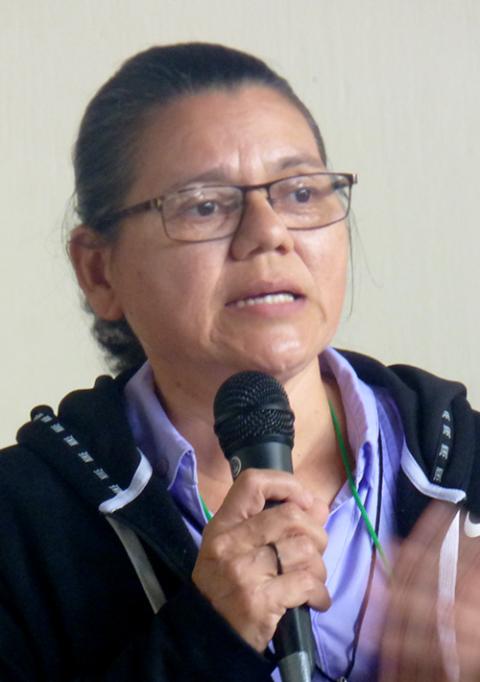

During a seminar on human trafficking Aug. 18 in Guatemala City, Carmelite Missionary Sr. Verónica Cortez Méndez talks to a group from the Confederation of Latin American Religious about Costa Rica's response to migrants who travel through the country. As migration increases, so do the chances of potential human-trafficking victims, said experts who spoke to the group. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

They were difficult stories for anyone to hear, much less talk about. But some of the women religious in the room had come face to face with human trafficking and had heard similar stories before.

Both speakers at a seminar against human trafficking — a man and a woman — spoke to the sisters of how love gone wrong led to a nightmare.

In the man's case, it was of a wife who had been exhibiting odd behavior. He later found that she had been offering their daughters to men to be sexually abused.

In the woman's case, it was the story of a man who told her he loved her, took her away from her family at a young age, then turned her into a commercial sex worker, threatening to take her son away if she stopped working.

They put a face on the reality that women religious, and others who attended the Aug. 18-20 seminar in Guatemala City, gathered to battle. The event, organized by the Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean Religious (CLAR), is part of worldwide anti-human-trafficking efforts by Catholic sisters.

The sisters from throughout Latin America — gathered in person for the first time since the coronavirus pandemic — began to share experiences, learn more about the topic and collaborate on anti-trafficking efforts.

'This is our mission and this is our time: to care for life, to serve life and to defend life.'

— Sr. Daniela Cannavina

Like other groups that bring together women religious from around the globe to fight for social justice, consecrated life in Latin America has a mission when it comes to human trafficking, said Sr. Daniela Cannavina, CLAR's general secretary and a member of the Capuchin Sisters of Mother Rubatto. She called the phenomenon a "profound violence to the body of humanity."

"This is our mission and this is our time: to care for life, to serve life and to defend life," Cannavina told the group, which included members from Brazil, El Salvador, Mexico, and Chile.

Some spoke about the direct contact they have had with victims and survivors, often in isolated regions, such as South American mining and agricultural towns, or heavily traveled migration routes, like the U.S.-Mexico border and the Darién Gap, which have increasingly become magnets for human trafficking.

Lizbeth Gramajo Bauer, of the Network of Jesuits with Migrants in Central America, an anthropologist who spoke to the group, said chances of becoming a victim increase in times of great migration, as Latin America and the Caribbean are now experiencing. That's because, in desperation, people often turn to smugglers to get them to where they want to go — legally or otherwise.

Sr. Carmen Ugarte, a member of the Oblate Sisters of the Holy Redeemer, listens to a survivor of human trafficking during a seminar on the topic Aug. 18 in Guatemala City. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

In that hidden world, if they are raped, beaten, abducted or forced by criminals to do something they don't want to do, they feel they can't run to authorities for help because they lack legal standing, Gramajo said. And so, irregular migration and human trafficking become twin problems that go hand in hand, she said.

In small groups, the sisters — as well as men religious and laypeople in the room with them — gathered to talk about situations they've seen or heard, and confided in one another about what keeps them up at night: migrant women given a pill to prevent a fetus from implanting, in case the women become pregnant when they're raped; the reticence of crime victims to contact authorities because they have no legal permission to be in the countries they're traveling through; governments that have no interest in fixing problems to keep citizens in their home countries because they depend on remittances (the money migrants send home) to prop up a country's coffers.

Trafficking is a well-organized crime, from top to bottom, said Sr. Verónica Cortez Méndez, a Carmelite Missionary from San José, Costa Rica. She lamented how "human beings have become insensitive enough to negotiate [the life of] another human being."

'Human beings have become insensitive enough to negotiate [the life of] another human being.'

— Sr. Verónica Cortez Méndez

Along with other sisters from the seminar, she boarded a bus for an unusual outdoor session that took the women religious through Guatemala City’s “La Linea,” a dangerous red light district near defunct train tracks, where prostitution began in the 1940s with the arrival of workers bringing in goods to a growing city. In La Linea’s best economic days, when the train operated, shacks began springing up. That’s where workers started soliciting services that continued even after the train stopped working in the late 1960s.

From inside the bus, the sisters looked out the window at a new police station near the shacks where the prostitution of women — and increasingly gay men — was taking place out in the open, knowing all the while that some of the most dangerous activity is the kind you can't see.

Sr. Janeth Rodríguez González, of the Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer, explained to the group a set of statistics about the estimated 27.6 million human-trafficking victims worldwide and at the regional level. The number of children experiencing human trafficking in Central America is increasing, as well as the number of men, she said.

On the other hand, a set of numbers the United Nations Office on Crime and Drugs unveiled in early 2023 seemed encouraging at first, Sister Rodríguez said. The report noted that the number of documented victims of human trafficking worldwide in 2020 had decreased 11%, the first drop in 20 years, she noted.

During an Aug. 18 seminar in Guatemala City, Good Shepherd Sr. Janeth Rodríguez González explains statistics showing how human trafficking has gone deeper underground following the coronavirus pandemic. (GSR photo/Rhina Guidos)

But a closer look revealed the reality about the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the detection of human trafficking.

"It drove it into clandestinity," explaining the decrease, Rodríguez said in her presentation to the group.

Initially, like the rest of the world, criminals tried to figure out what the coronavirus meant to their operations. They initially suspended their activities, but the way organizations such as the U.N. Office on Crime and Drugs see it, traffickers saw an opportunity since authorities were limited in the application of the law, given the enormity of the pandemic.

Those who study human trafficking can only estimate that for each victim the world knows about, there may be 20 others who don't come forward or who do not realize they are victims, Rodríguez said.

It was something confirmed by the woman who talked to those in the seminar and said that, for a long time, she didn't realize she was being exploited and abused.

In a statement, the women and men religious in attendance demanded that those responsible, including governments, improve conditions in the region that force men, women and children to migrate and become potential victims.

Advertisement

"The impoverishment of our countries is compounded by economic, political, health, socio-environmental and cultural causes that are aggravated by drug trafficking, corruption, the progressive weakening of democracies, the accumulation of power and the scarce economic growth, which adds new faces to the poor, without any guarantee of security, which increases the risk, vulnerability and the possibility of falling into criminal networks and becoming victims," the statement said.

But they also held responsible the countries of destination where the victims are transported to — like merchandise across borders, from the poorest to the richest countries — where instead of finding help, victims encounter abuse, mistreatment and violations of their rights by those who blame them for their misfortune, the group said.

In the end, those sentiments only contribute to the cycle and those who deal in the trade of people, they said in the statement.

"Public opinion, through media, propagates discriminatory and xenophobic discourse, and criminal groups are aware of and take advantage of this phenomenon through the use of extreme violence and fear."