(Unsplash/Andrew Itaga)

When the Vatican's Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith recently published "Una Caro (One Flesh): In Praise of Monogamy: Doctrinal Note on the Value of Marriage as an Exclusive Union and Mutual Belonging," it did more than restate Catholic teaching on marriage. It revived a troubling pattern in global Catholic discourse: speaking about Africa without listening to Africa. The document's claim that "monogamous marriage in Africa would be considered an exceptional reality, given the widespread practice of polygamy" is empirically weak, culturally reductive and historically reminiscent of older missionary narratives that framed Africa as morally deficient rather than socially complex.

Pastorally, this claim is discouraging for African pastors and theologians. It also confuses African faithful, for whom it misrepresents the beauty of marriage and family life they experience in Africa. Coming at a time when African bishops are still completing a synod on synodality-mandated study on polygamy, the timing and tone of Una Caro raise a deeper question: Why is Africa once again being defined without Africa at the table?

As a liturgist, lawyer, and human-rights advocate who has studied marriage systems in Africa for more than a decade — particularly their implications for women and children — I find the framing in Una Caro deeply concerning. Not because it reaffirms monogamy. That commitment is not in dispute, even among African Catholics and Christians. The problem is how the document arrives at its conclusions, and what it leaves out along the way.

Africa is not a monolith — and polygamy is not its marital norm

Africa is often spoken of in some of the church's documents, such as Una Caro, as though it were a single moral and cultural space. It is not. It is a continent of more than 50 countries, thousands of ethnic groups, and diverse legal, religious and marital traditions. Polygamy exists, yes, but it does not define African marriage and varies from one African country and region to another. Historically, monogamy and polygamy have coexisted in many African societies, shaped by economic conditions, kinship structures, inheritance systems and demographic pressures. In contemporary Africa, monogamous marriage — customary, civil, and Christian — is widespread and growing, particularly in urban centers, among younger generations and within Christian communities. In many countries, civil law recognizes only monogamous marriage. Even where customary law permits polygamy, it is far from universal.

To describe monogamy as "exceptional" in Africa is therefore misleading. It obscures the lived reality of millions of African families who have embraced monogamy for generations.

Worse, it unintentionally reinforces stereotypes that reduce African cultures to a single marital pattern, as though complexity itself were a deviation from moral maturity. This kind of framing echoes earlier missionary assumptions. At the 1910 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh, Western delegates famously identified polygamy and "primitive religion" as the two significant obstacles Christianity would face in Africa. More than a century later, it is unsettling to see one of those same assumptions resurfacing — this time in a Vatican doctrinal note.

A hand holds a wedding ring in this undated illustration photo. (OSV News/CNS archive/Mike Crupi)

Doctrine is clear, pastoral reality is not

The Catholic Church's teaching on marriage is not ambiguous. Marriage is a covenant between one man and one woman, rooted in creation, affirmed by Christ, and elevated to a sacrament. Its essential properties — unity and indissolubility — are not negotiable. But doctrine does not exist in abstraction. It is lived by real people in real social conditions. And in Africa, polygamy is not primarily a rejection of Christian teaching. It is a cultural practice that predates Christianity and is often tied to social protection, lineage continuity, labor demands, infertility stigma and economic survival.

This distinction matters pastorally. When individuals or families in polygamous unions encounter Christianity, conversion does not erase their history. It reorients it. The Gospel calls people toward unity, fidelity and mutual self-gift — but it does so through accompaniment, not erasure.

Here is where Una Caro falters. While it rightly condemns polygamy as incompatible with sacramental marriage, it offers little guidance for addressing the complex human realities that already exist. The result is a pastoral gap — one often filled by exclusion rather than discernment.

Advertisement

When moral clarity produces moral harm

Across Africa, the consequences of this gap are painfully visible. Men and women in polygamous unions — many of them baptized Catholics — are frequently barred from the sacraments, excluded from parish leadership, denied the role of sponsors at baptisms or weddings, and in some cases even refused Christian burial. Most troubling is the instruction sometimes given to men in polygamous unions who seek sacramental marriage: choose one wife and abandon the others.

This practice, intended to defend monogamy, often produces new injustices. Women — frequently economically dependent — are cast aside. Children lose support, stability and social protection. The church, in attempting to regularize one relationship, becomes complicit in the destruction of others.

Catholic moral teaching does not permit such outcomes. While polygamy contradicts conjugal unity, moral action must never generate greater injustice. Abandonment of women and children violates core principles of justice, responsibility and the protection of the vulnerable. Any pastoral approach that increases harm fails its own moral test.

The limits of condemnation

Polygamy is not the only irregular marital situation facing African churches. Divorce, informal unions, syncretistic religious practices and economic pressures shape pastoral life daily. Yet polygamy remains uniquely stigmatized — addressed primarily through prohibition rather than sustained pastoral engagement.

Recent church documents affirm monogamous marriage with renewed clarity. That clarity is welcome. But clarity alone does not convert hearts or transform social structures. When moral norms are repeated without attention to lived reality, they risk becoming static — heard but not received.

The persistence of polygamous unions, even among baptized Christians, is not evidence of moral failure alone. It is evident that pastoral strategies have not adequately addressed the social and economic forces that sustain the practice.

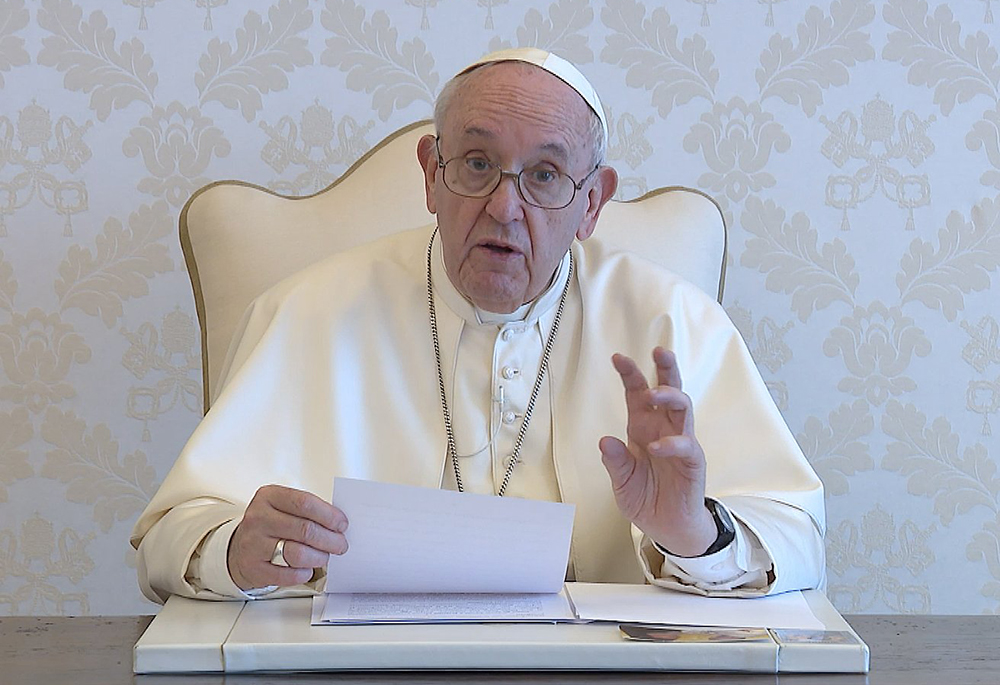

Pope Francis delivers a June 9, 2021, video message to participants of an online forum titled "Where are we with Amoris Laetitia?" dedicated to implementing proposals inspired by his 2016 exhortation of the same name. He said the church must learn to "listen actively to families, and at the same time to involve them as subjects of pastoral care." (CNS screenshot/Vatican Media)

Pastoral discernment and accompaniment

One of the lasting messages of Amoris Laetitia of Pope Francis is the call for pastoral discernment and pastoral accompaniment for families in complex situations. It is the same spirit that animated the extraordinary work of the Symposium of Episcopal Conferences in Africa and Madagascar's (or SECAM) theological commission's study on polygamy, received after a robust and rigorous debate at the 20th plenary assembly of SECAM in Kigali, Rwanda, in July 2025.

What that document — and the research findings from our the Pan-African Catholic Theology and Pastoral Network, or PACTPAN, team of experts on polygamy that I lead, which includes the renowned African inculturation theologian professor Clement Chinkambako Abenguni Majawa — makes clear is that accompanying polygamous marriages in Africa is not a weakening of doctrine but a strengthening of pastoral method.

The insistence on seeking pastoral pathways by SECAM was the result of a worldwide synodal recognition, not of any ubiquity of polygamy in Africa, but that even if there is only one polygamous family in Africa, that family needs pastoral care — the Good Shepherd will leave 99 sheep to go after one who is lost.

The church must insist — clearly and consistently — that no new polygamous unions can be formed after baptism or catechumenal commitment. At the same time, it must accompany existing families responsibly so that they can fully participate in the life of the church as children of God rather than being treated as outcasts.

This approach reflects a long-standing Catholic principle: graduality in the journey, not in the law. Each polygamous situation has its own moral history — degrees of freedom, consent, coercion, and responsibility. Justice and mercy must be applied to persons, not categories.

A synodal opportunity: Women, children must come first

Any pastoral approach to polygamy must be judged by its impact on women and children. Forced dissolution of unions often leads to poverty, homelessness, interrupted education and social marginalization. A morally credible pastoral response must adopt a harm-reduction principle: no ecclesial decision should increase vulnerability.

This means prioritizing economic security, education, health care and protection from violence. It means recognizing that the Gospel's demand for justice is inseparable from its call to holiness.

Accompaniment must also be paired with prevention. Polygamy will not disappear through prohibition alone. The church must make monogamy realistically possible by addressing the pressures that undermine it — economic insecurity, infertility stigma, and extended-family expectations.

Marriage preparation must be culturally grounded and socially supported. Monogamy must be presented not merely as a rule, but as a path to dignity, reciprocity and shared flourishing.

Finally, the church should recognize that Africa requires pastoral flexibility — not because moral standards are lower, but because social realities are more complex. Continental guidelines, developed by African bishops and theologians, would enable faithful, yet contextually appropriate, pastoral care in communion with the universal church.

If the Gospel is truly good news, it must be capable of healing all God's people — especially those treated as outcasts in polygamous marriages — without caricature, without erasure, and without sacrificing the vulnerable on the altar of moral clarity.

This column first appeared at VoiceAfrique Catholic, a news outlet dedicated to providing in-depth analysis of stories and developments surrounding the extraordinary growth and impact of Catholicism in Africa. It is being republished with permission.