Svitlana Kruchynska, 57, a recent arrival from Melitopol, Ukraine, on a street in Krakow, Poland. She is living with her daughter and another woman at a Dominican convent outside of the city. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

A month ago today, Svitlana Kruchynska stepped outside her home in Melitopol, Ukraine, to walk her two dogs early in the morning despite bracing, below-freezing temperatures. That was part of her normal morning ritual — but it was the last thing that proved normal or routine for the 57-year-old librarian, her 23-year-old daughter and millions of their fellow Ukrainians.

The Russian bombardments targeting Melitopol — a city renowned for its fruit trees and verdant gardens and parks — began shortly after 5 a.m. the morning of Feb. 24. Waking at 5:10 a.m., the blasts startled but did not entirely surprise Kruchynska or her daughter. Residents of Melitopol had become accustomed to Ukrainian military exercises as the threat of war intensified, so the two women tried to think the best — that what they were hearing was a kind of new normal.

But when Kruchynska saw warplanes overhead, she realized war — threatened for weeks and a prospect for years — had begun. The city with a population of 150,000 that lies near the border with the disputed Crimean Peninsula and where many Ukrainians still speak Russian — a holdover from Soviet days — was under attack by Russian forces.

With the escalating din of bombings, shootings and shattered glass, Kruchynska and her daughter realized they had to flee.

"We'd be under the gun," Kruchynska's daughter recalled in an interview along with her mother in a park near Krakow's old city on a bright sunny Sunday afternoon, just weeks after they had fled their homeland.

Advertisement

Kruchynska, speaking through a translator, acknowledged that she was a bit hesitant at first — Where would they go? she asked her daughter. But the younger woman convinced her mother that it was best to leave, a hunch that proved correct given that Russian tanks entered Melitopol a day later.

The daughter, who did not want to be identified by name publicly out of security concerns, said in the March 13 interview she was worried for her and her mother's safety.

The collection of blue and yellow Ukrainian flags throughout the family home identified them as nationalists and could put the family at risk, the daughter said. The family could be targeted, she warned her mother. "We thought it would be best to leave," she said.

And so, they fled in the family car, with neither Kruchynska nor her daughter packing suitcases or even passports. All they had with them were the clothes they were wearing and their national identity cards.

They left almost immediately, accompanied by the two dogs, and saw few cars on the road, though they did see some wreckage of burned-out vehicles along the way. Luckily, once out of Melitopol they did not hear further explosions.

New arrivals from war-torn Ukraine arrive at the train station in Przemyśl, in southeastern Poland, destined for other cities in Poland or elsewhere in Europe. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

The women decided to meet up with the mother of the daughter's boyfriend who lived in the city of Zaporizhia, about 80 miles north. They stayed there three days but after that city's airport was targeted and bombed by Russian forces, the women decided to head west, accompanied by the boyfriend's mother.

Without a change of clothes, they continued their journey, dogs in tow, and drove nearly 400 miles to spend one night in the city of Khmelnytski and eventually ended up, as have many in the last month, in the western border city of Lviv.

After three nights in Lviv, the women crossed the border into Poland on March 1. After a few short hours of sleep in the car, they arrived in Krakow a day later.

Due to the efforts of a Caritas volunteer at the border, they found shelter at a convent of Dominican sisters, about an hour's drive from Krakow. The sisters, about 40 in all, are housing about 20 arrivals — children, women and one elderly man.

And the sisters have welcomed the dogs — one 3 pounds and the other a much larger animal at 30 pounds. The pets have survived the arduous journey fine, Kruchynska said. "They have enough food."

'We are not going to stay in Poland,' Svitlana Kruchynska said — a statement that reflects the women's steely determination to return to Ukraine as quickly as possible.

Along with the dogs, the three women now live together in a single cramped room. They are tired and anxious — the circles under Kruchynska's bloodshot gray-blue eyes attest to that — but are thankful for the hospitality shown them by the sisters. "We've been welcomed very well by the Dominican sisters," Kruchynska said.

"The sisters are all good," she said, adding that it helps that two Polish sisters at the convent served in Ukraine and speak Ukrainian, while another sister from Belarus can speak Russian to the family.

The overall welcome by Poles and by Ukrainians already living in Poland has been warm and appreciated, Kruchynska said. As one example, officials at a consulate office in Krakow — where the arrivals have to wait in long lines to receive the papers allowing them to stay in Poland — provided food and words of comfort.

As for the future, the Dominican sisters have said that "we can stay as long as we need to," Kruchynska said. "But we so want to be home, and for this war to be over."

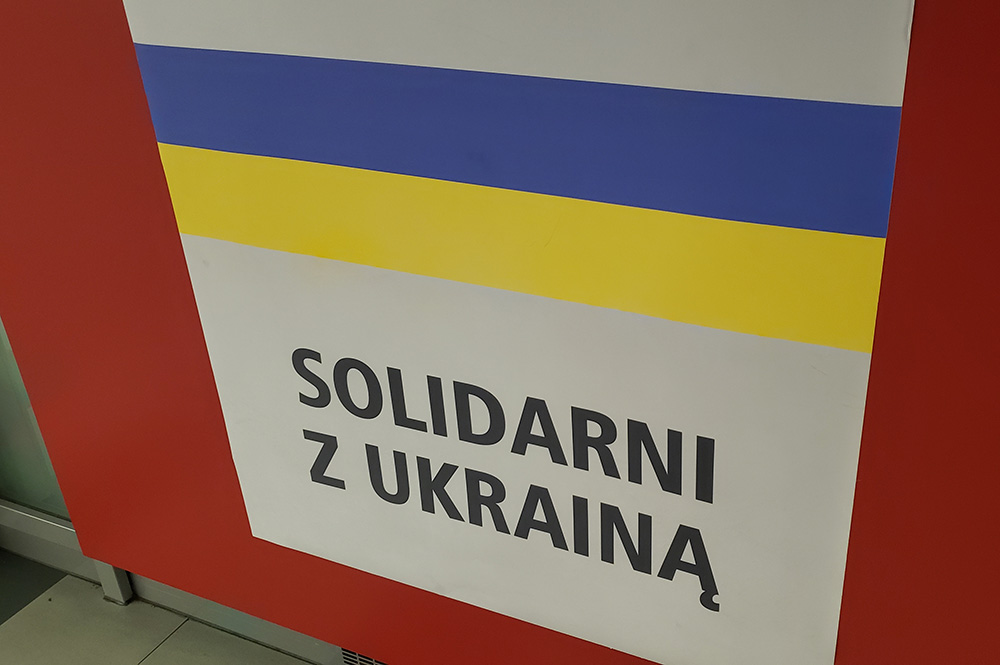

One of many signs of solidarity between Poland and Ukraine seen on the streets of Krakow, Poland (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

She paused. "We are not going to stay in Poland," Kruchynska said — a statement that reflects the women's steely determination to return to Ukraine as quickly as possible.

"We're praying for peace, praying for peace in Ukraine," she said, adding that she knows that Pope Francis and the church around the world is doing the same. "Pray," Kruchynska said when asked what the pope should do for Ukraine.

Convents house arrivals

Prayers are comforting the 3 million Ukrainians who have fled their country in the last month, but so are the many acts of hospitality shown by sisters to people like Kruchynska and her daughter and thousands of other recent arrivals.

The Council of Major Superiors of Women's Religious Congregations in Poland said in a March 15 statement that 924 convents in Poland and 98 in Ukraine "are providing spiritual, psychological, medical, and material help," with each of the nearly 150 Polish religious congregations operating in Poland and Ukraine assisting those displaced by the war.

Housing has been organized in 498 convents in Poland and 76 in Ukraine — all convents run by Polish congregations — the statement said, with 3,060 children, 2,420 families and approximately 2,950 adults being welcomed by sisters.

New refugees, some holding pets, arriving from Ukraine board vans at a reception center at Przemyśl, in southeastern Poland, destined for other cities in Poland or elsewhere in Europe. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

Aside from providing housing, other responses by sisters include "preparing and distributing hot meals, food, sanitary products, clothing, and blankets," the statement said.

In Poland, sisters have helped transport arrivals, assisted refugees in finding work in Poland, helped the new arrivals at welcome sites and helped Ukrainian children enter Polish schools, the statement said. As with Kruchynska and the two other women, sisters are helping translate for the arrivals.

While most refugees are women and children, sisters are also assisting elderly and disabled persons find shelter either at convents or at institutions run by sisters.

"In Poland, religious communities constantly collect food and hygiene products which are sent to Ukraine, given to refugees, or given to houses run by congregations where war victims receive help," the statement said. "The congregations also make financial donations and transmit funds through their foundations."

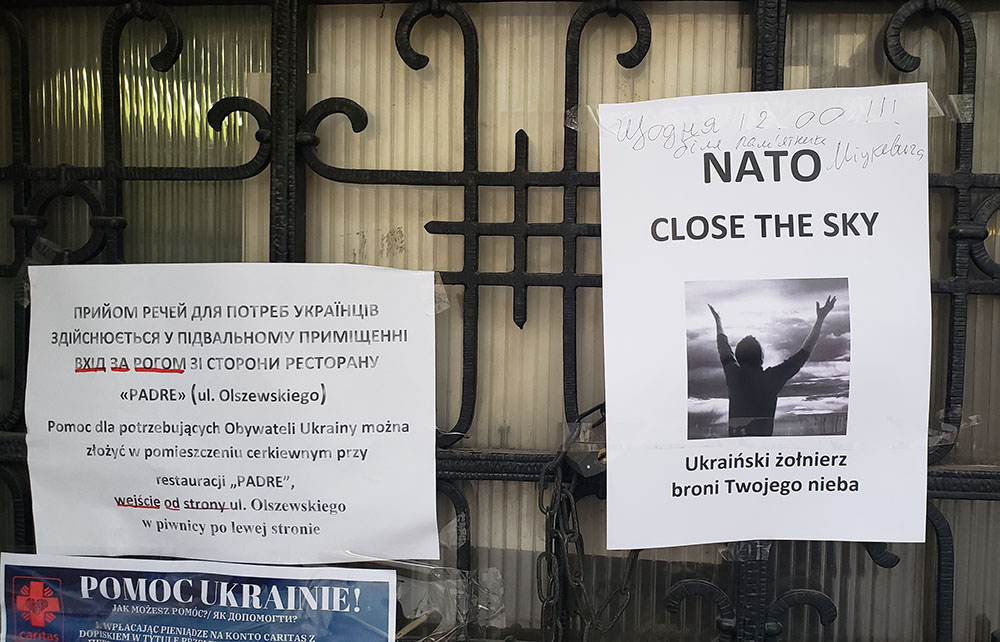

A sign on the doors of the Ukrainian Catholic Church at the center of Krakow, Poland, calls for a NATO-led "No Fly-Zone" over Ukraine. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

The statement noted that, in addition to the work within Poland, there are more than 332 sisters from Polish religious congregations working in Ukraine.

In an email to GSR, Sr. Dolores Dorota Zok, the provincial leader of the Mission Congregation Servants of the Holy Spirit in Poland and president of Council of Major Superiors of Religious Orders in Poland, said that sisters from Polish congregations both in Poland and in Ukraine "are very excited to be able to help our brothers and sisters from Ukraine," calling it a "beautiful service" and ministry — "very human, very spiritual."

Zok called the war in Ukraine "such an injustice."

'Freedom, beauty, identity'

Sitting on a park bench with her daughter and the boyfriend's mother looking on, Kruchynska acknowledged the severity of that injustice: She feels bitterness toward Russian President Vladimir Putin and his government.

But Kruchynska does not feel such anger toward "ordinary Russians," saying she does not believe that they truly understand what is happening in Ukraine right now.

Proud of the global support and solidarity shown Ukraine — including military volunteers from other countries coming to fight for the country — Kruchynska said she does not want to focus on what could make her angry.

Even in moments of silence, like at the convent, 'we hear sirens in our heads.'

Still, she acknowledges the cost — even physical cost — of the effects of war. Kruchynska stiffens at the memory of sirens in war-besieged Zaporizhzhia. "We heard them all the time," she said. Now, in and around Krakow, she said, she is startled to hear the occasional siren and panics momentarily.

Even in moments of silence, like at the convent, "we hear sirens in our heads."

The war's effects are also felt in other ways. While in Zaporizhzhia, the three women lost all appetite. And after arriving at the convent near Krakow, all they could manage to take in were tea and some cookies. "Nothing tasted good," she said.

A constant worry for the women is the fate of men back at home — the daughter's boyfriend, Kruchynska's 80-year-old father and her 34-year-old son, who is volunteering to bring supplies, clothing and food to Ukrainian soldiers. The women stay in touch with the men via texts and phone calls. For the moment, the men are all right.

Though war always comes as a shock when it finally arrives, Kruchynska's daughter said that those living in cities like Melitopol were perhaps better braced for it, given that Russian and Ukrainian forces have been engaged in battle since 2014 over Crimea and disputed parts of eastern Ukraine.

"Those who live far from that border still can't believe this is happening," she said. But for those living closer to the border, it is a situation that is not quite totally new.

A rally held in the main square of Krakow, Poland, March 13 calls for a NATO-led "No-Fly Zone" over Ukraine. (GSR photo/Chris Herlinger)

"That background is important," the daughter noted, saying that her family and others prepared gift packages of food and other supplies for those fighting at the border for years. That was another reason why it was imperative to leave Melitopol.

"This is still all so difficult," she said.

Kruchynska nodded at her daughter, but her face brightened when asked what it means to be Ukrainian.

"It means freedom, it means beauty, it means identity," she said, beaming. "We want to be an independent country," she said, suddenly crying quietly. "We are a joyous people."

Kruchynska repeated her hope that the family will be able to return to Ukraine shortly — both as a homecoming and also to welcome visitors to a country she and her family dearly love. "We are waiting to return. We don't know when but we hope it won't be long."

After an hour's conversation, Kruchynska said she would rather dwell on fond memories, recalling the pride of Melitopol: its gardens, parks and fruit trees. "Our city's emblem is the cherry tree," she said, tearing up at the memory.

She extended her hand.

"Come," she said. "Come visit. It will be cherry time."