A girl stands at a Food for the Poor feeding center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where families receive meals or provisions to take home. (Courtesy of Food for the Poor)

The humanitarian situation in Haiti, dire even in normal times, has worsened in recent months because of violence on the streets, stalling work throughout the country that is performed by sisters and by church-based relief agencies who work with sister congregations.

"Since September, the political situation has become worse, and so nobody has been able to go into the city," Sr. Denise Desil, mother general of the Little Sisters of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus, a Haiti-based congregation, told GSR, referring to the capital of Port-au-Prince. The result, she said, is that sisters in her congregation are more or less "staying home" in the congregational motherhouse in nearby Rivière-Froide because "we are not free to move out ... it is not safe to travel."

More than 40 people have been killed and dozens injured in the wake of street protests in Port-au-Prince and other major cities since September, the Associated Press reported.

"Obviously, everyone in Haiti is being seriously and adversely affected by the chaos," said Sr. Marilyn Lacey, executive director of the humanitarian agency Mercy Beyond Borders and a member of the Religious Sisters of Mercy.

Lacey told GSR her program funds scholarships for 174 girls in the Gros Morne area of northern Haiti and several more at universities in Port-au-Prince, but the students are unable to attend their schools.

Sr. Denise Desil, 66, the mother general of the Little Sisters of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus in Haiti, at a September 2017 service of perpetual profession for three new sisters (GSR file photo/Chris Herlinger)

"All schools have been shut down nationwide since early September," she said.

The immediate cause of the protests, many of which have been peaceful, is unhappiness with the leadership of President Jovenel Moïse, a Haitian businessman who was a political neophyte when he was elected in 2016.

Charges of electoral fraud have dogged Moïse since the elections, and Moïse's political opponents say his administration has not done enough to deal with long-standing problems of government corruption. They also say his government is mishandling Haiti's already-struggling economy. His opponents are calling on the president to resign.

Moïse, who has vowed not to step down, has pleaded for national unity.

"The country is more than divided, the country is torn apart," Moïse said late last month, as reported by The Associated Press.

The struggle between Moïse "and a surging opposition movement, which coupled with economic struggle and corruption have led to soaring prices of basic goods, crumbling healthcare facilities, and pushed the country to the brink of collapse," the United Nations said Nov. 1. The U.N. noted that the majority of those killed died of gunshot wounds, 19 of those apparently "at the hands of security forces, and others by armed demonstrators or unknown perpetrators."

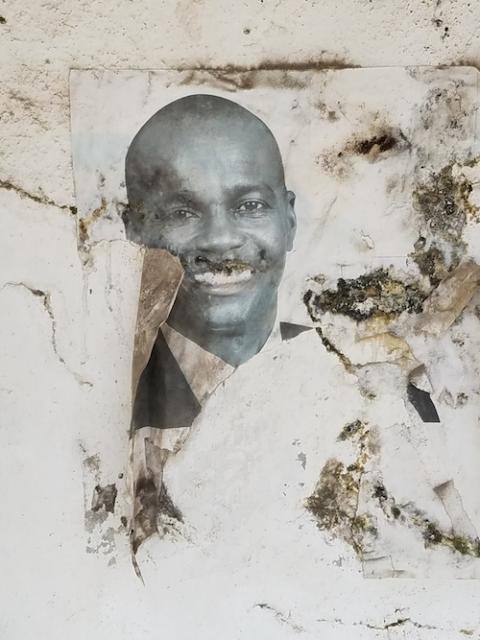

A worn 2016 election poster on the streets of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, of President Jovenel Moise (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Though there is a long history of political street protests in Haiti, the current challenge for day-to-day life in many Haitian cities is the paralyzing street violence, sometimes by gang members, say the sisters and others involved in humanitarian work.

The picture is grim in other ways.

"Costs for ordinary things like food and fuel have skyrocketed due to transport blockades. People hunker down in their homes, fearful of venturing out," Lacey said. "Street gangs have stepped up their activity and power."

Sr. Sissy Corr, a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur who works with its Notre Dame Mission Volunteers ministry, told GSR that the current protests have to be seen in the context of a yearlong unfolding of events, noting that frequent gunshots and roadblocks have been the norm since February, accompanied later in the year by crippling inflation. The "tipping point," she said, came in late August, "when there was no fuel for generators and huge rises in the cost of gasoline."

"There's underlying fear," she said. "You sense it in the air."

Corr said she feels those putting up road blocks are "young guys wearing bandanas without jobs" who just want an opportunity for work so they can provide for their families. Overall, she said, Haitians now "are just hungry and scrapping by to get some money for food. They hunger for a better Haiti."

The situation has frustrated sisters, who are used to conducting their ministry against great odds, Desil said. The challenges of security, travel and dealing with potential gang threats have stopped some work, such as teaching, she said, and slowed (though not fully halted) the sisters' work in providing food for children in an orphanage in Artibonite in northern Haiti.

Desil said one sister in her congregation has not been able to get her needed diabetic medications. Long-term, she said, "we can't live in this condition."

Those involved in humanitarian ministry must try to figure out when they can eke out some work around those days when it is not possible to get around because of security worries.

"Protesters allow us free days such as Saturday and Sunday so that we can go out to buy food and medication," said Korean Sr. Matthias Choi, who heads the Haiti mission of the Kkottongnae Sisters of Jesus, a South Korean congregation with a 30-year history of work in poor communities throughout the world. However, the situation on the streets often limits that work to serving elderly residents of a senior citizens' village.

"It seems like the cycle has become three to five days of demonstrations and one to two days off," she told GSR.

Though Choi said members of her congregation are not in any immediate danger, she said they have had to deal with shortages of rice; fuel, such as propane and diesel gas; gauze for wounds; milk for children; and medication.

Lacey said her organization's staff members have had to fly from Port-au-Prince to Gonaives in northern Haiti, which is normally a three-hour drive, "since the main north-south highway has dozens of daily blockades at which you pay multiple bribes to pass, if lucky, or get robbed or attacked if unlucky."

Left: Mercy Sr. Marilyn Lacey, executive director of the humanitarian agency Mercy Beyond Borders (Courtesy of Mercy Beyond Borders); Right: Sr. Matthias Choi, head of the Haiti mission of the Kkottongnae Sisters of Jesus (GSR file photo/Chris Herlinger)

Food for the Poor sends bags of rice and beans by boat to La Gonave Island from a private port. Security issues prevent the boats from shipping provisions from a public port in Port-au-Prince. (Courtesy of Food for the Poor)

'More life in the street' with tenuous improvement

There are tentative signs that the situation might be improving.

Corr said an industrial-sized bakery she helps run in the city of Les Cayes closed in October because of the insecurity in the coastal city. But the facility was scheduled to reopen Nov. 26 because of availability of fuel and baking ingredients plus slightly improved security.

Corr left Haiti in September because of a death in the family and has not returned to Haiti since then. Interviewed by GSR from Florida, she said she hopes to return as soon as possible, though she is still concerned about safety.

"What's changed?" she said. "I want to be prudent."

The situation in Port-au-Prince has improved a bit since late November, said Sr. Annamma Augustine, an Indian Missionary Sister of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. "There is more life in the street," she said.

But Desil said she thinks the overall situation is not improving. Schools remain closed, people are afraid to go out, and gunmen are still shooting. "Things are not better," she said. "We are tired of this situation."

The situation is not uniformly dire across the country, but the effects of the stalemate are being felt everywhere.

Augustine told GSR that while the congregation has had to discontinue its ministries in Port-au-Prince for now, its ministries outside the capital are still running, including in the dioceses of Port-de-Paix in northern Haiti and Les Cayes in southern Haiti.

Work in and near Ouanaminthe, not far from the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic in northern Haiti, continues, and the overall situation is stable, said Colombian Sr. Alexandra Bonilla Leonel, a member of the Sisters of St. John the Evangelist, also known as the Juanistas. However, the paralysis in major cities like Port-au-Prince is causing prices for food and other goods to rise, she said.

"The economic impact is being felt," Leonel said.

Left: Sr. Annamma Augustine, an Indian Missionary Sister of the Immaculate Heart; Right: Colombian Sr. Alexandra Bonilla Leonel, a member of the Sisters of St. John the Evangelist, also known as the Juanistas (GSR file photos/Chris Herlinger)

Humanitarian efforts continue

Lacey and others are concerned about the effects of the situation long-term.

"It goes on and on. Protestors have one goal: Shut down the country until Moïses leaves. Meanwhile, of course, it is really hurting the common people the most," she said.

Other humanitarian efforts continue doggedly despite serious challenges. In a Nov. 21 statement to GSR from the Florida-based humanitarian organization Food for the Poor, agency director Angel Aloma said, "Getting food out to the areas in the countryside has been a challenge. Our workers have been shot at, and in one case one of our drivers was injured."

Some families have still been able to make it to a Food for the Poor feeding center in Port-au-Prince, he said.

Advertisement

"Even when our workers could not cook the usual meals, they would package up dry provisions such as beans and rice and give that to the hungry who were able to make it to the feeding center," Aloma said.

In another case, the agency sent bags of rice and beans by boat to La Gonave Island, population 87,000, "which has been severely impacted by the unrest," said agency spokeswoman Kathy Skipper. It was not possible to ship food and water from a port in Port-au-Prince because of security issues, she said, so the agency found someone with a private port.

"It has been challenging, and we have been saddened to see how long it has continued. But we have seen these cycles in Haiti before and we pray that soon it will be peaceful enough to return to our normal operations," Aloma said.

A woman receives a hot meal for her and her family at a Food for the Poor feeding center in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. (Courtesy of Food for the Poor)

Chris Bessey, the Haiti country director for Baltimore-based Catholic Relief Services, echoed those sentiments in an interview with GSR, saying, "We're doing everything we can to keep things going."

Though hopeful that the situation will change, Bessey said he sometimes worries it could "go on for months or years" if a political solution to the crisis is not found, noting that the "masses of people" are caught in the middle of a political struggle.

Bessey said he does not believe donors to CRS's work in Haiti will give up on the country, saying there is a loyal donor base in the United States for work in Haiti.

"I know there is a strong connection [in the United States] with the people of Haiti," he said, citing individual, organizational, diocesan and parish-to-parish ties.

Boyer Jean Odlin, a young professional who has been out of work since Hurricane Matthew hit Haiti in 2016, is among those hoping for change.

He moved from the southern coastal city of Les Cayes to the island of Île-à-Vache in May in hopes of a better life. Though day-to-day life on the island is not as difficult as it is in the large cities like Port-au-Prince, Odlin told GSR that one example of the difficulties of life now in urban areas is that of armed gunmen stopping cars and demanding money, he said.

The only solution to the current political stalemate, he said, is to end the "fighting between the opposition and the government." As it is now, he said, the situation in Haiti has become "unlivable. There is so much misery right now."

[Chris Herlinger is GSR international correspondent. His email address is [email protected].]