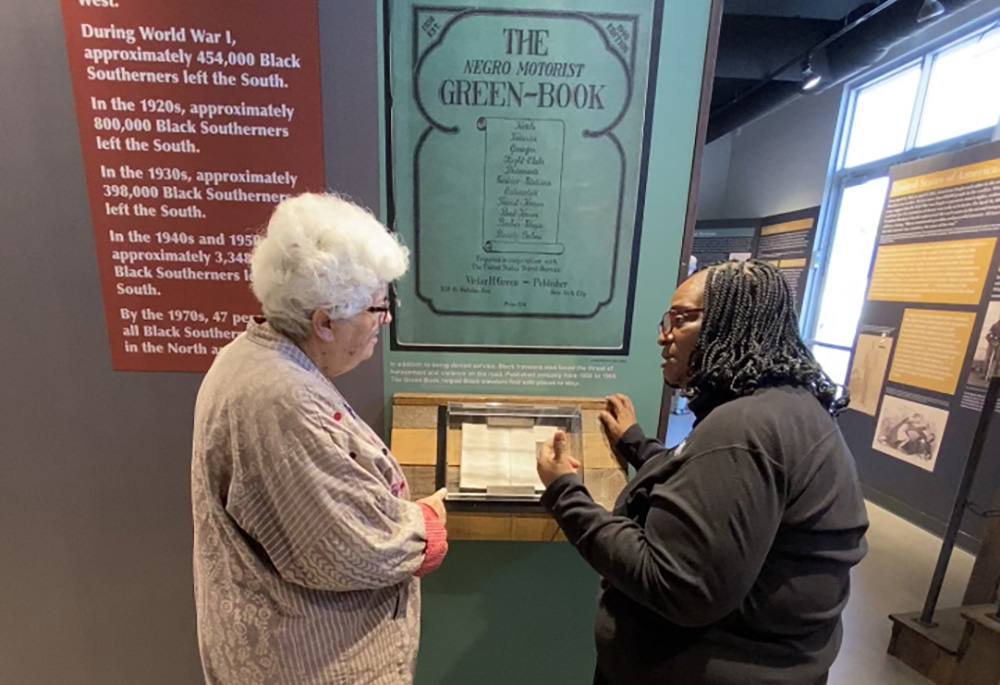

Sr. Barbara Pfarr (left), a School Sister of Notre Dame, visits America's Black Holocaust Museum in Milwaukee on Sept. 29. She listens to docent Brenda Jackson explain that in the 1930 edition of the Green Book, only two cities in Wisconsin, Fond du Lac and Oshkosh, offered services to the Black community. (Courtesy of Barbara Pfarr)

As I consider my experiences over the past 60 years, I recognize three examples of the spirit of white Christian nationalism.

As a teenager and an adult, I lived in "sundown towns," which did not allow people of color, especially Black Americans, to spend the night. This practice was found in Catholic small towns, especially in the Midwest. When I questioned others about the lack of people of color in our town, the answers were usually related to lack of employment opportunities for them. And little more was said.

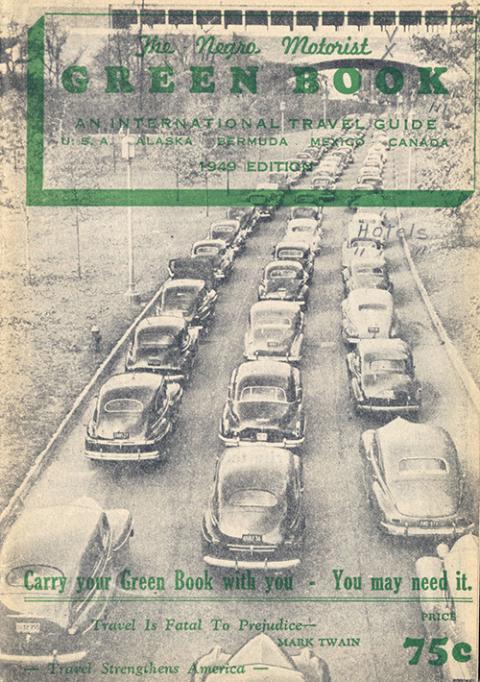

I often wondered how Black Americans knew how to travel and avoid such towns. Recently, I discovered the Black community found advice in traveling the U.S. through Victor Hugo Green's book titled The Negro Motorist Green Book, begun by a Black postal worker in 1936. It advertised Black-owned restaurants, motels and gas stations, as well as white businesses that welcomed Black travelers. He got the original idea from seeing such a book written for the Jewish community.

Several books and a movie on this experience of segregation are currently available, one of them being a children's book. As I read of the courage, planning and survival tactics that made travel for Black Americans possible, I am inspired.

Originals of the "Green Book" sold from 1936 to 1962 for 25 cents a copy. They were small enough to fit in a glove compartment. They alerted readers to the hazards of driving through white, Christian America.

Cover of the 1949 edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book (Wikimedia Commons/Seattle Public Library)

The author invited his readers to send him accounts of their recommendations for buying gas, overnight lodging, hairdressers, restaurants, funeral parlors and so much more. These services were added to the Green Book, where year after year it was enlarged.

Most of the suggestions were Black-owned businesses as well as any other businesses open to serving the Black community. In the early 1930s, only four towns in Wisconsin were included in the Green Book.

In the 1949 edition of the Green Book, Victor Green begins, "There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment."

Reflecting on this reality, I could not imagine the planning involved when a black person was searching for a home or a job, or visiting relatives.

They had to bring along enough food and gas to make the journey. Harassment was a constant threat, especially in the Jim Crow South. Lack of welcome in the North was an added anxiety, particularly in "sundown towns," which sometimes posted signs or rang a bell at 6 p.m. warning Black visitors to move on.

Sorry to say, I'm recognizing this injustice only now and see that it "takes a village" to continue this practice. I wonder if I would have the courage to ask what keeps this restrictive practice in place if I was living in a small "sundown town" today.

Another experience of white Christian nationalism happened in the 1970s, when I was asked to join another sister to visit a community member in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, whom we later found out was involved in a cult.

When we arrived, she greeted us by saying we had to wear a veil and long skirt, which we had to put on before we could be driven into the "colony." There, we had to join a discussion group.

I'll never forget sitting in a living room, listening to a tape recording of a speaker who was lecturing on the danger of "Martin Lucifer King"! After about 10 minutes, we said we needed to leave, which we did. After a restless night in a private home in the "colony," we spent three very long days participating in the group activities; we knew something was very strange.

At that time, I didn't know about white Christian nationalism, but now I recognize what this all-white community of well-educated white Catholics were discussing the principles of white nationalism.

Advertisement

Later, I learned that from 1974 to 2000, Hayden, a town 7 miles away, was the center of a strong neo-Nazi leadership group.

Writing this now, I realize that the basis of the group was blind obedience to a young priest, who was later ordained as "bishop." He was critical of Pope John XXIII and referred to him as "the antichrist." The spirit of fear marked many aspects of the group members' lives together.

After several attempts to help our sister return to the School Sisters of Notre Dame, our provincial encouraged her to leave the community, and both signed formal papers in which she left. Subsequently, the "bishop" married one of the young "sisters" from the colony and absconded with the money. His choice helped her choose to leave the cult and live independently.

A third moment of recognizing white Christian nationalism took place while I was a "Nun on the Bus" in 2015 with Social Service Sr. Simone Campbell. We were visiting various centers in Kansas, and after one presentation, we came out of the church and were met by a group of families. We learned they were from the Westboro Baptist Church based in Topeka, Kansas.

As they carried signs reading, "God hates f-gs," they were condemning us to hell for welcoming members of the gay community. Their children were also participating. The youngest seemed to be around 10, and their practiced screaming at us was unnerving. (Westboro is not affiliated with the Baptist church, and their practices have been publicly denounced by Baptist leadership.)

Suddenly, Sister Simone turned to us and said quietly, "I'm going to try to talk to them." She walked across the street.

As we nervously stood watching, they launched into more diatribe, and their shouting became even more frightening. After about five long minutes, she came back to us. Shortly after this, we got on the bus.

We could tell she was shaken by the experience. Then she said to us, "What could I have done differently?"

As we puzzled over what felt like a "no-win" situation, she responded to her own question. "Maybe I could have asked them to introduce their children, and that would've melted the ice."

However, since they wouldn't allow her to speak to them, we all agreed it was impossible to dialogue with them. Now I recognize this group as another example of white Christian nationalism and still remember how fearful we were at their viciousness.

For days, we visited several cities calling for a willingness to share ideas in a civilized manner, to listen to those who differ from us. However, at this exchange with the Westboro Baptist Church family, we had acknowledged not so much defeat but determination to continue building community wherever we are.

If the American dream is to survive, I want to be alert for signs of white Christian nationalism and try to name my feelings openly. This is my challenge as we move into another election year and try to foster acceptance of those who choose to live differently.