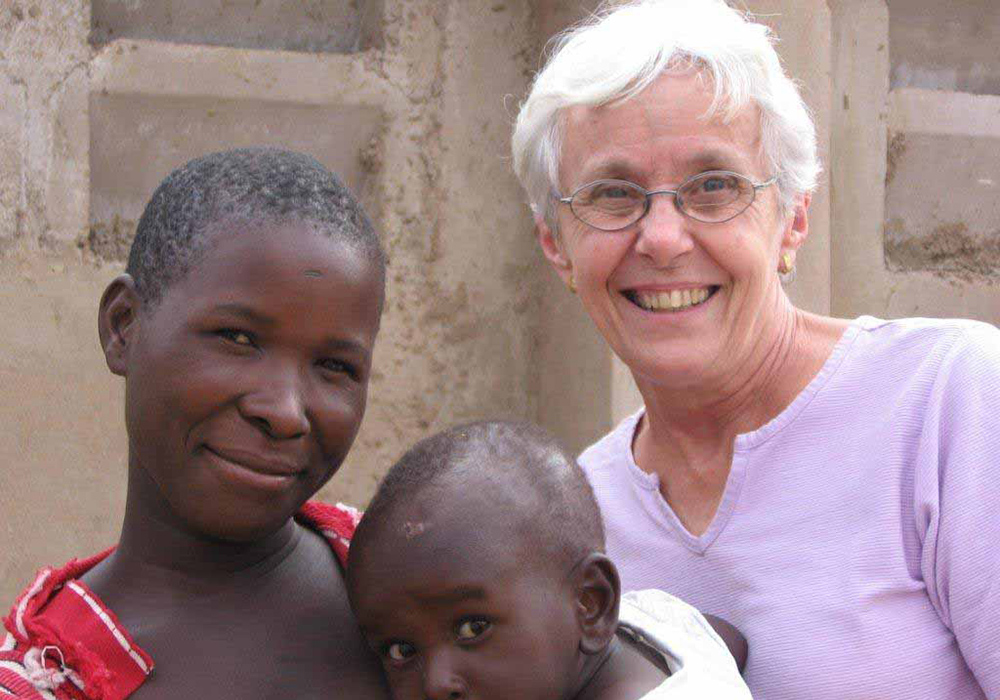

Sr. Connie Krautkremer of the New York-based Maryknoll Sisters served for nearly 50 years in Tanzania. Here she is with a mother and child she worked with during that time. (Courtesy of Sr. Connie Krautkremer)

Sr. Connie Krautkremer, a New York-based Maryknoll Sister and a Minnesota native, spent nearly 50 years serving in Tanzania.

Her time in various locations around the East African country first involved counseling adolescent girls, and later, serving women as they navigated issues of family, rights and faith as the AIDS crisis raged in the area. Time dialoguing with people of varied beliefs and a lifelong bent toward creation spirituality have particularly influenced her faith, she told Global Sisters Report recently. She spent her entire time of service in Tanzania, returning periodically during that time to the Maryknoll Sisters Center in Maryknoll, New York, where she's currently working as personnel director, after leaving Tanzania in 2015.

According to her profile on the Maryknoll Sisters website, Krautkremer holds a degree in biology from St. Catherine's College, which she earned in 1965, the same year she joined the congregation at the Valley Park, Missouri, Maryknoll Sisters Novitiate. At the Maryknoll center in New York, the profile states, she pronounced her first vows in 1968.

Sr. Connie Krautkremer served women in Tanzania until 2015. (Courtesy of Sr. Connie Krautkremer)

Global Sisters Report: Let's talk about your work in Tanzania with women and how you served that population.

Krautkremer: I was teaching high school science [biology]. … At the time, in 1969, there were only a couple of high schools for girls in Tanzania. … I was assigned to a school, so I started teaching girls almost immediately. … I did a lot of counseling — listening to teenage girls talking about struggles they were having in family, with their classmates.

With women, I worked with small women's groups, asking if they had an experience of being sexually abused or harassed in their lives. When I first started this, it was, "No, no." Then, I started giving examples of what harassment and abuse looked like, and the groups became alive with stories of their own experiences.

Sr. Connie Krautkremer's work in Tanzania included meeting with small discussion groups to talk about women's rights and converse about the Bible. (Courtesy of Sr. Connie Krautkremer)

[Later,] there was a United Nations conference on women in Beijing. Some Tanzanian women leaders went to that meeting and came back to Tanzania, and the whole education and awareness among women about women's rights, sexual harassment, all kinds of stuff, just grew within the country. It just grew and grew and grew. By 2015, when I was thinking of leaving, I realized I had really worked myself out of the job.

What did working yourself out of a job look like?

The women I had worked with, plus other leaders, were now taking over this work and doing it in a much better way than I could. One example of this was one of my [biology] students.

She could never sit down. She was so talkative — one of those students you just want to say, "Oh, come on!" She eventually started a center — a big center for abused women in one of the main cities in Tanzania. Years later, I ran into her and she had a place for women who were abused. She was a real leader in that area.

What other types of work did you do with women in Tanzania?

During the time of the AIDS pandemic in Tanzania, many of the women were living with AIDS, or they were widows and grandmothers taking care of orphaned grandchildren. At this time, women were meeting together and talking to one another about how they were dealing with the stresses of AIDS in their own lives and with their children. … [We spoke of] the importance of getting a will, so that if a husband died, his family did not come and want the children back.

Some of the things regarding culture and laws of Tanzania, I wasn't familiar with. But they knew, so then they began to draw on what they knew from their cultures — the difficulties and the blessings and the laws of Tanzania. They were able to bring that in, and learn from one another, and I learned from that also.

Advertisement

Were there any government programs or policies that impacted your work?

The United States government started a program called PEPFAR [President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief], which is now under scrutiny in Congress about whether it should be continued. It was a U.S. government program, which was providing antiretroviral drugs to Tanzania and other countries. It saved the lives of millions of people. There were no drugs available at the time we began to do this work.

Once that program came, and the government of Tanzania was able to set it up, drugs became available. [There were] educational programs so that people who were living with AIDS could live. Teachers could now teach. Farmers could go back and farm their fields. Children were not orphaned anymore. It changed the quality of life for millions of people, and it's continued to do that. I hear about it, and some people are saying, "Oh, it's providing abortion."

That is not true. I think recently, someone said, "If anything, it's pro-life." It is — this program that saved the lives of millions.

Let's hear about your faith in general and how it's changed over the course of your service and how your work influenced that.

I went to Tanzania to share skills that I had and to learn. … I wanted to understand the values and traditional practices of people. I wanted to know how their faith [was] lived, was practiced, was shared. I was curious about all of that. I worked with women and young girls of many different faiths — Muslims and Christians together. All different denominations, so to speak.

We prayed together, we shared together. I always tried to be inclusive. … I was baptized as a Catholic, but let's say my faith in God has expanded to be much more inclusive and appreciative of others.

My spirituality is really creation-centered spirituality. … I realized growing up on a farm, being a biology and a science teacher, my spirituality has often been deeply based in creation — the world about me. … This has grown to include all of life, all of creation, not just the beautiful parts (but also) people to include my enemies, so to speak. We're all part of one another, and we're neighbors. At this time, part of my spirituality is about having difficult conversations, doing that respectfully and with others who are different. … That's where my spirituality is leading me now.

And what's your perspective on the Catholic Church moving forward?

I don't have that much experience with the church in this country. In Tanzania, I would say the small groups are the groups of women who are actively involved in the church, taking leadership. … My hope is in the women who are already taking leadership roles — that they will be able to support one another and continue to exercise all their leadership skills.