Historian and author Bronagh McShane with Sister Bonaventure and Sister Colette of the Poor Clares Galway at the launch of McShane's book, "Irish Women in Religious Orders, 1530-1700: Suppression, Migration and Reintegration," in 2022 (Courtesy of the Poor Clares Galway)

Bronagh McShane is a historian and a fellow with the Royal Historical Society specializing in the history of women, religion and gender. Her new book, Irish Women in Religious Orders, 1530-1700: Suppression, Migration and Reintegration, is the first comprehensive study of the lives and experiences of Irish nuns in the two centuries after the Reformation. The book analyzes Irish nuns' experiences in Ireland and in Europe in that time period and explores the familial and patronage networks that facilitated Irish nuns' formation in exile and return to their homeland.

McShane completed her doctorate at the National University of Ireland Maynooth. She conducted research for the book in archives across Ireland, the United Kingdom and Europe, funded by the National University of Ireland through a research fellowship in humanities. She currently lectures in the Department of History at the University of Limerick.

The cover of "Irish Women in Religious Orders, 1530-1700: Suppression, Migration and Reintegration," published in October 2022

GSR: From your study of these Irish nuns, what impression did they leave on you?

McShane: My lasting impression is of the resilience and perseverance of the individual women whose stories I tell in the book.

They were constantly up against very challenging circumstances. Ireland during the late 16th and into the 17th centuries was going through a very turbulent phase. There were rebellions, uprisings, outright war and the Cromwellian conquest. Yet, throughout all of this, these women were upholding their way of life and doing everything they could to continue it.

Some of them began their formation by joining English convents in Europe. But they wanted to move back to Ireland to be able to propagate the message of Counter-Reformation Catholicism despite the extraordinarily challenging circumstances. Their movement to and from Ireland and Europe is a fascinating part of this history. They are pursuing an enclosed, cloistered way of life, but movement outside and beyond the convent is essential to being able to observe a monastic way of life. It is a contradiction, in a way.

Bronagh McShane sits in the cloister garden of the Convento de Nossa Senhora do Bom Sucesso, Lisbon, Portugal. (Courtesy of Caroline Bowden)

The context of conflict and the subjugation of Ireland and the Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries seems to have militated against the survival and founding of convents.

Ireland was officially a Protestant state. The head of state in the late 16th century was Queen Elizabeth I, and then James I came to the throne in the early part of the 17th century. The established church in Ireland was the Protestant Church, so Catholicism was operating as an illegal institution. It was a unique context because although Ireland was officially Protestant, the vast majority of the population retained allegiance to Catholicism, and so the state ran into a lot of difficulty in trying to suppress Catholicism.

Religious orders were a thorn in the side of the state and official government in Dublin. They played a major role in terms of encouraging observance of the Roman Catholic faith by the lay population, and they maintained a connection between Ireland and Catholic Europe through their international connections.

The onset of the Cromwellian conquest was devastating in Ireland, and members of the church were persecuted. There was a mass exodus from Ireland. Catholic powers like Spain came to the aid of the Irish through connections that had been built via Irish religious like Daniel O'Daly and Francis Nugent of the Irish Capuchins.

The woman who is featured on the front cover of my book is Honoria Megaen. It is from a fresco in Sicily. Honoria was a Dominican tertiary affiliated with the Dominican priory of Burrishoole in County Mayo. The priory was attacked by Cromwellian forces. Two of the sisters — Honoria Megaen and Honoria Burke, another Dominican tertiary — were pursued by soldiers; they were caught, stripped and so badly beaten that they both subsequently died of their injuries. A report about this harrowing incident was sent by eyewitnesses to Dominican friars, and details were circulated at the 1656 Dominican general chapter in Rome.

What is fascinating is that the story of Honoria Megaen's life in a very isolated part of the west coast of Ireland made its way into fresco depicting the pantheon of notable Dominican martyrs in a monastery in Taormina, Sicily. This fresco held her up as a martyr for the Catholic Church.

Bronagh McShane sits in the nuns' choir at the Convento de Nossa Senhora do Bom Sucesso, Lisbon, Portugal, in September 2015. (Courtesy of Caroline Bowden)

One of the primary charisms of many Irish apostolic congregations founded in the 19th century was education. What did you discover about the role of women's orders in education in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland?

There were foundations of Poor Clares, Dominicans, Augustinians and Carmelites, but none of them was engaged in education at this stage. It was not part of their vocation and their mission. An exception is the Benedictines, who returned from the Continent in the 1680s and established a school alongside their convent in Dublin.

While there were a few instances of Benedictines before the Henrician dissolution of the monasteries [1536-1541], the Augustinians were the predominant order for women religious in Ireland at the time. This is interesting because the Augustinians don't really lead the way in terms of the revival of female religious life in Ireland in the post-Reformation period.

In 1629, the Poor Clares are the first order of women that establish themselves in the aftermath of the Henrician suppression of monasteries and convents. They remained the predominant order in Ireland in the 17th century. Next were the Dominicans. An Augustinian foundation of nuns was established in Galway in 1646, but it was very short-lived. The onset of the Cromwellian campaign saw the dispersal of the community along with the Poor Clares and Dominicans, and later, the Augustinians did not reappear in Ireland to the same extent that the Poor Clares and Dominicans did.

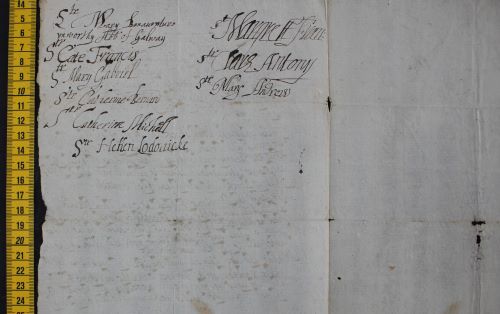

Poor Clare nuns' signatures on a 1647 document (Courtesy of the Poor Clare Monastery Archive, Galway City)

Research for a book like yours involves a lot of analysis and trawling through archives. Was there any nugget that really captured your imagination?

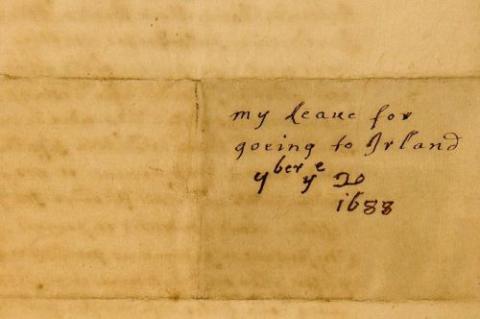

The famous female Benedictine of this period was Kilkenny-born Mary Butler, who was abbess of Ypres. She was schooled and trained in the English Benedictine convent in Ghent, where she had family relations. She subsequently took on the role of abbess of the Irish Benedictine convent in Ypres. Then, in 1688, she undertook a mission at the request of King James II to return to Ireland and establish a Benedictine convent of women religious in Dublin.

We actually have her surviving passport! It is held in Kylemore Abbey and is signed on the back by her, dated September 1688. This document granted her permission to leave her convent and travel to Ireland.

The Benedictines established themselves in Dublin, but unfortunately, it was a very short-lived foundation because of the onset of the Williamite Wars during which the convent was trashed and the nuns had to escape. They returned to the Continent, and Mary Butler never returned to Ireland but remained in Ypres and died there.

Irish Benedictine Sr. Mary Butler's 1688 "leave for goeing to Irland" (Courtesy of the Benedictine Monastery Archive, Kylemore Abbey, Co. Galway)

How significant was social standing in enabling Irish women to pursue their vocation in this era?

I think social class played a big role. Elite families could afford to send their daughters to the Continent for schooling and cover the expense of travel and the cost of education itself. A lot of the women would have boarded at schools attached to the convents. If they pursued a vocation, their family would have paid a dowry, and they might also have sustained them thereafter in other ways.

The closure of the monasteries in the 16th century really did wipe away options for women. Religious life for women provided an opportunity to receive a level of education that they might not otherwise attain and to exercise a level of authority and leadership within a female community that they wouldn't otherwise have had.

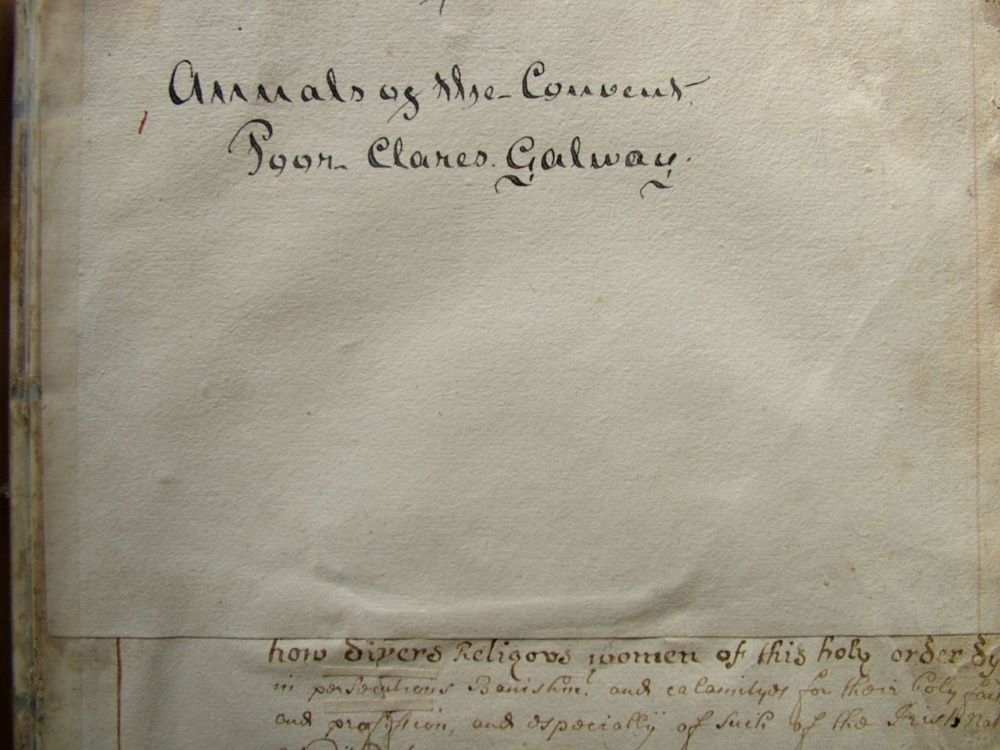

The Poor Clares of Galway are the oldest surviving convent in Ireland and maintain a small but important collection of rare books from the 17th and 18th centuries, including this chronicle kept by Mary Bonaventura Browne. (Courtesy of the Poor Clare Monastery Archive, Galway City)

In the book, I talk about two sisters, Bridget and Mary Nugent, daughters of Richard Nugent, the earl of Westmeath. They were sent to France to be educated by the Sepulchrine Canonesses [Canonesses Regular of the Holy Sepulchre] in Charleville. The nuns were to provide them with a level of education befitting their rank as elite women. We don't have any evidence that either of them became a nun.

They are interesting because they show the networks that were operating within these elite families to ensure that their daughters gained an appropriate education in Europe and that they would be properly trained in Counter-Reformation Catholicism. It also underlines the interplay between Irish male religious and the education of Irish women because Francis Lavalin Nugent [1569-1635], who was the founder of the Irish Capuchin mission, was a relative of Richard Nugent. He was tasked by the earl with assisting his daughters to travel to Charleville, where the Irish Capuchins had a college.

Advertisement

A number of Irish male religious who were trained in the colleges of Europe returned to Ireland to spread the message of Counter-Reformation Catholicism and help women pursue a vocation in Europe. An important figure in this story is Daniel O'Daly, the Dominican friar from County Kerry. He was very active in European circles in terms of diplomacy and through his connections with European royal families. He founded the Irish Dominican College of Corpo Santo in Lisbon in 1634. Recognizing the need for an Irish convent for women religious in Lisbon, he established the Dominican Bom Sucesso convent, the first Irish foundation in Europe in this period for women religious. He traveled to Ireland to seek members for this new foundation.

Other important male figures are Jesuits Henry Fitzsimon and Robert Rochfort. Rochfort assisted Irish women who wanted to join the English Poor Clare convent in Gravelines in modern-day northern France. I was able to locate a grant from the Archduchess Isabella [Clare Eugenia, daughter of Philip II of Spain] to the Poor Clares.

It is fascinating to see how these nuns are communicating with and in correspondence with the highest levels of power and authority in the regions within which they are operating. Far from being shut away behind closed doors, these women were operating in important power networks and were very much at the heart of European diplomacy.