A 2017 photo shows life in a church-run compound near the Catholic cathedral for the city of Wau, South Sudan. The compound provided protection for residents of nearby communities fleeing from militia and paramilitary violence. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

If any place illustrates the hardship the coronavirus pandemic poses in a conflict zone, it might be Wau, South Sudan.

There, thousands of people had remained on grounds near the city's Catholic cathedral where they'd begun gathering for protection since 2016. Located on church-owned property, the compound had provided protection for residents of nearby communities fleeing from violence committed by militias and paramilitaries.

But local civil authorities, fearing the spread of COVID-19 in a confined area, told the residents in early April that it was no longer possible to sustain the compound and they had to leave and return to their homes. Authorities also cited the improved security situation around Wau, saying the fears prompting the original displacement had eased.

Church personnel, recognizing the health risks, supported the move, said Comboni Missionary Sr. Esperance Bamiriyo.

Though people had begun leaving the compound in 2019 because of better security in the surrounding region, there were still roughly about 7,000 persons remaining up until April, said Bamiriyo, citing a figure provided by a one-time camp manager.

Comboni Missionary Sr. Esperance Bamiriyo, director of the Catholic Health Training Institute, which trains young South Sudanese health professionals. (Provided photo)

"People got the message, but they were still skeptical," Bamiriyo, told GSR in an interview from Wau, a major regional city with a population estimated at 127,000 in northwestern South Sudan, about 400 miles northwest of the capital, Juba.

Though acts of outright resistance to leaving were small, fear was common. Those fears were confirmed initially when reports surfaced in April in local media of killings in areas where people had returned to the farms and homes they had fled. Among the reported victims were young farmers, both men and women, and women who were out collecting firewood, Bamiriyo said.

Though the killings have stopped for now, fear of flareups of violence are still realities, said Bamiriyo, a sister from the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, and director of the Catholic Health Training Institute in Wau, which trains young South Sudanese health professionals.

People take the fear of the virus's spread seriously, but returning to homes — many damaged or destroyed because of violence or neglect — has also put them in an untenable situation, Bamiriyo said.

" 'We are coming back home with nothing in hand,' " Bamiriyo said, reciting a common refrain of people who had been provided food on the compound by the World Food Program and others. "People are asking, 'How can I stay at home without a roof, without food?' " Complicating things: South Sudan's rainy season, which will make initial harvesting of land difficult.

"They are finding it a bit hard," Bamiriyo said. "People have no roofs."

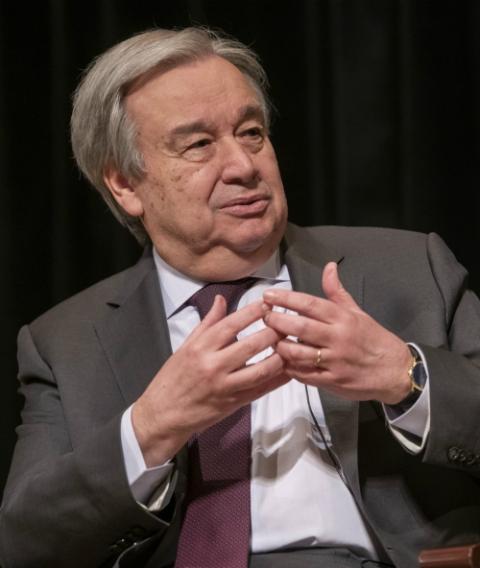

The difficulties are not surprising. In May, U.N. Secretary General António Guterres told the United Nations Security Council that the pandemic "is "amplifying and exploiting the fragilities of our world" and said that access to services for those living in conflict zones was being curtailed, UN News reported.

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres speaks Feb. 27 at the New School in New York City. (U.N. photo)

Guterres told the Security Council that his earlier suggestion, made in March, that warring factions in war-torn zones stop fighting was well-received but had "not been translated into concrete action," UN News reported. In calling for a cessation of fighting, the UN head said, "The fury of the virus illustrates the folly of war," adding, "it is time to put armed conflict on lockdown and focus together on the true fight of our lives."

But such a fight is particularly challenging in a country like South Sudan, which was already struggling with competing political and military factions trying to end a six-year civil war believed to have killed 400,000 and displaced more than 4 million. "The political situation is fragile," Bamiriyo said. "The peace process is fragile."

Since the outbreak of war, several peace agreements have collapsed, though hope for stability was revived last week when President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar, longtime political rivals, agreed to a plan for selecting governors of the country's 10 regional states.

But the challenges for South Sudan remain serious, such as the gaps in a national health care system that is not prepared for the "normal" persistent problems of malaria and yellow fever that become dire during the rainy season, Bamiriyo said.

"The health care system wasn't prepared for a big outbreak like this," Bamiriyo said. "The minimum basics are not there." The BBC reported June 16 that South Sudan has 1,693 confirmed cases of coronavirus, with 27 resulting deaths.

"They don't have physical infrastructure or institutional infrastructure," added Sr. Joan Mumaw, the president and chief administrative officer for Friends in Solidarity, the U.S.-based partner of Solidarity with South Sudan, a church-based ministry that supports the work of the Catholic Health Training Institute in Wau and other institutions trying to strengthen humanitarian and educational work in South Sudan.

"To have a pandemic on top of everything else is such a challenge," said Mumaw, a member of the Sisters, Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, or IHM Sisters.

Sr. Joan Mumaw, standing front, with Sr. Esperance Bamiriyo, principal of the Catholic Health Training Institute in Wau, South Sudan, and a Comboni Missionary Sister, right, with 2019 graduates of the institute. The graduates come from different tribes around South Sudan but respect and appreciate the different cultures on campus, Mumaw says. (Courtesy of Solidarity with South Sudan)

Anna Dombrovska (Provided photo)

Challenges in the Ukraine

Ukraine is facing similar challenges, said Anna Dombrovska, projects officer for the Catholic Near East Welfare Association, which supports the humanitarian work of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, an Eastern Catholic denomination in communion with the worldwide Catholic Church.

Available data as of June 15 show that the eastern European country, with a population of 42 million, has had 31,810 COVID cases, with 901 deaths and 14,253 people recovering from the disease, said Dombrovska.

But the data has gaps — it does not include the conflict areas of eastern Ukraine currently occupied by Russia. And an alarming statistic shows that the country's health care system has failed to protect its health care workers. Twenty percent of 5,537 doctors and nurses have been infected by COVID-19 and 40 have died, Dombrovska told GSR.

The response to COVID, she said, has been hampered by an insufficient supply of personal protective equipment and ventilators. Adding to the problem is inadequate testing capacity — the result of a country faced with a faltering economy and "burdened by the six-year war with Russia," Dombrovska said, as well as long-standing corruption and the continued legacy of totalitarian rule.

For many Ukrainians, the pandemic and the resulting lockdown proved to be a huge adversity.

"It was the end of the world for many of them," Dombrovska said in an interview, given already high rates of poverty. This was particularly the case in the east, which borders the occupied areas — places with high numbers of displaced persons from the Russian occupation and already marked by hardship and struggle.

Though the lockdown, which began March 12, is being eased in less-affected parts of the country, many quarantine measures — such as wearing masks in public places, working from home, banning of mass events — "are still in place," she said.

A priest prays while worshippers keep social distance during a ceremony to bless Easter cakes and eggs outside the church before a Ukrainian Catholic Easter liturgy in Lviv, Ukraine, April 18, during the COVID-19 pandemic. (CNS/Pavlo Palamarchuk, Reuters)

Sr. Annie Demerjian, a member of the congregation Sisters of Jesus and Mary (Provided photo)

In Syria, a health threat to a country at war

Syria is dealing with the pandemic in the midst of continued war and international sanctions — with more expected to come — that have brought the country's economy to its knees.

"We've lived through all kinds of bad conditions: lack of food, fuel, shelling," said Sr. Annie Demerjian, a member of the congregation Sisters of Jesus and Mary, interviewed by telephone from the Syrian capital of Damascus. It has been difficult to "worry about something else, because we have been through a lot, it's too much of a burden. Syria deserves peace."

A June 12 Associated Press report said the extent of the coronavirus' toll in Syria is not known. "Testing is lacking and authorities have reported only 152 cases and six deaths in government-controlled parts of the country," the AP reported.

Demerjian said she has heard a figure of 164 cases, and that 68 people have recovered, as of June 17. Whatever the numbers, Demerjian believes authorities handled a two-month lockdown wisely, but added that the overall situation remains dire. "People are so tired," she said.

The war-related humanitarian ministry Demerjian and others in her congregation have provided — such as food and cash assistance, as well as a microcredit program — continues, but in a more limited way because the lockdown has made reaching people difficult.

"The coronavirus has paralyzed life in the city," she said, adding that hunger is a reality for many, and that some have taken to social media to offer a kidney or an eye as a way to make money.

Paradoxically, during the worst of the war, from 2011 to about 2018, emergency assistance provided more food to people than now.

"More sanctions, coronavirus," Demerjian said. "It's like you're trying to kill these people, there is no life for them anymore. Is it right to do that?"

Such pleas are ultimately about the need for peace, with some still hoping that nations and warring factions will heed the call of U.N. Secretary General Guterres and "put armed conflict on lockdown."

A photo from 2017 shows life in a church-run compound near the cathedral in Wau, South Sudan. (Chris Herlinger)

But Sr. Esperance Bamiriyo in South Sudan is not convinced that the COVID pandemic will be the catalyst for peace.

"I don't think the warring factions consider COVID-19 as a way to stop fighting," she said. In fact, she added, "Some even wish that their opponents will pass on from it."

Still, she is hopeful that that country will ultimately turn a corner and that the spirit she sees among the health care students she knows in Wau will take further root in South Sudan. "We live in hope that the situation will improve."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is [email protected].]

Advertisement